Readers Weigh In on Abortion and Ways To Tackle the Opioid Crisis

Letters to the Editor is a periodic feature. We welcome all comments and will publish a selection. We edit for length and clarity and require full names.

Debunking Abortion Myths

Letters to the Editor is a periodic feature. We welcome all comments and will publish a selection. We edit for length and clarity and require full names.

Debunking Abortion Myths

I want to send a big THANK YOU to Matt Volz for writing a fact-checking article on the nonsense rhetoric around “abortion up until and after birth” that has run wild and unchallenged in the media (“GOP’s Tim Sheehy Revives Discredited Abortion Claims in Pivotal Senate Race,” July 9). Thanks for putting abortion later in pregnancy in context and debunking false assumptions.

I am a near-third-trimester abortion patient (nonviable pregnancy, terminated at 26 weeks), and I am so sick of hearing politicians like Tim Sheehy talk about something they have never experienced or bothered to learn about. It is as though I am watching the entire nation maliciously gossip about me and other parents like me. Those of us in the termination for medical reasons (TFMR) community have walked through hell only to have our voices, at best, be ignored or, more commonly, be insulted and threatened.

And I imagine watching this political circus is just as hurtful for parents who lost an infant shortly after birth and had to provide palliative care. That is who they are talking about with “abortion after birth”; they are talking about comfort care for infants who will not survive.

Thank you again for bringing a dose of reality to a conversation that never should have become political. These are impossible decisions that only parents should make. It was really refreshing to read Volz’s article and know that some journalists are still willing to fact-check the absurd claims floating around. It was encouraging to know that someone does see us.

— Anne Angus, Bozeman, Montana

A physician and Yale professor of radiology and biomedical imaging took to the social platform X to share feedback:

.@SenatorTester is a great Senator. And his opponent is a great liar. Both the GOP presidential candidate and Tim Sheehy have perpetuated this lie. Please push back every time you hear it. https://t.co/1LBGPgOA2u

— (((Howard Forman))) (@thehowie) July 9, 2024

— Howard Forman, New Haven, Connecticut

I just read your article at PolitiFact on Republican Senate candidate Tim Sheehy’s statement about abortion, and I would like to point out (what I believe) are a couple of errors.

1. In paragraph 10, you quote KFF’s Alina Salganicoff saying that “in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating health care provider, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant patient’s life or health.” Now, you may know that almost at the same time that the Roe v. Wade decision was released, there was a decision called Doe v. Bolton that interpreted “health” to mean almost anything. That broad interpretation of health is found in your article in paragraph 24: “Women have abortions later in pregnancy either because they find out new information or because of economic or political barriers,” [Katrina] Kimport said.

When a woman can have an abortion after viability because she offers any reason that can be interpreted as “health,” then abortion would be legal throughout all nine months of pregnancy. I believe that you are wrong in your interpretation. Democrats do not want to name any restriction on abortion during all nine months, and every mention of “health” is a fig leaf that does not restrict abortion at all. Every abortion advocate knows that.

2. Whether late-term abortions are rare or not is logically irrelevant to whether late-term abortions should be restricted.

Why don’t you know these things?

— Darryl A. Linde, Tahlequah, Oklahoma

An Air Force veteran added his two cents on X:

Dems have the facts. Republicans spread fear and lies.https://t.co/6CWfKhqxJZ

— James Knight (@jamesUSAF_vet) July 12, 2024

— James Knight, Reno, Nevada

Making a Healthy Difference for the Homeless

Thank you for printing this story (“A California Medical Group Treats Only Homeless Patients — And Makes Money Doing It,” July 19). It really piqued my interest and portrayed a positive solution for getting care to the people.

Up here in the Bay Area, I believe there are a couple of groups who go out and find what needs doing instead of waiting for people to come to them — but nothing like this. Makes me curious about what we actually have going on here.

— Laurie Lippe, El Cerrito, California

A self-described “nurse turned health tech nerd” commended the effort on X:

"They distribute GPS devices so they can track their homeless patients. They keep company credit cards on hand in case a patient needs emergency food or water, or an Uber ride to the doctor"This is healthcare at its best 💕https://t.co/UhM1dgTPH7

— Rik Renard (@rikrenard) July 22, 2024

— Rik Renard, New York City

A senior policy director at the National Health Care for the Homeless Council shared the post on X — while stressing that her tweets reflected her own opinions and not those of her organization:

I’m with @DrJimWithers: “I do worry about the corporatization of street medicine and capitalism invading what we’ve been building, largely as a social justice mission outside of the traditional health care system.” https://t.co/IOjazvrvqP

— Barbara DiPietro (@BarbaraDiPietro) July 19, 2024

— Barbara DiPietro, Baltimore

On X, a physician who says she champions “physicians, patients, public health, and the patient-physician relationship” reacted to our coverage surrounding the Federal Trade Commission’s rule banning the use of noncompete agreements in employment contracts:

FTC #noncompete crackdown may not protect doctors and nurses at ~64% of US community hospitals that are tax-exempt nonprofits or government-owned.But, @FTC said some nonprofits could be bound by the rule if they do not operate as true charities. https://t.co/9fDbfVflTH

— Marilyn Heine (@MarilynHeineMD) May 28, 2024

— Marilyn Heine, Langhorne, Pennsylvania

Without a Noncompete Ban on All Employers, Rural Access to Care Suffers

When news broke that the Federal Trade Commission would be banning noncompete agreements in employment contracts, many of us in the medical profession celebrated. However, until nonprofit hospitals and health care facilities benefit from the same ban, access to care — particularly in rural regions — will suffer.

