Surge in Syphilis Cases Leads Some Providers to Ration Penicillin

When Stephen Miller left his primary care practice to work in public health a little under two years ago, he said, he was shocked by how many cases of syphilis the clinic was treating.

For decades, rates of the sexually transmitted infection were low. But the Hamilton County Health Department in Chattanooga — a midsize city surrounded by national forests and nestled into the Appalachian foothills of Tennessee — was seeing several syphilis patients a day, Miller said. A nurse who had worked at the clinic for decades told Miller the wave of patients was a radical change from the norm.

What Miller observed in Chattanooga is reflective of a trend that is raising alarm bells for health departments across the country.

Nationwide, syphilis rates are at a 70-year high. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Jan. 30 that 207,255 cases were reported in 2022, continuing a steep increase over five years. Between 2018 and 2022, syphilis rates rose about 80%. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections — especially syphilis — is “out of control,” said the National Coalition of STD Directors.

The surge has been even more pronounced in Tennessee, where infection rates for the first two stages of syphilis grew 86% between 2017 and 2021.

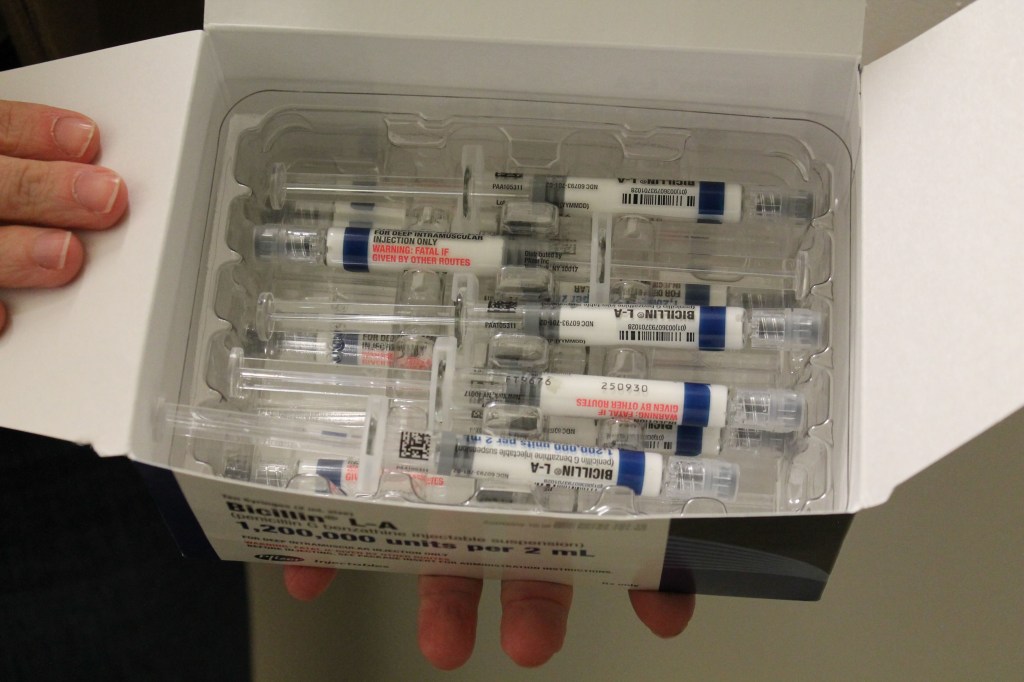

But this already difficult situation was complicated last spring by a shortage of a specific penicillin injection that is the go-to treatment for syphilis. The ongoing shortage is so severe that public health agencies have recommended that providers ration the drug — prioritizing pregnant patients, since it is the only syphilis treatment considered safe for them. Congenital syphilis, which happens when the mom spreads the disease to the fetus, can cause birth defects, miscarriages, and stillbirths.

Across the country, 3,755 cases of congenital syphilis were reported to the CDC in 2022 — that’s 10 times as high as the number a decade before, the recent data shows. Of those cases, 231 resulted in stillbirth and 51 led to infant death. The number of cases in babies swelled by 183% between 2018 and 2022.

“Lack of timely testing and adequate treatment during pregnancy contributed to 88% of cases of congenital syphilis,” said a report from the CDC released in November. “Testing and treatment gaps were present in the majority of cases across all races, ethnicities, and U.S. Census Bureau regions.”

Hamilton County’s syphilis rates have mirrored the national trend, with an increase in cases for all groups, including infants.

In November, the maternal and infant health advocacy organization March of Dimes released its annual report on states’ health outcomes. It found that, nationwide, about 15.5% of pregnant people received care beginning in the fifth month of pregnancy or later — or attended fewer than half the recommended prenatal visits. In Tennessee, the rate was even worse, 17.4%.

But Miller said even those who attend every recommended appointment can run into problems because providers are required to test for syphilis only at the beginning of a pregnancy. The idea is that if you test a few weeks before birth, there is time to treat the infection.

However, that recommendation hinges on whether the provider suspects the patient was exposed to the bacterium that causes syphilis, which may not be obvious for people who say their relationships are monogamous.

“What we found is, a lot of times their partner was not as monogamous, and they were bringing it into the relationship,” Miller said.

Even if the patient tested negative initially, they may have contracted syphilis later in pregnancy, when testing for the disease is not routine, he said.

Two antibiotics are used to treat syphilis, the injectable penicillin and an oral drug called doxycycline.

Patients allergic to penicillin are often prescribed the oral antibiotic. But the World Health Organization strongly advises pregnant patients to avoid doxycycline because it can cause severe bone and teeth deformities in the infant.

As a result, pregnant syphilis patients are often given penicillin, even when they’re allergic, using a technique called desensitization, said Mark Turrentine, a Houston OB-GYN. Patients are given low doses in a hospital setting to help their bodies get used to the drug and to check for a severe reaction. The penicillin shot is a one-and-done technique, unlike an antibiotic, which requires sticking to a two-week regimen.

“It’s tough to take a medication for a long period of time,” Turrentine said. The single injection can provide patients and their clinicians peace of mind. “If they don’t come back for whatever reason, you’re not worried about it,” he said.

The Metro Public Health Department in Nashville, Tennessee, began giving all nonpregnant adults with syphilis the oral antibiotic in July, said Laura Varnier, nursing and clinical director.

Turrentine said he started seeing advisories about the injectable penicillin shortage in April, around the time the antibiotic amoxicillin became difficult to find and physicians were using penicillin as a substitute, potentially precipitating the shortage, he said.

The rise in syphilis has created demand for the injection that manufacturer Pfizer can’t keep up with, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. “There is insufficient supply for usual ordering,” the ASHP said in a memo.

Even though penicillin has been around a long time, manufacturing it is difficult, largely because so many people are allergic, said Erin Fox, associate chief pharmacy officer for the University of Utah health system and an adjunct professor at the university, who studies drug shortages.

“That means you can’t make other drugs on that manufacturing line,” she said. Only major manufacturers like Pfizer have the resources to build and operate such a specialized, cordoned-off facility. “It’s not necessarily efficient — or necessarily profitable,” Fox said.

In a statement, Pfizer confirmed the amoxicillin shortage and surge in syphilis increased demand for injectable penicillin by about 70%. Representatives said the company invested $38 million in the facility that produces this form of penicillin, hiring more staff and expanding the production line.

“This ramp up will take some time to be felt in the market, as product cycle time is 3-6 months from when product is manufactured to when it is available to be released to customers,” the statement reads. The company estimated the shortage would be significantly alleviated by spring.