As reported in “Health Worker for a Nonprofit? The New Ban on Noncompete Contracts May Not Help You” (June 5), about two-thirds of U.S. community hospitals are nonprofit or government-owned. This means that most hospitals nationwide may continue to enforce noncompete agreements among their employees, a practice that will have an outsize impact on rural medical professionals.

As a rheumatologist in a rural area, I’ve seen how detrimental limited access to care is for patients. Noncompete agreements serve only to further limit access to much-needed care. Due to the physician shortage being particularly acute in rural America, there are oftentimes only a few specialty physicians servicing a large region. Suppose one of these specialists is employed by a large health system and wants to transition to a private practice. It reduces the number of accessible specialists in the area when their noncompete agreement prohibits them from practicing near any of the health care facilities associated with the system. And increasing consolidation across health care means many rural regions may have only a single health system that operates across the entire state and surrounding areas. A geographically limiting noncompete agreement essentially stops a physician or medical professional from practicing entirely in the area, or they must uproot their life and move away from the major health system.

I hope the FTC takes further action to include nonprofit health care employers in its noncompete ban. I also urge nonprofit employers to consider their rural patients’ access to care when requiring providers to sign noncompete agreements. It’s in the best interest of our patient’s health to get rid of these agreements entirely.

— Chris Phillips, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, Paducah, Kentucky

The president of the Texas Medical Board also posted on X with feedback:

Is it a coincidence that this affects everyone, except those who work for nonprofit hospitals and health care facilities, which employs the largest number of medical professionals?The FTC and it's selective enforcement and rules is blatantly obvious! https://t.co/RzXInqiJ8D

— Sherif Zaafran, MD (@szaafran) June 16, 2024

— Sherif Zaafran, Houston

Repurposing Newspaper Boxes for Public Health

I recently read your article by Mara Silvers regarding the state’s intended use of public health vending machines (PHVMs) to help fight the opioid overdose epidemic (“Montana’s Plan To Curb Opioid Overdoses Includes Vending Machines,” July 18). Working on the covid-19 response for almost four years now, and with our American Rescue Plan Act funding coming to an end, we recently used a byline in our equipment budget to purchase and place “resource kiosks” in the community.

In 2022, after researching the use of vending machines for test distribution, we discovered vending machines have high barrier-to-entry costs and high maintenance costs. And even if purchasing isn’t possible, rental contracts come with high fees. We decided it was better to use a lower-cost resource that could be purchased in greater quantity, easily placed with community partners, and required no maintenance: the refurbished newspaper kiosk.

We decided to purchase double-decker boxes, which have a secondary door, creating another shelf, for roughly $410 apiece and stocked them with covid tests, nasal naloxone, injectable naloxone, fentanyl test strips, xylazine test strips, various types of condoms, and lubrication packets. We are in the process of securing a supply of gun locks and adding links to our pilot landing page for individual free gun lock deliveries, as well as links for free sexually transmitted infection test kits. We have investigated providing dental supplies and other items, but long-term funding is a constant concern. Grant money for most programs (likely all ARPA dollars) is running out, so the viability of these types of pilot programs is tentative without a buy-in from state or federal agencies.

Mara’s article hinted at criteria for possible placements and, similarly, we didn’t use locational overdose data, which can be “othering” to communities, but instead placed these kiosks with community partners that have been accomplished supporters of their at-risk populations throughout the covid response. Each community partner helped protect the communities they served through increased access to resources and provided information as trusted messengers. Truly meeting people where they are.

While money quickly appeared to fight the covid pandemic, and states spirited away dollars for pet projects, that sea of funding has dried up, and there doesn’t seem to be a plan for any continued funding. Covid-related functions have all been folded back into communicable disease epidemiology programs, which were already underfunded; in our state, the money funding the naloxone bulk fund is also drying up. Covid deaths might be down, but there is always a new bug (H5N1), STI infections are up, and gun-related deaths grow year over year. Funding population-level health interventions is our next pandemic.

With enough funding, kiosk-sized PHVMs could be swiftly added to any public health agency’s or community program’s quiver of tools to help increase access to resources and information for the most vulnerable residents.

Thank you for publishing a great article about the emerging opportunities to respond to changing public health needs!

— Christopher Howk, Arapahoe County Public Health’s covid-19 testing and logistics coordinator, Greenwood Village, Colorado

A retiree with a PhD in quantum chemistry tweeted his surprise over the news:

Montana’s Plan To Curb Opioid Overdoses Includes Vending Machineshttps://t.co/kNxYjnIOEO(What???!! Vending machines for opioids?)

— John Lounsbury (@jlounsbury59) July 18, 2024

— John Lounsbury, Lake Frederick, Virginia

Misappropriation of Opioid Settlement Funds

OK, so I see how all these states got all these lump sums of money for people like us who became addicted and whose lives were devastated by Purdue Pharma, Vicodin, and all the pharmacies (“Lifesaving Drugs and Police Projects Mark First Use of Opioid Settlement Cash in California,” July 12). How come all these states got all the money but those of us who have suffered have to wait, hire lawyers, and wait years for the money that was just handed over to these states? We’re the ones whose lives were devastated. My son was hooked, I was hooked, and my wife, and yet we must sit here penniless after the addiction, while all these states take the money — and they don’t do what they’re supposed to with it, and everyone knows it.

— Michael Stewart, Des Moines, Iowa

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 1 month ago

Health Industry, Public Health, Rural Health, Abortion, Homeless, Letter To The Editor, Misinformation, Opioids, Substance Misuse, Women's Health

Care Gaps Grow as OB/GYNs Flee Idaho

Not so long ago, Bonner General Health, the hospital in Sandpoint, Idaho, had four OB/GYNs on staff, who treated patients from multiple rural counties.

Not so long ago, Bonner General Health, the hospital in Sandpoint, Idaho, had four OB/GYNs on staff, who treated patients from multiple rural counties.

That was before Idaho’s near-total abortion ban went into effect almost two years ago, criminalizing most abortions. All four of Bonner’s OB/GYNs left by last summer, some citing fears that the state’s ban exposed them to legal peril for doing their jobs.

The exodus forced Bonner General to shutter its labor and delivery unit and sent patients scrambling to seek new providers more than 40 miles away in Coeur d’Alene or Post Falls, or across the state border to Spokane, Wash. It has made Sandpoint a “double desert,” meaning it lacks access to both maternity care and abortion services.

One patient, Jonell Anderson, was referred to an OB-GYN in Coeur d’Alene, roughly an hour’s drive from Sandpoint, after an ultrasound showed a mass growing in her uterus. Anderson made multiple trips to the out-of-town provider. Previously, she would have found that care close to home.

The experience isn’t limited to this small Idaho town.

A 2023 analysis by ABC News and Boston Children’s Hospital found that more than 1.7 million women of reproductive age in the United States live in a “double desert.” About 3.7 million women live in counties with no access to abortion and little to no maternity care.

Texas, Mississippi and Kentucky have the highest numbers of women of reproductive age living in double deserts, according to the analysis.

Amelia Huntsberger, one of the OB/GYNs who chose to leave Sandpoint — despite having practiced there for a decade — did so because she felt she couldn’t provide the care her patients needed under a law as strict as Idaho’s.

The growing provider shortages in rural states affect not only pregnant and postpartum women, but all women, said Usha Ranji, an associate director for Women’s Health Policy at KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

“Pregnancy is obviously a very intense period of focus, but people need access to this care before, during and after, and outside of pregnancy,” Ranji said.

The problem is expected to worsen.

In Idaho, the number of applicants to fill spots left by departing doctors has “absolutely plummeted,” said Susie Keller, CEO of the Idaho Medical Association.

“We are witnessing the dismantling of our health system,” she said.

This article is not available for syndication due to republishing restrictions. If you have questions about the availability of this or other content for republication, please contact NewsWeb@kff.org.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 1 month ago

Public Health, States, Abortion, Health Brief, Idaho, Rural Health, Women's Health

La gripe aviar es mala para las aves de corral y las vacas lecheras. No es una amenaza grave para la mayoría de nosotros… por ahora

Los titulares explotaron después que el Departamento de Agricultura confirmara que el virus de la gripe aviar H5N1 ha infectado a vacas lecheras en todo el país.

Las pruebas han detectado el virus en el ganado en nueve estados, principalmente en Texas y Nuevo México, y más recientemente en Colorado, dijo Nirav Shah, director principal adjunto de los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC), en un evento del 1 de mayo.

Otros animales, y al menos una persona en Texas, también se infectaron con el H5N1. Pero lo que más temen los científicos es si el virus se propagara de manera eficiente de persona a persona. Eso no ha sucedido y podría no suceder. Shah dijo que los CDC consideran que el brote de H5N1 “es un riesgo bajo para el público en general en este momento”.

Los virus evolucionan y los brotes pueden cambiar rápidamente. “Como con cualquier brote importante, esto se mueve a la velocidad de un tren bala”, dijo Shah. “De lo que hablamos ahora es de un instantánea de ese tren que se mueve rápidamente”. Lo que quiere decir es que lo que hoy se sabe sobre la gripe aviar H5N1 seguramente cambiará.

Con eso en mente, KFF Health News explica lo que se necesita saber ahora.

¿Quién contrae el virus que causa la gripe aviar?

Principalmente las aves. Sin embargo, en los últimos años, el virus de la gripe aviar H5N1 ha estado saltando cada vez más de las aves a los mamíferos en todo el mundo. La creciente lista, de más de 50 especies, incluye focas, cabras, zorrinos, gatos y perros salvajes en un zoológico en el Reino Unido. Al menos 24,000 leones marinos murieron en brotes de gripe aviar H5N1 en Sudamérica el año pasado.