In the meantime, Miller said, his clinic in Chattanooga is continuing to strategize. Each dose of injectable penicillin can cost hundreds of dollars. Plus, it has to be placed in cold storage, and it expires after 48 months.

Even with the dramatic increase in cases, syphilis is still relatively rare. More than 7 million people live in Tennessee, and in 2019, providers statewide reported 683 cases of syphilis.

Health departments like Miller’s treat the bulk of syphilis patients. Many patients are sent by their provider to the health department, which works with contact tracers to identify and notify sexual partners who might be affected and tests patients for other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

“When you diagnose in the office, think of it as just seeing the tip of the iceberg,” Miller said. “You need a team of individuals to be able to explore and look at the rest of the iceberg.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes WPLN, NPR, and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 5 months ago

Pharmaceuticals, Public Health, Rural Health, States, CDC, Sexual Health, Tennessee

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Health Enters the Presidential Race

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

Based on the results of the first-in-the-nation primary in New Hampshire, it appears more likely than ever before that the 2024 presidential election will be a rerun of 2020: Joe Biden versus Donald Trump. And health is shaping up to be a key issue.

Trump is vowing — again — to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which is even more popular than it was when Republicans failed to muster the congressional votes to kill it in 2017. Biden is doubling down on support for contraception and abortion rights.

And both are expected to highlight efforts to rein in the cost of prescription drugs.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico, Anna Edney of Bloomberg News, and Jessie Hellmann of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Alice Miranda Ollstein

Politico

Anna Edney

Bloomberg

Jessie Hellmann

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- Trump had a strong showing in the New Hampshire GOP primary. But Biden may be gathering momentum himself from an unexpected source: Drug industry lawsuits challenging his administration’s Medicare price negotiation plan could draw attention to Biden’s efforts to combat rising prescription drug prices, a major pocketbook issue for many voters.

- Biden’s drug pricing efforts also include using the government’s so-called march-in rights on pharmaceuticals, which could allow the government to lower prices on certain drugs — it’s unclear which ones. Meanwhile, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont is calling on his committee to subpoena the CEOS of two drugmakers in the latest example of lawmakers summoning Big Pharma executives to the Hill to answer for high prices.

- More than a year after the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to an abortion, abortion opponents gathered in Washington, D.C., for the March for Life rally, looking now to continue to advance their priorities under a future conservative presidency.

- One avenue that abortion opponents are eying is the 19th-century Comstock Act, which could not only prohibit the mailing of abortion pills to patients, but also prevent them from being mailed to clinics and medical facilities. Considering the abortion pill is now used in more than half of abortions nationwide, it would amount to a fairly sweeping ban.

- And state legislators continue to push more restrictive abortion laws, targeting care for minors and rape exceptions in particular. The ongoing quest to winnow access to the procedure amid public reservations reflected in polling and ballot initiatives highlights that, for at least some abortion opponents, fetuses are framed as an oppressed minority whose rights should not be subject to a majority vote.

Also this week, Rovner interviews Sarah Somers, legal director of the National Health Law Program, about the potential effects on federal health programs if the Supreme Court overturns a 40-year-old precedent established in the case Chevron USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: Health Affairs’ “‘Housing First’ Increased Psychiatric Care Office Visits and Prescriptions While Reducing Emergency Visits,” by Devlin Hanson and Sarah Gillespie.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Stat’s “The White House Has a Pharmacy — And It Was a Mess, a New Investigation Found,” by Brittany Trang.

Anna Edney: The New Yorker’s “What Would It Mean for Scientists to Listen to Patients?” by Rachael Bedard.

Jessie Hellmann: North Carolina Health News’ “Congenital Syphilis — An Ancient Scourge — Claimed the Lives of Eight NC Babies Last Year,” by Jennifer Fernandez.

Also mentioned on this week’s podcast:

Stat’s “Pharma’s Attack on Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Might Benefit Biden,” by John Wilkerson.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Health Enters the Presidential Race

KFF Health News’ ‘What the Health?’Episode Title: Health Enters the Presidential RaceEpisode Number: 331Published: Jan. 25, 2024

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, Jan. 25, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast, and things might’ve changed by the time you hear this. So here we go. We are joined today via video conference by Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Good morning.

Rovner: Jessie Hellmann of CQ Roll Call.

Jessie Hellmann: Hi there.

Rovner: And Anna Edney of Bloomberg News.

Anna Edney: Hello.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have my interview with Sarah Somers of the National Health Law Program. She’s going to explain what’s at risk for health care if the Supreme Court overturns the Chevron doctrine, and if you don’t know what that is, you will. But first, this week’s news. We’re going to start this week with politics. To absolutely no one’s surprise, Donald Trump won the first-in-the-nation New Hampshire primary, and even though he wasn’t even on the ballot, because Democrats no longer count New Hampshire as first, President [Joe] Biden handily won a write-in campaign.

Since it seems very likely at this point that the November ballot will pit Trump versus Biden once again, I thought we’d look, briefly at least, at both of their health agendas for now. Trump has once again vowed to try and repeal the Affordable Care Act, which not only didn’t go well in 2017, we learned this week that the federal marketplace enrolled a record 21.3 million people for this year. In 2017, that number was 12.2 million. Not to mention there are now a half a dozen more states that have expanded Medicaid to low-income childless adults.

So with so many more millions of Americans getting coverage via Obamacare, even if Trump wants to repeal and replace it, is there any chance Republicans would go along, even if he wins back majorities in the House and the Senate? They have seemed rather unwilling to reopen this box of worms.

Edney: I mean, certainly, I think that currently they’re unwilling. I don’t want to pretend that I know what the next several months will hold until November, but even before they’re willing or not, what would the plan be? We never saw one, and I don’t anticipate there would be any sort of real plan, particularly if it’s the Trump White House itself having to put the plan together to repeal Obamacare.

Rovner: Yes. How many times did he promise that “we’ll have a plan in two weeks” throughout most of his administration? Alice, you were saying?

Ollstein: Yes. I think what we should be thinking about, too, is this can happen not through Congress. There’s a lot of President Trump could do theoretically through the executive branch, not to repeal Obamacare, but to undermine it and make it work worse. They could slash outreach funding, they could let the enhanced tax credit subsidies expire — they’re set to expire next year. That would also be on Congress. But a president who is opposed to it could have a role in that; they could slash call center assistance. They could do a lot. So I think we should be thinking not only about could a bill get through Congress, but also what could happen at all of the federal agencies.

Rovner: And we should point out that we know that he could do some of these things because he did them in his first term.

Ollstein: He did them the first time, and they had an impact. The uninsured rate went up for the first time under Trump’s first term, for the first time since Obamacare went into effect. So it can really make a difference.

Rovner: And then it obviously went down again. But that was partly because Congress added these extra subsidies and even the Republican Congress required people to stay on Medicaid during the pandemic. Well, I know elsewhere, like on abortion, Trump has been all over the place, both since he was in office and then since he left office. And then now, Alice, do we have any idea where he is on this whole very sensitive abortion issue?

Ollstein: He has been doing something very interesting recently, which is he’s sort of running the primary message and the general message at the same time. So we’re used to politicians saying one thing to a primary audience. These are the hard-core conservatives who turn out in primaries and they want to hear abortion is going to be restricted. And then the general audience — look at how all of these states have been voting — they don’t want to hear that. They want to hear a more moderate message and so Trump has been sort of giving both at once. He’s both taking credit for appointing the Supreme Court justices, who overturned Roe v. Wade. He has said that he is pro-life, blah, blah, blah. But he has also criticized the anti-abortion movement for going too far in his view. He criticized Ron DeSantis’ six-week ban for going too far. He has said that any restrictions need to have exemptions for rape and incest, which not everyone in the movement agrees with. A lot of people disagree with that in the anti-abortion movement. And so it has been all over the place.