Lo que hace que el brote actual en el ganado sea inusual es que se está propagando rápidamente de vaca a vaca, mientras que los otros casos, excepto las infecciones de leones marinos, parecen limitados. Los investigadores saben esto porque las secuencias genéticas de los virus H5N1 extraídos de las vacas este año eran casi idénticas entre sí.

El brote de ganado también preocupa porque agarró al país desprevenido. Los investigadores que examinan los genomas del virus sugieren que originalmente se transmitió de las aves a las vacas a finales del año pasado en Texas, y desde entonces se ha propagado entre muchas más vacas de las que se han examinado.

“Nuestros análisis muestran que esto ha estado circulando en vacas durante unos cuatro meses, bajo nuestras narices”, dijo Michael Worobey, biólogo especializado en evolución de la Universidad de Arizona en Tucson.

¿Es este el comienzo de la próxima pandemia?

Aún no. Pero es algo que vale la pena considerar porque una pandemia de gripe aviar sería una pesadilla. Más de la mitad de las personas infectadas por cepas anteriores del virus de la gripe aviar H5N1 de 2003 a 2016 murieron.

Incluso si las tasas de mortalidad resultan ser menos severas para la cepa H5N1 que circula actualmente en el ganado, las repercusiones podrían implicar muchas personas enfermas y hospitales demasiado abrumados para manejar otras emergencias médicas.

Aunque al menos una persona se infectó con el H5N1 este año, el virus no puede provocar una pandemia en su estado actual.

Para alcanzar este horrible estatus, un patógeno necesita enfermar a muchas personas en varios continentes. Y para lograrlo, el virus H5N1 necesitaría infectar a toneladas de personas. Eso no sucederá a través de saltos ocasionales del virus de los animales de granja a las personas. Más bien, el virus debe adquirir mutaciones para propagarse de persona a persona, como la gripe estacional, como una infección respiratoria transmitida principalmente por el aire cuando las personas tosen, estornudan y respiran.

Como aprendimos de covid-19, los virus transmitidos por el aire son difíciles de frenar.

Eso aún no ha sucedido. Sin embargo, los virus H5N1 ahora tienen muchas oportunidades para evolucionar a medida que se replican dentro de los organismos de miles de vacas. Como todos los virus, mutan a medida que se replican, y las mutaciones que mejoran la supervivencia del virus se transmiten a la próxima generación. Y debido a que las vacas son mamíferos, los virus podrían estar mejorando en reproducirse dentro de células más cercanas a las nuestras que las de las aves.

La evolución de un virus de gripe aviar listo para una pandemia podría facilitarse por una especie de superpoder que poseen muchos virus. Es decir, a veces intercambian sus genes con otras cepas en un proceso llamado recombinación.

En un estudio publicado en 2009, Worobey y otros investigadores rastrearon el origen de la pandemia del virus de la gripe porcina H1N1 en eventos en los que diferentes virus que causaban esta gripe, la gripe aviar y la gripe humana mezclaban y combinaban sus genes dentro de cerdos que se estaban infectando simultáneamente. Los cerdos no necesitan estar involucrados esta vez, advirtió Worobey.

¿Comenzará una pandemia si una persona bebe leche contaminada con el virus?

Aún no. La leche de vaca, así como la leche en polvo y la fórmula infantil, que se venden en tiendas se consideran seguras porque la ley requiere que toda la leche vendida comercialmente sea pasteurizada. Este proceso de calentar la leche a altas temperaturas mata bacterias, virus y otros microorganismos.

Las pruebas han identificado fragmentos de virus H5N1 en la leche comercial, pero confirman que los fragmentos del virus están muertos y, por lo tanto, son inofensivos.

Sin embargo, la leche “cruda” no pasteurizada ha demostrado contener virus H5N1 vivos, por eso la Administración de Drogas y Alimentos (FDA) y otras autoridades sanitarias recomiendan firmemente a las personas que no la tomen, porque podrían enfermarse de gravedad o algo peor.

Pero, aún así, es poco probable que se desate una pandemia porque el virus, en su forma actual, no se propaga eficientemente de persona a persona, como lo hace, por ejemplo, la gripe estacional.

¿Qué se debe hacer?

¡Mucho! Debido a la falta de vigilancia, el Departamento de Agricultura (USDA) y otras agencias han permitido que la gripe aviar H5N1 se propague en el ganado, sin ser detectada. Para hacerse cargo de la situación, el USDA recientemente ordenó que se sometan a pruebas a todas las vacas lecheras en lactancia antes que los ganaderos las trasladen a otros estados, y que se informen los resultados de las pruebas.

Pero al igual que restringir las pruebas de covid a los viajeros internacionales a principios de 2020 permitió que el coronavirus se propagara sin ser detectado, testear solo a las vacas que se mueven entre estados dejaría pasar muchos casos.

Estas pruebas limitadas no revelarán cómo se está propagando el virus entre el ganado, información que los ganaderos necesitan desesperadamente para frenarlo. Una hipótesis principal es que los virus se están transfiriendo de una vaca a la siguiente a través de las máquinas utilizadas para ordeñarlas.

Para aumentar las pruebas, Fred Gingrich, director ejecutivo de la American Association of Bovine Practitioners, dijo que el gobierno debería ofrecer fondos a los ganaderos para que informen casos y así tengan un incentivo para hacer pruebas. De lo contrario, dijo, informar solo daña la reputación por encima de las pérdidas financieras.