But his campaign is in close contact with a lot of these groups and the groups are confident that he would do what they want. So I think that you have this interesting tension right now where he is saying multiple mixed messages.

Rovner: Which he always does, and which he seems to somehow get away with. And again, just like with the ACA, we know that all of these things that he could do just from the executive branch about reproductive health, because he did them when he was president the first time. Meanwhile, President Biden, in addition to taking a victory lap on the Affordable Care Act enrollment, is doubling down on abortion and contraception, which is pretty hard because, first, as executive, he doesn’t have a ton of power to expand abortion rights the way Trump would actually have a lot of power to contract them.

And, also, because as we know, Biden is personally uncomfortable with this issue. So Alice, how well is this going to work for the Biden administration?

Ollstein: So what was announced is mostly sort of reiterating what is already the law, saying we’re going to do more to educate people about it and crack down on people who are not following it. So this falls into a few different buckets. Part of it is Obamacare’s contraception mandate. There have been lots of investigations showing that a lot of insurers are denying coverage for contraceptives they should be covering or making patients jump through hoops. And so it’s not reaching the people it should be reaching. And so they’re trying to do more on that front.

And then, on the abortion front, this is mostly in this realm of abortions in medical emergencies. They’re trying to educate patients on “you can file this complaint if you are turned away.” Of course, I’m thinking of somebody experiencing a medical emergency and needing abortion and being turned away, and I don’t think “I’m going to file an EMTALA [Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act] complaint with the federal government and hope that they do something” is maybe the first thing on their mind. But the new executive order also includes education for providers and hospitals on their obligations.

This is also something a Trump administration could completely change. They could come in and say, “Forget that guidance. Here’s our guidance, which is no abortions in these circumstances.” So this is a really sensitive issue, but I think that the Biden campaign has seen how people have been voting over the last two years and feels that this is a really good message for them to do something on.

Rovner: Meanwhile, one issue both Republicans and Democrats are trying to campaign on is bringing down the cost of prescription drugs. Stat News has a story this week suggesting that all the lawsuits against the Medicare drug negotiation program could actually help Biden with voters because it shows he’s going after Big Pharma. Frankly, it could also tell voters that the Biden administration actually did something to challenge Big Pharma. Polls show most people have no idea, but Trump can point to lots of lawsuits over things he tried to do to Big Pharma.

Does one or the other of them have an advantage here, Anna? I mean, I know they’re going in different directions, but when you sort of boil it into campaign-speak, it’s going to sound pretty similar, right?

Edney: I think that that’s true, but one of the differences is, at least currently, what Biden’s done and doing some price negotiation through Medicare so far for 10 drugs under his administration is going forward. And you can name the drugs, name the prices, talk about it a little bit more specifically. What Trump ran up against was the lawsuits not falling in his favor. So he wanted more transparency as far as the drug companies having to say the price of their drugs in TV ads, and that wasn’t able to happen. And also reference pricing, so that the prices would be benchmarked to other countries. And certainly that never went forward either. And Trump really used the going after pharma hard in the last campaign, I would say, in 2016. And it worked in the beginning, and you would see the stock of these companies start going down the second he said pharmaceutical companies are getting away with murder or whatever big comment he was making. But it eventually lost any real effect because there didn’t seem to be plans to do anything drastic.

He talked about potentially doing negotiation, like is happening currently, but then that never came to fruition once he was in office. So I don’t know if that will come across to voters, but certainly the pharma industry doesn’t seem to be as afraid of Trump as what Biden’s doing right now.

Rovner: Jessie, I know Congress is still working on this PBM [pharmacy benefit managers] transparency, big bill. Are we getting any closer to anything? I think members of Congress would also like to run on being able to say they’ve done something about prescription drug prices.

Hellmann: I was just talking to [Sen.] Chuck Grassley [R-Iowa] about this because he is the “OG PBM hater.” And he was like, “Why is nothing happening?” He was just very frustrated. There are several bills that have passed House and Senate committees, and so I think, at this point, it’s just a matter of cobbling them all together, finding ways to pay for things. And since there’s also so many other health care things that people want to get done, it’s a matter of “Do we have enough money to pay for everything? What’s going to save money? What’s going to cost money?”

There’s also these health care transparency measures that Congress is looking at. There’s this site-neutral hospital payments thing that could be a money saver. So I think there’s just a lot going on in trying to figure out how it all fits together. But PBMs, I could definitely see them doing something this year.

Rovner: Sometimes, I mean, often it’s like you can’t get things onto the agenda. In this case, it sounds like there’s lots of things on the agenda, but they’re going to need to pay for all of them and they’re going to fight over the few places where they could presumably get some savings.

Edney: I was going to say, I saw that Grassley and some other senators wrote the Federal Trade Commission because they are due for a report on PBMs they’ve been working on for about a year and a half. And I think that the senators who want to go after PBMs are kind of looking for that sort of backup and that deep dive into the industry to make those statements about cost savings and what this would do for pharmaceutical prices.

Rovner: Well, to ratchet this up one more step, the Biden administration has proposed a framework for when march-in rights might be used. Is this the real deal or a threat to get pharma to back down on complaints about the Medicare price negotiations? Anna, why don’t you explain what march-in rights are?

Edney: March-in rights, which have never been used on a pharmaceutical company, were something that were put into law — I think it was around 1980 with the Bayh-Dole Act — and what it allows the government to do is say we invested a ton of money, either through giving money to university research or in the company itself, to do the very basic science that got us to this breakthrough that then the company took across the finish line to get a drug on the market. But usually, I think the main reason you might use it is because then the company does nothing with it.

Say they bought it up and it could be a competitor to one of their drugs, so they don’t use it. But it seems like it could also be used if the price is prohibitive, that it’s something that’s really needed, but Americans aren’t getting access to it. And so the government would be able to take that patent back and lower the price on the drug. But I haven’t heard a specific drug that they want to use this on. So I don’t know if they’re serious about using the march-in rights.

There is a request for information to find out how people feel about this, how it might affect the industry. The argument being that it could hamper the innovation, but we hear that a lot from the pharmaceutical industry as well. So unclear if that’s a true defense to not using march-in rights.

Rovner: Although march-in rights are a pretty big gun. There’s a reason they’ve never been used. I’ve seen them … lawmakers sometimes trot it out kind of as a cudgel, but I’ve never … the only time I think I saw them come close was after the anthrax scare, right after 9/11, when there was potentially a shortage of the important antibiotic needed for that. There was muttering about this, but then I think the drug company decided on its own to lower the price, which got us over that.

Well, yet another tack is being pursued by Sen. Bernie Sanders, chairman of the Senate Health Committee. He’s going to make the committee vote next week on whether to subpoena the CEOs of Johnson & Johnson and Merck to require them to “provide testimony about why their companies charge substantially higher prices for medicine in the U.S. compared to other countries.” Well, we all know the answer to that. Other countries have price controls and the U.S. does not. So is this a stunt or not? And is he even going to get the rest of the committee to go along with the subpoena?

Edney: This wouldn’t be the first hearing on high drug prices pulling in CEOs. And it’s so opaque that you never get an answer. You never get something … I mean, certainly, they’ll blame PBMs and talk about that, and the finger-pointing will go somewhere else, but you never have some aha insight moment. So when the CEOs are coming in, it does feel a bit more like a show. And Bernie Sanders, the ones he wants to subpoena are from companies that are suing the Biden administration.

So there’s talk about whether that’s sort of a bit of a revenge him for that as well. I don’t know what exactly he would expect to hear from them that would change policy or what legislation they’re trying to work out by having this hearing.

Rovner: For an issue that everybody cares about, high drug prices. It sure has been hard to figure out a way into it for politicians.

Ollstein: We have seen public shaming, even without legislation behind it, can have a difference. I think we’ve seen that on the insulin front. And so I think it’s not completely a fool’s errand here, what Bernie’s trying to do. It will be interesting to see if the rest of the committee goes along with it. There’s been some tensions on the committee. There’s been bipartisan support for some of his efforts, and then others — less on the health front, I think more on the labor front — you’ve had a lot of pushback from the Republican members, and so it’ll be very telling.

Rovner: I was actually in the room when the tobacco industry CEOs came to testify at the House Energy and Commerce Committee, and that was pretty dramatic, but I feel like that was a very different kind of atmosphere than this is. I know everybody’s been trying to repeat that moment for — what is it? — 25, 30 years now. It was in the early 1990s, and I don’t think anybody really successfully has, but they’re going to keep at it.

All right, well, let us turn to abortion. Last Saturday would have been the 51st anniversary of Roe v. Wade, and the day before was the annual March for Life, the giant annual anti-abortion demonstration that used to be a march to the Supreme Court to urge the justices to overrule Roe. Well, that mission has been accomplished. So now what are their priorities, Alice?

Ollstein: Lots of things. And a lot of the effort right now is going towards laying the groundwork, making plans for a potential second Trump administration or a future conservative president. They see not that much hope on the federal level for their efforts currently, with the current president and Congress, but they are trying to do the prep work for the future. They want a future president to roll back everything Biden has done to expand abortion access. That includes the policies for veterans and military service members. That includes wider access to abortion pills through the mail and dispensing at retail pharmacies, all of that.

So they want to scrap all of that, but they also want to go a lot further and are exploring ways to use a lot of different agencies and rules and bureaucratic methods and funding mechanisms to do this, because they’re not confident in passing a bill through Congress. We’ve seen Congress not able to do that even under one-party rule in either direction. And so they’re really looking at the courts, which are a lot more conservative than they were several years ago.

Rovner: Largely thanks to Trump.

Ollstein: Exactly, exactly. So the courts, the executive branch, and then, of course, more efforts at the state level, which I know we’re going to get into.

Rovner: We are. Before that, though, one of the things that keeps coming up in discussions about the anti-abortion agenda is something called the Comstock Act. We have talked about this before, although it’s been a while, but this is an 1873 law, which is still on the books, although largely unenforced, that banned the mailing of anything that could be used to aid in an abortion, among other things. Could an anti-abortion administration really use Comstock to basically outlaw abortion nationwide?

I mean, even things that are used for surgical abortion tend to come through … it’s not just the mail, it’s the mail or FedEx or UPS, common carrier.

Ollstein: Yes. So this is getting a lot more attention now and it is something anti-abortion groups are absolutely calling for, and people should know that this wouldn’t only prohibit the mailing of abortion pills to individual patients’ homes, which is increasingly happening now. This would prevent it from being mailed to clinics and medical facilities. The mail is the mail. And so because abortion medication is used in more than half of all abortions nationwide, it could be a fairly sweeping ban.

And so the Biden administration put out a memo from the Justice Department saying, “Our interpretation of the Comstock Act is that it does not prohibit the mailing of abortion pills.” The Trump administration or whoever could come in and say, “We disagree. Our interpretation is that it does.” Now, how they would actually enforce it is a big question. Are you going to search everyone’s mail in the country? Are you going to choose a couple of people and make an example out of them?

That’s what happened under the original Comstock Act. Back in the day, they went after a few high-profile abortion rights activists and made an example out of them. I think nailing them down on how it would be enforced is key here. And of course there would be tons of legal challenges and battles no matter what.

Rovner: Absolutely. Well, let us turn to the states. It’s January, which is kind of “unveil your bills” time in state legislatures, and they are piling up. In Tennessee, there’s a bill that would create a Class C felony, calling for up to 15 years in prison, for an adult who “recruits, harbors or transports a pregnant minor out of state for an abortion.” There’s a similar bill in Oklahoma, although violators there would only be subject to five years in prison.

Meanwhile, in Iowa, Republican lawmakers who are writing guidelines for how to implement that state’s six-week ban, which is not currently in effect, pending a court ruling, said that the rape exception could only be used if the rape is “prosecutable,” without defining that word. Are these state lawmakers just failing to read the room or do they think they are representing what their voters want?

Edney: I don’t really know. I think clearly there are a lot of right-wing Republicans who are elected to office and feel that they have a higher calling that doesn’t necessarily reflect what their constituents may or may not want, but more is that they know better. And I think that that could be some of this, because certainly the anti-abortion bills or movements have been rejected by voters in places you might not exactly expect it.

Rovner: It feels like we’re getting more and more really “out there” ideas on the anti-abortion side at the same time that we’re getting more and more ballot measures of voters in both parties wanting to protect abortion rights, at least to some extent.

Ollstein: And I think going off what Anna said, I think that anti-abortion leaders, including lawmakers, are being more upfront now, saying that they don’t believe that this should be something that the democratic process has a voice in. The framing they use is that fetuses are an oppressed minority and their rights should not be subject to a majority vote. That’s their framing, and they’re being very upfront saying that these kinds of ballot referendums shouldn’t be allowed, and that states that do allow them should get rid of that. We’ll see if that happens. There are obviously lots of attempts to thwart specific state efforts to put abortion on the ballot. There are lawsuits pending in Nevada and Florida. There are attempts to raise the signature threshold, raise the vote threshold, just make it harder to do overall. But I found it very interesting and a pretty recent development that folks are coming out and saying the quiet part out loud. Saying, “We don’t believe The People should be able to decide this.”

Rovner: Well, obviously not an issue that is going away anytime soon. All right, well that is this week’s news. Now we will play my interview with Sarah Somers, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am pleased to welcome to the podcast Sarah Somers, legal director of the National Health Law Program. She’s going to explain, in English hopefully, what’s at stake in the big case the Supreme Court heard earlier this month about herring fishing. Sarah, welcome to “What the Health?”

Sarah Somers: Thank you for having me, Julie. I’m glad to be here.

Rovner: So this case, and I know it’s actually two cases together, is really about much more than herring fishing, right? It seems to be about government regulation writ large.

Somers: That’s right. The particular issue in the case is about a national marine fisheries regulation that requires herring fishing companies to pay for observers who are on board — not exactly an issue that’s keeping everyone but herring fishermen up at night. And the fishing company challenged the rule, saying that it wasn’t a reasonable interpretation of the statute. But what they also asked the court to do was to overrule a Supreme Court case that requires courts to defer to reasonable agency interpretations of federal statutes. That’s what’s known as “Chevron deference.”

Rovner: And what is Chevron deference and why is it named after an oil company?

Somers: Why aren’t we talking about oil now? Yes, Chevron deference is the rule that says that courts have to defer to a reasonable agency interpretation of a federal statute. So, under Chevron, there’s supposed to be a two-step process when considering whether, say, a regulation is a reasonable interpretation. They say, “Does the statute speak directly to it?” So in this case, did the statute talk about whether you have to pay for observers on herring boats? It didn’t.

So the next question was, if it doesn’t speak directly to it or if it’s ambiguous or unclear, then the court should defer to a reasonable interpretation of that statute. And what’s reasonable depends on what the court determines are sort of the bounds of the statute, whether the agency had evidence before it that supported it, whether it showed the proper deliberation and expertise.