“Estos brotes tienen un impacto económico significativo”, dijo Gingrich. “Los ganaderos pierden aproximadamente el 20% de su producción de leche en un brote porque los animales dejan de comer, producen menos leche, y parte de esa leche es anormal y no se puede vender”.

Gingrich agregó que el gobierno ha hecho gratuitas las pruebas de H5N1 para los ganaderos, pero no han presupuestado dinero para los veterinarios que deben tomar muestras de las vacas, transportar las muestras y presentar los documentos. “Las pruebas son la parte menos costosa”, explicó.

Si las pruebas en las granjas siguen siendo esquivas, los virólogos aún pueden aprender mucho analizando secuencias genómicas del virus H5N1 de muestras de ganado. Las diferencias entre las secuencias cuentan una historia sobre dónde y cuándo comenzó el brote actual, el camino que recorre y si los virus están adquiriendo mutaciones que representan una amenaza para las personas.

Sin embargo, esta investigación vital se ha visto obstaculizada porque el USDA publica los datos incompletos y con cuentagotas, dijo Worobey.

El gobierno también debería ayudar a los criadores de aves de corral a prevenir brotes de H5N1, ya que estos matan a muchas aves y representan una amenaza constante de potenciales saltos de especies, dijo Maurice Pitesky, especialista en enfermedades de aves de la Universidad de California-Davis.

Las aves acuáticas como los patos y los gansos son las fuentes habituales de brotes en granjas avícolas, y los investigadores pueden detectar su proximidad mediante el uso de sensores remotos y otras tecnologías. Eso puede significar una vigilancia rutinaria para detectar signos tempranos de infecciones en aves de corral, usar cañones de agua para ahuyentar a las bandadas migratorias, reubicar animales de granja o llevarlos temporalmente a cobertizos. “Deberíamos estar invirtiendo en prevención”, dijo Pitesky.

Bien, no es una pandemia, pero ¿qué podría pasarle a las personas que contraigan la gripe aviar H5N1 de este año?

Realmente nadie lo sabe. Solo una persona en Texas fue diagnosticada con la enfermedad este año, en abril. Esta persona trabajaba con vacas lecheras, y tuvo un caso leve con una infección en el ojo. Los CDC se enteraron de esto debido a su proceso de vigilancia. Las clínicas deben alertar a los departamentos de salud estatales cuando diagnostican a trabajadores agrícolas con gripe, utilizando pruebas que detectan virus de la influenza en general.

Los departamentos de salud estatales luego confirman la prueba y, si es positiva, envían una muestra de la persona a un laboratorio de los CDC, donde se verifica específicamente la presencia del virus H5N1. “Hasta ahora hemos recibido 23”, dijo Shah. “Todos menos uno resultaron negativos”.

Agregó que funcionarios del departamento de salud estatal también están monitoreando a alrededor de 150 personas que han pasado tiempo alrededor de ganado. Están en contacto con estos trabajadores agrícolas con llamadas telefónicas, mensajes de texto o visitas en persona para ver si desarrollan síntomas. Y si eso sucede, les harán pruebas.

Otra forma de evaluar a los trabajadores agrícolas sería testear su sangre en busca de anticuerpos contra el virus de la gripe aviar H5N1; un resultado positivo indicaría que podrían haberse infectado sin saberlo. Pero Shah dijo que los funcionarios de salud aún no están haciendo este trabajo.

“El hecho de que hayan pasado cuatro meses y aún no hayamos hecho esto no es una buena señal”, dijo Worobey. “No estoy muy preocupado por una pandemia en este momento, pero deberíamos comenzar a actuar como si no quisiéramos que sucediera”.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 4 months ago

Health Industry, Noticias En Español, Public Health, Rural Health, Colorado, FDA, Food Safety, New Mexico, texas

Rural Americans Are Way More Likely To Die Young. Why?

Three words are commonly repeated to describe rural America and its residents: older, sicker and poorer.

Obviously, there’s a lot more going on in the nation’s towns than that tired stereotype suggests. But a new report from the Agriculture Department’s Economic Research Service gives credence to the “sicker” part of the trope.

Three words are commonly repeated to describe rural America and its residents: older, sicker and poorer.

Obviously, there’s a lot more going on in the nation’s towns than that tired stereotype suggests. But a new report from the Agriculture Department’s Economic Research Service gives credence to the “sicker” part of the trope.

Rural Americans ages 25 to 54 — considered the prime working-age population — are dying of natural causes such as chronic diseases and cancer at wildly higher rates than their age-group peers in urban areas, according to the report.

The USDA researchers analyzed mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from two three-year periods — 1999 through 2001, and 2017 through 2019. In 1999, the natural-cause mortality rate for rural working-age adults was only 6 percent higherthan that of their city-dwelling peers. By 2019, the gap had widened to 43 percent.

The disparity was significantly worse for women — and for Native American women, in particular. The gap highlights how persistent difficulties accessing health care, and a dispassionate response from national leaders, can eat away at the fabric of rural communities.