Rovner: One of the reasons that regulations are sometimes 200 pages long, right?

Somers: Exactly. And sometimes courts do say, “You know what? The statute spoke right to this. We don’t have to go any further. We know what Congress wanted.” Other times they take a step further. And the reason it’s called Chevron is it’s named after a case that was decided 40 years ago in 1984 during the Reagan administration, and it was Chevron Inc. USA v. the Natural Resources Defense Council. That case was about a regulation interpreting the Clean Air Act and about regulating air pollution.

Rovner: So, as you point out, you helped write one of the amicus briefs in the case about what overturning Chevron would mean for health care. It’s not just about herring fishing and Clean Air Act. Can you give us the CliffsNotes version of what it would mean for health care?

Somers: One of the purposes of our amicus brief was just to give another angle on this, because we were talking a lot about regulations in the context of air pollution, clean water, and the environment, but it touches so many other things, and this is just one aspect of it. So this brief, which we authored along with the American Cancer Society Action Network, and a Boston law firm called Anderson Kreiger, was signed by other health-oriented groups: the American Lung Association, American Heart Association, Campaign for Tobacco-Free [Kids], and then the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Public Health.

You get the picture. These are all groups that have a vested interest in programs of the Department and Health and Human Services. The brief talks about regulations promulgated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. I’m going to call them CMS for short when we’re talking. And CMS is responsible for regulating the vast and complex Medicare and Medicaid programs. And, as you know, Medicare and Medicaid cover more than half of the population and touch the lives of almost everyone, regulating hospitals, some aspects of insurance, some aspects of practice of medicine.

You can’t escape the consequences of problems with these programs. And so that’s why the agency … Congress specifically gave HHS and CMS the power to regulate all of the issues in its purview. So that already have the power, and so the question is whether they use it wisely. We are arguing in this brief that for 40 years it’s worked just fine. That Congress has set the outer limits and been content to let the agency determine the specifics of these programs to fill in the gaps, as one Supreme Court case said. And this has implications for how hospitals operate, how insurance programs operate, and whether they operate smoothly.

And in our brief, we’re not really arguing for or against a particular interpretation or either for or against what the agency says. It’s just a matter of stability and certainty. The agency has the expertise, has the time, has the resources, and has the duty to figure out what these particular terms and statutes mean and how the programs should work. Just two examples we gave in the brief of the kind of issues that the agency should be determining are: What’s the definition of geographic area in the Medicaid Act for the purpose of setting hospital wages?

If your listeners are still listening, I hope, because that is boring, arcane, hyper-technical, and courts don’t have the expertise, much less the time, to do that. And CMS does. Or another question in a different area, whether feeding activities in a nursing home regulated by Medicaid: Are those nursing or nursing related services? The court’s not going to know. The courts doesn’t have expertise or time. And again, that’s what CMS is for.

So not only is this something that you need these interpretations in these rules to have the programs operate smoothly and consistently, and that’s the first part that’s important. But the second part is that you need consistency across the country. As you know well, there are hospital systems that operate across multi-states. There are Medicaid managed-care plans operating across multi-states. All aspects of health care is nationalized. If you have hundreds of district courts and courts of appeals coming up with different interpretations of these terms, you’re going to have a lot of problems. It’s not going to operate smoothly. So I heard some of the justices arguing, “Well, Congress just needs to do its job.”

Congress has obstacles to doing even the big, mega issues that are before them, these kinds of arcane specific issues. They don’t have the time or again, the expertise. That’s why they said, “CMS, you go do this.”

Rovner: When they were writing the Affordable Care Act, there were so many times in that legislation where it says, “The secretary shall” or “The secretary may.” It’s like, we’re going to punt all this technical stuff to HHS and let them do what they will.

Somers: Exactly. You figure out what the definition of a preventive service is, that’s not something that we are going to do. And there are also questions raised about is this … these unelected agency personnel, well, agencies — they are political appointees, and they also serve at the pleasure of the head of the agency. So they’re accountable to the executive branch and indirectly to the voters. The courts, at this point, once they’re on the court and the federal courts, they’re not accountable to the voters anymore. And so this would be a big shift of power towards the courts, and that is what we argued would be antithetical to the system working well.

Rovner: What would be an example of something that could get hung up in the absence of Chevron?

Somers: I thought that Justice [Ketanji Brown] Jackson, during the argument, gave a really good example. Under the Food and Drug Administration’s power to regulate new drugs and determining what is an adequate and well-controlled investigation. The idea of courts, every single drug that’s challenged in every single forum, having to delve into what that means without deference to the agency would be just a recipe for chaos, really.

Rovner: So some people have argued that Chevron is already basically gone, as far as the Supreme Court is concerned, that it’s been replaced by the major questions doctrine, which is kind of what it sounds like. If a judge thinks a question is major, and they will assume that the Congress has not delegated it to the agency to interpret. So what difference would it make if the court formally overturned Chevron or not here? I guess what you’re getting at is that we’re more worried about the lower courts at this point than the Supreme Court, right?

Somers: That’s right. The Supreme Court has not cited Chevron in something like 15 years. And they talked about that in the argument, but it’s for the lower courts. The lower courts still follow it. It is still very commonly cited and gives them a lot of guidance not to have to decide these issues in the first instance. It’s true that the major questions doctrine — and there are other threats to the power of the administrative agencies, and we should all be concerned about them. But this one is really the grease that keeps the machine going and keeps these systems going. And throwing all that up in the air would make a big difference. If only because the question in all of these Chevron cases, and so many of them was not the ultimate issue — about whether the regulation was a good policy — but the question was, was the statute ambiguous or not? And so that’s the part that would be up in the air and everyone can go back and re-litigate these, including the big interests that have a lot of time and resources to devote to litigation. And that would cause a great deal of uncertainty, a lot of disruption, and a lot of problem for the courts and for all the entities that function under these systems.

Rovner: And that’s a really important point. It’s not just going forward. People who are unhappy with what a regulation said could go back, right?

Somers: Oh yeah. They could go back. They could go to different courts. We’ve seen how litigants can forum-shop. They can find a judge that they think is going to be sympathetic to their argument and make a determination that affects the whole country.

Rovner: Well, we will be watching. Sarah Somers, thanks so much for joining us.

Somers: My pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Rovner: We are back, and it’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s when we each recommend a story we read this week we think you should read, too. As always, don’t worry if you miss it. We will post the links on the podcast page at kffhealthnews.org and in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Jessie, you were the first to join in this week. Why don’t you tell us about your extra credit?

Hellmann: Yeah. Mine is from North Carolina Health News. They wrote about how congenital syphilis is killing babies in the state. They had eight cases of deaths last year — compared to a decade ago, they had one. So it’s something that’s been on the rise in North Carolina, but also nationwide, and it’s caused a lot of alarm among public health officials because it’s pretty preventable. It’s something that doesn’t need to happen, but the story is about what the state is doing to improve their outreach to pregnant people. They’re doing media campaigns, they’re trying to make sure that people are doing their prenatal care and just trying to stop this from happening. So I thought that was a good story. It’s definitely kind of an under-reported issue. It’s something that public health officials have been raising an alarm about for a while now, but there’s just not enough funding or attention on the issue.

Rovner: For all the arguing about abortion, there’s not been a lot of discussion about maternal and child health, which obviously appears to be the one place that both sides agree on. Anna.

Edney: Mine’s in The New Yorker by Rachael Bedard. It’s “What Would It Mean for Scientists to Listen to Patients?” And it’s interesting, it’s about two Yale researchers who are doing a long-covid study, but it’s unique in the sense that when the CDC or anyone else does a long-covid study, they typically are trying to say, “Here are the exact symptoms. We’re going to work with 12 of them.” Whereas we know long covid, it’s seemingly a much more expansive symptom list than that, but researchers really like to have kind of metrics to go by.

But what these Yale researchers are doing is letting all of that go and just letting anybody in this and talking to them. They’re holding monthly town halls with people who are in this, whoever wants to show up and come and just talk to them about what’s going on with them and trying to find out, obviously, what could help them. But they’re not giving medical advice during these, but just listening. And it just was so novel, and maybe it shouldn’t be, but I found it fascinating to read about and to get their reactions. And it’s not always easy for them. I mean, the patients get upset and want something to happen faster, but just that somebody is out there doing this research and including anybody who feels like they have long covid. It was really well-written too.

Rovner: It’s a really good story. Alice.

Ollstein: So I’m breaking my streak of extremely depressing, grim stories and sharing kind of a funny one, although it could have some serious implications. This is from Stat, and it’s from an inspector general report about how the White House pharmacy, which is run by basically the military, functioned under President Trump. And it functioned like sort of a frat house. There was no official medical personnel in charge of handing out the medications, and they were sort of handed out to whoever wanted them, including people who shouldn’t have been getting them. People were just rifling through bins of medications and taking what they wanted. These included pills like Ambien and Provigil, sort of uppers and downers in the common parlance. And so I think this kind of scrutiny on something that I didn’t even know existed. The White House pharmacy is pretty fascinating.

Rovner: It was a really, really interesting story. Well, I also have something relatively hopeful. My extra credit this week is a journal article from Health Affairs with the not-so-catchy headline “‘Housing First’ Increased Psychiatric Care Office Visits and Prescriptions While Reducing Emergency Visits,” by Devlin Hanson and Sarah Gillespie. And if they will forgive me, I would rename it, calling it maybe “Prioritizing Permanent Housing for Homeless People Provides Them a Better Quality of Life at Potentially Less Cost to the Public.”

It’s about a “Housing First” experiment in Denver, which found that the group that was given supportive housing was more likely to receive outpatient care and medications and less likely to end up in the emergency room. The results weren’t perfect. There was no difference in mortality between the groups that got supportive housing and the groups that didn’t. But it does add to the body of evidence about the use of so-called social determinants of health, and how medicine alone isn’t the answer to a lot of our social and public health ills.

OK. That is our show. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate it if you left us a review; that helps other people find us, too. Special thanks as always to our technical guru, Francis Ying, and our editor, Emmarie Huetteman. As always, you can email us your comments or questions. We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org, or you can still find me at X, @jrovner, or @julierovner at Bluesky or @julie.rovner at Threads. Anna, where are you these days?

Edney: Mostly just on Threads, so @anna_edneyreports.

Rovner: Alice?

Ollstein: @AliceOllstein.

Rovner: Jessie.

Hellmann: @jessiehellmann on Twitter.

Rovner: We will be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 6 months ago

Courts, Elections, Health Care Costs, Multimedia, Pharmaceuticals, Public Health, States, The Health Law, Abortion, Drug Costs, KFF Health News' 'What The Health?', New Hampshire, Podcasts, Women's Health

What the Health Care Sector Was Selling at the J.P. Morgan Confab

SAN FRANCISCO — Every year, thousands of bankers, venture capitalists, private equity investors, and other moneybags flock to San Francisco’s Union Square to pursue deals. Scores of security guards keep the homeless, the snoops, and the patent-stealers at bay, while the dealmakers pack into the cramped Westin St.

Francis hotel and its surrounds to meet with cash-hungry executives from biotech and other health care companies. After a few years of pandemic slack, the 2024 J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference regained its full vigor, drawing 8,304 attendees in early January to talk science, medicine, and, especially, money.

1. Artificial Intelligence: Revolutionary or Not?

Of the 624 companies that pitched at the four-day conference, the biggest overflow crowd may have belonged to Nvidia, which unlike the others isn’t a health care company. Nvidia makes the silicon chips whose computing power, when paired with ginormous catalogs of genes, proteins, chemical sequences, and other data, will “revolutionize” drug-making, according to Kimberly Powell, the company’s vice president of health care. Soon, she said, computers will customize drugs as “health care becomes a technology industry.” One might think that such advances could save money, but Powell’s emphasis was on their potential for wealth creation. “The world’s first trillion-dollar drug company is out there somewhere,” she dreamily opined.

Some health care systems are also hyping AI. The Mayo Clinic, for example, highlighted AI’s capacity to improve the accuracy of patient diagnoses. The nonprofit hospital system presented an electrocardiogram algorithm that can predict atrial fibrillation three months before an official diagnosis; another Mayo AI model can detect pancreatic cancer on scans earlier than a provider could, said Matthew Callstrom, chair of radiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

No one really knows how far — or where — AI will take health care, but Nvidia’s recently announced $100 million deal with Amgen, which has access to 500 million human genomes, made some conference attendees uneasy. If Big Pharma can discover its own drugs, “biotech will disappear,” said Sherif Hanala of Seqens, a contract drug manufacturing company, during a lunch-table chat with KFF Health News and others. Others shrugged off that notion. The first AI algorithms beat clinicians at analyzing radiological scans in 2014. But since that year, “I haven’t seen a single AI company partner with pharma and complete a phase I human clinical trial,” said Alex Zhavoronkov, founder and CEO of Insilico Medicine — one of the companies using AI to do drug development. “Biology is hard.”

2. Weight Loss Pill Profits and Doubts

With predictions of a $100 billion annual market for GLP-1 agonists, the new class of weight loss drugs, many investors were asking their favorite biotech entrepreneurs whether they had a new Ozempic or Mounjaro in the wings this year, Zhavoronkov noted. In response, he opened his parlays with investors by saying, “I have a very cool product that helps you lose weight and gain muscle.” Then he would hand the person a pair of Insilico Medicine-embossed bicycle racing gloves.

More conventional discussions about the GLP-1s focused on how insurance will cover the current $13,000 annual cost for the estimated 40% of Americans who are obese and might want to go on the drugs. Sarah Emond, president of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which calculates the cost and effectiveness of medical treatments, said that in the United Kingdom the National Health Service began paying in 2022 for obese patients to receive two years of semaglutide — something neither Medicare nor many insurers are covering in the U.S. even now.

But studies show people who go off the drugs typically regain two-thirds of what they lose, said Diana Thiara, medical director for the University of California-San Francisco weight management program. Recent research shows that the use of these drugs for three years reduces the risk of death, heart attack, and stroke in non-diabetic overweight patients. To do right by them, the U.S. health care system will have to reckon with the need for long-term use, she said. “I’ve never heard an insurer say, ‘After two years of treating this diabetes, I hope you’re finished,’” she said. “Is there a bias against those with obesity?”

3. Spotlight on Tax-Exempt Hospitals

Nonprofit hospitals showed off their investment appeal at the conference. Fifteen health systems representing major players across the country touted their value and the audience was intrigued: When headliners like the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic took the stage, chairs were filled, and late arrivals crowded in the back of the room.

These hospitals, which are supposed to provide community benefits in exchange for not paying taxes, were eager to demonstrate financial stability and showcase money-making mechanisms besides patient care — they call it “revenue diversification.” PowerPoints skimmed through recent operating losses and lingered on the hospital systems’ vast cash reserves, expansion plans, and for-profit partnerships to commercialize research discoveries.

At Mass General Brigham, such research has led to the development of 36 drugs currently in clinical trials, according to the hospital’s presentation. The Boston-based health system, which has $4 billion in committed research funding, said its findings have led to the formation of more than 300 companies in the past decade.