A possible Medicaid link

USDA researchers and other experts noted that states in the South that have declined to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act had some of the highest natural-cause mortality rates for rural areas. But the researchers didn’t pinpoint the causes of the overall disparity.

Seven of the 10 states that have not expanded Medicaid are in the South, though that could change soon because some lawmakers are rethinking their opposition, as KFF Health News previously reported.

The USDA’s findings were shocking but not surprising, said Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association. He and other health experts have maintained for years that rural America needs more attention and investment in its healthcare systems by national leaders and lawmakers.

Another recent report, from the health analytics and consulting firm Chartis, identified 418 rural hospitals that are “vulnerable to closure.” Congress, trying to slow the collapse of rural health infrastructure, enacted the Rural Emergency Hospital designation, which became available last year.

That new classification aimed to keep some facilities from shuttering in smaller towns by allowing hospitals to discontinue many inpatient services. But it has so far attracted only about 21of the hundreds of hospitals that qualify.

It’s unlikely that things have improved for rural Americans since 2019, the last year in the periods the USDA researchers examined. The coronavirus pandemic was particularly devastating in rural parts of the country.

Morgan wondered: How wide is the gap today? Congress, Morgan said, should direct the CDC to examine life expectancy in rural America before and after the pandemic: “Covid really changed the nature of public health in rural America.”

The National Rural Health Association’s current advocacy efforts include raising support on policies before Congress, including strengthening the rural health workforce and increasing funding for various initiatives focused on rural hospitals, sustaining obstetrics services, expanding physician training and addressing the opioid response, among others.

This article is not available for syndication due to republishing restrictions. If you have questions about the availability of this or other content for republication, please contact NewsWeb@kff.org.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 5 months ago

Rural Health, The Health 202

Swap Funds or Add Services? Use of Opioid Settlement Cash Sparks Strong Disagreements

State and local governments are receiving billions of dollars in opioid settlements to address the drug crisis that has ravaged America for decades.

State and local governments are receiving billions of dollars in opioid settlements to address the drug crisis that has ravaged America for decades. But instead of spending the money on new addiction treatment and prevention services they couldn’t afford before, some jurisdictions are using it to replace existing funding and stretch tight budgets.

Scott County, Indiana, for example, has spent more than $250,000 of opioid settlement dollars on salaries for its health director and emergency medical services staff. The money usually budgeted for those salaries was freed to buy an ambulance and create a financial cushion for the health department.

In Blair County, Pennsylvania, about $320,000 went to a drug court the county has been operating with other sources of money for more than two decades.

And in New York, some lawmakers and treatment advocates say the governor’s proposed budget substitutes millions of opioid settlement dollars for a portion of the state addiction agency’s normal funding.

The national opioid settlements don’t prohibit the use of money for initiatives already supported by other means. But families affected by addiction, recovery advocates, and legal and public health experts say doing so squanders a rare opportunity to direct additional resources toward saving lives.

“To think that replacing what you’re already spending with settlement funds is going to make things better — it’s not,” said Robert Kent, former general counsel for the Office of National Drug Control Policy. “Certainly, the spirit of the settlements wasn’t to keep doing what you’re doing. It was to do more.”

Settlement money is a new funding stream, separate from tax dollars. It comes from more than a dozen companies that were accused of aggressively marketing and distributing prescription painkillers. States are required to spend at least 85% of the funds on addressing the opioid crisis. Now, with illicit fentanyl flooding the drug market and killing tens of thousands of Americans annually, the need for treatment and social services is more urgent.

Thirteen states and Washington, D.C., have restricted the practice of substituting opioid settlement funds for existing dollars, according to state guides created by OpioidSettlementTracker.com and the public health organization Vital Strategies. A national set of principles created by Johns Hopkins University also advises against the practice, known as supplantation.

Paying Staff Salaries

Scott County, Indiana — a small, rural place known nationally as the site of an HIV outbreak in 2015 sparked by intravenous drug use — received more than $570,000 in opioid settlement funds in 2022.

From August 2022 to July 2023, the county reported using roughly $191,000 for the salaries of its EMS director, deputy director, and training officer/clinical coordinator, as well as about $60,000 for its health administrator. The county also awarded about $151,000 total to three community organizations that address addiction and related issues.

In a public meeting discussing the settlement dollars, county attorney Zachary Stewart voiced concerns. “I don’t know whether or not we’re supposed to be using that money to add, rather than supplement, already existing resources,” he said.

But a couple of months later, the county council approved the allocations.

Council President Lyndi Hughbanks did not respond to repeated requests to explain this decision. But council members and county commissioners said in public meetings that they hoped to compensate county departments for resources expended during the HIV outbreak.

Their conversations echoed the struggles of many rural counties nationwide, which have tight budgets, in part because they poured money into addressing the opioid crisis for years. Now as they receive settlement funds, they want to recoup some of those expenses.

The Scott County Health Department did not respond to questions about how the funds typically allocated for salary were used instead. But at the public meeting, it was suggested they could be used at the department’s discretion.

EMS Chief Nick Oleck told KFF Health News the money saved on salaries was put toward loan payments for a new ambulance, purchased in spring 2023.

Unlike other departments, which are funded from local tax dollars and start each year with a full budget, the county EMS is mostly funded through insurance reimbursements for transporting patients, Oleck said. The opioid settlement funds provided enough cash flow to make payments on the new ambulance while his department waited for reimbursements.