Hospital executives thanked existing bondholders and welcomed new investors.

“For those of you who hold our debt, taxable and tax-exempt, thank you,” John Mordach, chief financial officer of Jefferson Health, a health system in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. “For those who don’t, I think we’re a great, undervalued investment, and we get a great return.”

Other nonprofit hospitals talked up institutes to draw new patients and expand into lucrative territories. Sutter Health, based in California, said it plans to add 30 facilities in attractive markets across Northern California in the next three years. It expanded to the Central Coast in October after acquiring the Sansum Clinic.

4. Money From New — And Old — Treatments for Autoimmune Disease

Autoimmunity drugs, which earn the industry $200 billion globally each year, were another hot theme, with various companies talking up development programs aimed at using current cancer drug platforms to create remedies for conditions like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. AbbVie, which has led the sector with its $200 billion Humira, the world’s best-selling drug, had pride of place at the conference with a presentation in the hotel’s 10,000-square-foot Grand Ballroom.

President Robert Michael crowed about the company’s newer autoimmune drugs, Skyrizi and Rinvoq, and bragged that sales of two-decades-old Humira were going “better than anticipated.” Although nine biosimilar — essentially, generic — versions of the drug, adalimumab, entered the market last year, AbbVie expects to earn more than $7 billion on Humira this year since the “vast majority” of patients will remain on the market leader.

In its own presentation, biosimilar-maker Coherus BioSciences conceded that sales of Yusimry, its Humira knockoff listed at one-seventh the price of the original, would be flat until 2025, when Medicare changes take effect that could push health plans toward using cheaper drugs.

Biosimilars could save the U.S. health care system $100 billion a year, said Stefan Glombitza, CEO of Munich-based Formycon, another biosimilar-maker, but there are challenges since each biosimilar costs $150 million to $250 million to develop. Seeing nine companies enter the market to challenge Humira “was shocking,” he said. “I don’t think this will happen again.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 6 months ago

california, Health Industry, Pharmaceuticals, States, Health IT, Hospitals, Prescription Drugs

STAT+: Klobuchar urges drugmakers to remove patents FTC calls improper and inaccurate

Amid a push to crack down on patent abuse by the pharmaceutical industry, a key U.S. lawmaker is urging six large drug companies to remove dozens of patents that were identified by regulators as improperly or inaccurately listed with a federal registry.

In a series of letters sent on Thursday, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) demanded the companies explain why they have, so far, not responded to warnings issued two months ago by the Federal Trade Commission to remove more than 100 patents from the registry. The agency threatened the drug companies with litigation if they failed to comply.

The FTC had challenged a total of 10 companies over listings for patents on such medicines as asthma inhalers and epinephrine auto-injectors as part of an effort to mitigate actions that thwart competition. Among the companies to which the agency sent warnings are AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Mylan Specialty, Boehringer Ingelheim, and subsidiaries of GSK and Teva Pharmaceutical.

1 year 6 months ago

Pharma, Pharmalot, patents, Pharmaceuticals, STAT+

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': 2023 Is a Wrap

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

Even without covid dominating the headlines, 2023 was a busy year for health policy. The ever-rising cost of health care remained an issue plaguing patients and policymakers alike, while millions of Americans lost insurance coverage as states redetermined eligibility for their Medicaid programs in the wake of the public health emergency.

Meanwhile, women experiencing pregnancy complications continue to get caught up in the ongoing abortion debate, with both women and their doctors potentially facing prison time in some cases.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Rachel Cohrs of Stat, Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call, and Joanne Kenen of Johns Hopkins University and Politico Magazine.

Panelists

Rachel Cohrs

Stat News

Joanne Kenen

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- As the next election year fast approaches, the Biden administration is touting how much it has accomplished in health care. Whether the voting public is paying attention is a different story. Affordable Care Act enrollment has reached record levels due in part to expanded financial help available to pay premiums, and the administration is also pointing to its enforcement efforts to rein in high drug prices.

- The federal government is adding staff to go after “corporate greed” in health care, targeting in particular the fast-growing role of private equity. The complicated, opaque, and evolving nature of corporate ownership in the nation’s health system makes legislation and regulation a challenge. But increased interest and oversight could lead to a better understanding of the problems of and, eventually, remedies for a profit-focused system of health care.

- Concluding a year that saw many low-income Americans lose insurance coverage as states reviewed eligibility for everyone in the Medicaid program, there’s no shortage of access issues left to tackle. The Biden administration is urging states to take action to help millions of children regain coverage that was stripped from them.

- Also, many patients are all too familiar with the challenges of obtaining insurance approval for care. There is support in Congress to scrutinize and rein in the use of algorithms to deny care to Medicare Advantage patients based on broad comparisons rather than individual patient circumstances.

- And in abortion news, some conservative states are trying to block efforts to put abortion on the ballot next year — a tactic some used in the past against Medicaid expansion.

- This week in health misinformation is an ad from Florida’s All Family Pharmacy touting the benefits of ivermectin for treating covid-19. (Rigorous scientific studies have found that the antibacterial drug does not work against covid and should not be used for that purpose.)

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Jordan Rau about his joint KFF Health News-New York Times series “Dying Broke.”

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: Business Insider’s “‘I Feel Conned Into Keeping This Baby,’” by Bethany Dawson, Louise Ridley, and Sarah Posner.

Joanne Kenen: The Trace’s “Chicago Shooting Survivors, in Their Own Words,” by Justin Agrelo.

Rachel Cohrs: ProPublica’s “Doctors With Histories of Big Malpractice Settlements Work for Insurers, Deciding if They’ll Pay for Care,” by Patrick Rucker, The Capitol Forum; and David Armstrong and Doris Burke, ProPublica.

Sandhya Raman: Roll Call’s “Mississippi Community Workers Battle Maternal Mortality Crisis,” by Lauren Clason.

Also mentioned in this week’s episode:

- Stat News’ “Humana Used Algorithm in ‘Fraudulent Scheme’ to Deny Care to Medicare Advantage Patients, Lawsuit Alleges,” by Casey Ross and Bob Herman.

- USA Today’s “Cigna Denied a Lung Transplant for a Cancer Patient. Insurer Now Says That Was an Eerror.’ By Ken Alltucker.

- Politico’s “Conservatives Move to Keep Abortion off the 2024 Ballot,” by Alice Miranda Ollstein and Megan Messerly.

- The New York Times’ “Why Democracy Hasn’t Settled the Abortion Question,” by Kate Zernike.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: 2023 Is a Wrap

KFF Health News’ ‘What the Health?’Episode Title: 2023 Is a WrapEpisode Number: 327Published: Dec. 21, 2023

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, Dec. 21, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might’ve changed by the time you hear this, so here we go.

We are joined today via video conference by Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins University and Politico Magazine.

Joanne Kenen: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning.

Rovner: And Rachel Cohrs of Stat News.

Rachel Cohrs: Hi.

Rovner: Later in this episode, we’ll have my interview with KFF Health News’ Jordan Rau, co-author of a super scary series done with The New York Times about long-term care. It’s called “Dying Broke.” But first, this week’s news. I thought we would try something a little bit different this week. It just happened that most of this week’s news also illustrates themes that we’ve been following throughout the year. So we get a this-week update plus a little review of the last 12 months, since this is our last podcast of the year. I want to start with the theme of, “The Biden administration has gotten a ton of things done in health, but nobody seems to have noticed.”

We learned this week that, with a month still to go, Affordable Care Act plan sign-ups are already at historic highs, topping 15 million, thanks, at least in part, to extra premium subsidies that the administration helped get past this Congress and which Congress may or may not extend next year. The administration has also managed to score some wins in the battle against high drug prices, which is something that has eluded even previous Democratic administrations. Its latest effort is the unveiling of 48 prescription drugs officially on the naughty list — that’s my phrase, not theirs — for having raised their prices by more than inflation during the last quarter of this year, and whose manufacturers may now have to pay rebates. This is something in addition to the negotiations for the high-priced drugs, right, Rachel?

Cohrs: Yeah, this was just a routine announcement about the drugs that are expected to be charged rebates and drugmakers don’t have to pay immediately; I think they’re kind of pushing that a little further down the road, as to when they’ll actually invoice those rebates. But the announcement raised a question in my mind of — certainly they want to tout that they’re enforcing the law; that’s been a big theme of this year — but it brought up a question for me as to whether the law is working to deter price hikes if these companies are all doing it anyway, so just a thought.

Rovner: It is the first year.

Cohrs: It is. This started going into effect at the end of last year, so it’s been a little over a year, but this is assessed quarterly, so the list has grown as time has gone on. But just a thought. Certainly there’s time for things to play out differently, but that’s at least what we’ve seen so far.

Rovner: They could say, which they did this week, it’s like, Look, these are drugs because they raised the prices, they’re going to have to give back some of that money. At least in theory, they’re going to have to give back some of that money.

Cohrs: In Medicare.

Rovner: Right. In Medicare. Some of this is still in court though, right?

Cohrs: Yes. So I think at any moment, I think this has been a theme of this year and will be carrying into next year, that there are several lawsuits filed by drugmakers, by trade associations, that just have not been resolved yet, and I think some of the cases are close to being fully briefed. So we may see kind of initial court rulings as to whether the law as a whole is constitutional. It is worth noting that most of those lawsuits are solely challenging the negotiation piece of the law and not the inflation rebates, but this could fall apart at any moment. There could be a stay, and I expect that the first court ruling is not going to be the last. There’s going to be a long appeals process. Who knows how long it’s going to take, how high it will go, but I think there is just a lot of uncertainty around the law as a whole.

Rovner: So the administration gets to stand there and say, “We did something about drug prices,” and the drug companies get to stand there and say, “Not yet you didn’t.”

Cohrs: Exactly. Yes, and they can both be correct.

Rovner: That’s basically where we are.

Cohrs: Yes.

Rovner: That’s right. Well, meanwhile, in other news from this week and from this year, the Federal Trade Commission, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Health and Human Services are all adding staff to go after what Biden officials call “corporate greed” — that is their words — in health care. Apparently these new staffers are going to focus on private equity ownership of health care providers, something we have talked about a lot and so-called roll-ups, which we haven’t talked about as much. Somebody explain what a roll-up is please.

Kenen: Julie, why don’t you?

Rovner: OK. I guess I’m going to explain what a roll-up is. I finally learned what a roll-up is. When companies merge and they make a really big company, then the Federal Trade Commission gets to say, “Mmm, you may be too big, and that’s going to hurt trade.” What a roll-up is is when a big company goes and buys a bunch of little companies, so each one doesn’t make it too big, but together they become this enormous — either a hospital system or a nursing home system or something that, again, is not necessarily going to make free trade and price limits by trade happen. So this is something that we have been seeing all year. Can the government really do anything about this? This also feels like sort of a lot of, in theory, they can do these things and in practice it’s really hard.

Cohrs: I feel like what we’ve seen in this space — I think my colleague Brittany wrote about kind of this move — is that the corporate structures around these entities are so complicated. Is it going to discourage companies from doing anything by hiring a couple people? Probably not. But I think the people power behind understanding how these structures work can lay the groundwork for future steps on understanding the landscape, understanding the tactics, and what we see, at least on the congressional side, is that a lot of times Congress is working 10 years behind some of the tactics that these companies are using to build market power and influence prices. So I think the more people power, the better, in terms of understanding what the most current tactics are, but it doesn’t seem like this will have significant immediate difference on these practices.

Kenen: I think that the gap between where the government is and where the industry is is so enormous. I think the role of PE [private equity] in health care has grown so fast in a relatively short period of time. Was there a presence before? Yes, but it’s just really taken off. So I think that if those who advocate for greater oversight, if they could just get some transparency, that would be their win, at the moment. They cannot go in and stop private equity. They would like to get to the point where they could curb abuse or set parameters or however you want to phrase it, and different people would phrase it in different ways, but right now they don’t even really know what’s going on. So, even among the Democrats, there was a fight this year about whether to include transparency language between [the House committees on] Energy and Commerce and Ways and Means, and I don’t think that was ever resolved.

I think that’s part of the “Let’s do it in January” mess. But I think they just sort of want not only greater insight for the government, but also for the public: What is going on here and what are its implications? People who criticize private equity — the defenders can always find some examples of companies that are doing good things. They exist. We all know who the two or three companies we hear all the time are, but I think it’s a really enormous black box, and not only is it a black box, but it’s a black box that’s both growing and shifting, and getting into areas that we didn’t anticipate a few years ago, like ophthalmology. We’ve seen some of these studies this year about specialties that we didn’t think of as PE targets. So it’s a big catch-up for roll-up.

Rovner: Yeah, and I think it’s also another place that the administration — and I think the Trump administration tried to do this too. Republicans don’t love some of these things either. The public complains about high health care costs. They’re right; we have ridiculously high health care costs in this country, much higher than in other countries, and this is one of the reasons why, is that there are companies going in who are looking to simply do it to make a profit and they can go in and buy these things up and raise prices. That’s a lot of what we’re seeing and a lot of why people are so frustrated. I think at very least it at least shows them: It’s like, “See, this is what’s happening, and this is one of the reasons why you’re paying so much.”

Kenen: It’s also changing how providers and practitioners work, and how much autonomy they have and who they work for. It’s in an era when we have workforce shortages in some sectors and burnout and dissatisfaction. There are pockets at least, and again, we don’t really know how big, because we don’t have our arms around this, but there are pockets; at least we do know where the PE ownership and how they dictate practice is worsening these issues of burnout and dissatisfaction. I’m having dinner tomorrow night with a expert on health care antitrust, so if we were doing this next week, I would be so much smarter.

Rovner: We will be sure to call on you in January. Workforce burnout: This is another theme that we’ve talked about a lot this year.

Kenen: It’s getting into places you just wouldn’t think. I was talking to a physical therapist the other day and her firm has been bought up, and it’s changing the way she practices and her ability to make decisions and how often she’s allowed to see a patient.

Rovner: Yeah. Well, another continuing theme. Well, yet another big issue this year has been the so-called Medicaid unwinding, as states redetermine eligibility for the first time since the pandemic began. All year, we’ve been hearing stories about people who are still eligible being dropped from the rolls, either mistakenly or because they failed to file paperwork they may never have received. Among the more common mistakes that states are making is cutting off children’s coverage because their parents are no longer eligible, even though children are eligible for coverage up to much higher family incomes than their parents. So even if the parents aren’t eligible anymore, the children most likely are.

This week, the federal government reached out to the nine states that have the highest rates of discontinuing children’s coverage, including some pretty big states, like Texas and Florida, urging them to use shortcuts that could get those children’s insurance back. But this has been a push-and-pull effort all year between the states and the federal government, with the feds trying not to push too hard. At one point, they wouldn’t even tell us which states they were sort of chiding for taking too many people off too fast. And it feels like some of the states don’t really want to have all these people on Medicaid and they would just as soon drop them even if they might be eligible. Is that kind of where we are?