Oleck said this use of settlement dollars will save lives. His staff needs vehicles to respond to overdose calls, and his department regularly trains area emergency responders on overdose response.

“It can be played that it was just money used to buy an ambulance, but there’s a lot more behind the scenes,” Oleck said.

Still, Jonathan White — the only council member to vote against using settlement funds for EMS salaries — said he felt the expense did not fit the money’s intended purpose.

The settlement “was written to pay for certain things: helping people get off drugs,” White told KFF Health News. “We got drug rehab facilities and stuff like that that I believe could have used that money more.”

Phil Stucky, executive director of a local nonprofit called Thrive, said his organization could have used the money too. Founded in the wake of the HIV outbreak, Thrive employs people in recovery to provide support to peers with mental health and substance use disorders.

Stucky, who is in recovery himself, asked Scott County for $300,000 in opioid settlement funds to hire three peer specialists and purchase a vehicle to transport people to treatment. He ultimately received one-sixth of that amount — enough to hire one person.

In Blair County, Pennsylvania, Marianne Sinisi was frustrated to learn her county used about $322,000 of opioid settlement funds to pay for a drug court that has existed for decades.

“This is an opioid epidemic, which is not being treated enough as it is now,” said Sinisi, who lost her 26-year-old son to an overdose in 2018. The county received extra money to help people, but instead it pulled back its own money, she said. “How do you expect that to change? Isn’t that the definition of insanity?”

Blair County Commissioner Laura Burke told KFF Health News that salaries for drug court probation officers and aides were previously covered by a state grant and parole fees. But in recent years that funding has been inadequate, and the county general fund has picked up the slack. Using opioid settlement funds provides a small reprieve since the general fund is overburdened, she said. The county’s most recent budget faces a $2 million deficit.

Forfeited Federal Dollars

Supplantation can take many forms, said Shelly Weizman, project director of the addiction and public policy initiative at Georgetown University’s O’Neill Institute. Replacing general funds with opioid settlement dollars is an obvious one, but there are subtler approaches.

The federal government pours billions of dollars into addiction-related initiatives annually. But some states forfeit federal grants or decline to expand Medicaid, which is the largest payer of mental health and addiction treatment.

If those jurisdictions then use opioid settlement funds for activities that could have been covered with federal money, Weizman considers it supplantation.

“It’s really letting down the citizens of their state,” she said.

Officials in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, forfeited more than $1 million in federal funds from September 2022 to September 2023, the bulk of which was meant to support the construction of a behavioral health crisis stabilization center.

“We were probably overly optimistic” about spending the money by the grant deadline, said Diane Rosati, executive director of the Bucks County Drug and Alcohol Commission.

Now the county plans to use $3.9 million in local and state opioid settlement funds to support the center.

Susan Ousterman finds these developments difficult to stomach. Her 24-year-old son died of an overdose in 2020, and she later joined the Bucks County Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee, which developed a plan to spend the funds.

In a September 2022 email to other committee members, she expressed disappointment in the suggested uses: “Please keep in mind, the settlement funds are not meant to fund existing programs or programs that can be funded by other sources, such as federal grants.”

But Rosati said the county is maximizing its resources. Settlement funds will create a host of services, including grief groups for families and transportation to treatment facilities.

“We’re determined to utilize every bit of funding that’s available to Bucks County, using every funding source, every stream, and frankly every grant opportunity that comes our way,” Rosati said.

The county’s guiding principles for settlement funds demand as much. They say, “Whenever possible, use existing resources in order that Opioid Settlement funds can be directed to addressing gaps in services.”

Ed Mahon of Spotlight PA contributed to this report.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 5 months ago

Courts, Rural Health, States, Indiana, Investigation, New York, Opioid Settlements, Opioids, Pennsylvania

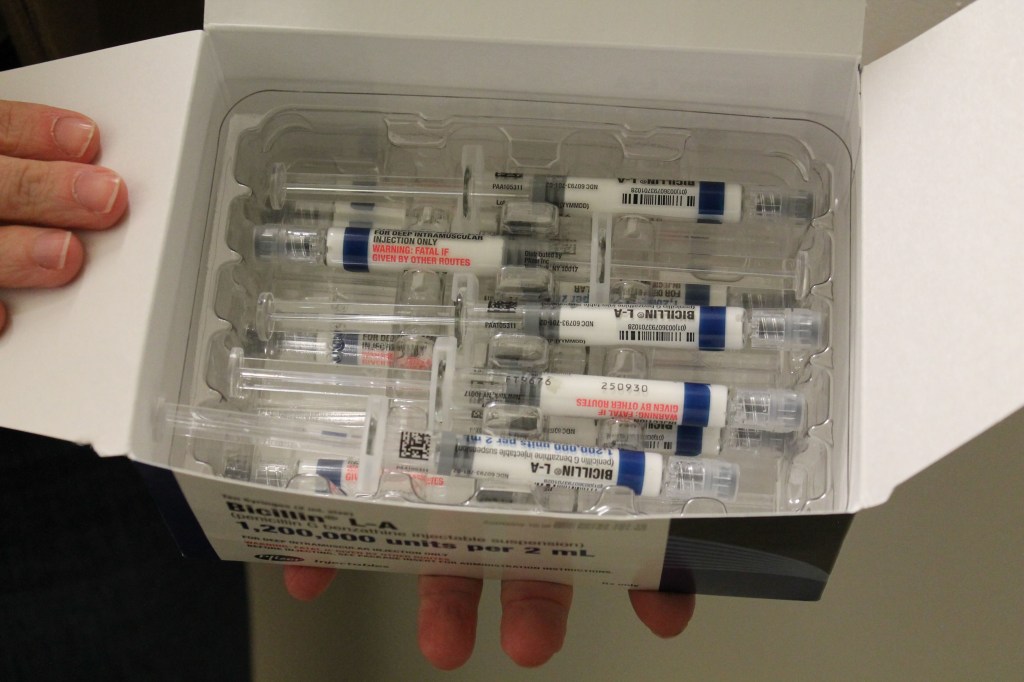

Surge in Syphilis Cases Leads Some Providers to Ration Penicillin

When Stephen Miller left his primary care practice to work in public health a little under two years ago, he said, he was shocked by how many cases of syphilis the clinic was treating.

For decades, rates of the sexually transmitted infection were low. But the Hamilton County Health Department in Chattanooga — a midsize city surrounded by national forests and nestled into the Appalachian foothills of Tennessee — was seeing several syphilis patients a day, Miller said. A nurse who had worked at the clinic for decades told Miller the wave of patients was a radical change from the norm.

What Miller observed in Chattanooga is reflective of a trend that is raising alarm bells for health departments across the country.

Nationwide, syphilis rates are at a 70-year high. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Jan. 30 that 207,255 cases were reported in 2022, continuing a steep increase over five years. Between 2018 and 2022, syphilis rates rose about 80%. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections — especially syphilis — is “out of control,” said the National Coalition of STD Directors.

The surge has been even more pronounced in Tennessee, where infection rates for the first two stages of syphilis grew 86% between 2017 and 2021.

But this already difficult situation was complicated last spring by a shortage of a specific penicillin injection that is the go-to treatment for syphilis. The ongoing shortage is so severe that public health agencies have recommended that providers ration the drug — prioritizing pregnant patients, since it is the only syphilis treatment considered safe for them. Congenital syphilis, which happens when the mom spreads the disease to the fetus, can cause birth defects, miscarriages, and stillbirths.

Across the country, 3,755 cases of congenital syphilis were reported to the CDC in 2022 — that’s 10 times as high as the number a decade before, the recent data shows. Of those cases, 231 resulted in stillbirth and 51 led to infant death. The number of cases in babies swelled by 183% between 2018 and 2022.

“Lack of timely testing and adequate treatment during pregnancy contributed to 88% of cases of congenital syphilis,” said a report from the CDC released in November. “Testing and treatment gaps were present in the majority of cases across all races, ethnicities, and U.S. Census Bureau regions.”

Hamilton County’s syphilis rates have mirrored the national trend, with an increase in cases for all groups, including infants.

In November, the maternal and infant health advocacy organization March of Dimes released its annual report on states’ health outcomes. It found that, nationwide, about 15.5% of pregnant people received care beginning in the fifth month of pregnancy or later — or attended fewer than half the recommended prenatal visits. In Tennessee, the rate was even worse, 17.4%.

But Miller said even those who attend every recommended appointment can run into problems because providers are required to test for syphilis only at the beginning of a pregnancy. The idea is that if you test a few weeks before birth, there is time to treat the infection.

However, that recommendation hinges on whether the provider suspects the patient was exposed to the bacterium that causes syphilis, which may not be obvious for people who say their relationships are monogamous.

“What we found is, a lot of times their partner was not as monogamous, and they were bringing it into the relationship,” Miller said.

Even if the patient tested negative initially, they may have contracted syphilis later in pregnancy, when testing for the disease is not routine, he said.

Two antibiotics are used to treat syphilis, the injectable penicillin and an oral drug called doxycycline.

Patients allergic to penicillin are often prescribed the oral antibiotic. But the World Health Organization strongly advises pregnant patients to avoid doxycycline because it can cause severe bone and teeth deformities in the infant.

As a result, pregnant syphilis patients are often given penicillin, even when they’re allergic, using a technique called desensitization, said Mark Turrentine, a Houston OB-GYN. Patients are given low doses in a hospital setting to help their bodies get used to the drug and to check for a severe reaction. The penicillin shot is a one-and-done technique, unlike an antibiotic, which requires sticking to a two-week regimen.

“It’s tough to take a medication for a long period of time,” Turrentine said. The single injection can provide patients and their clinicians peace of mind. “If they don’t come back for whatever reason, you’re not worried about it,” he said.

The Metro Public Health Department in Nashville, Tennessee, began giving all nonpregnant adults with syphilis the oral antibiotic in July, said Laura Varnier, nursing and clinical director.

Turrentine said he started seeing advisories about the injectable penicillin shortage in April, around the time the antibiotic amoxicillin became difficult to find and physicians were using penicillin as a substitute, potentially precipitating the shortage, he said.

The rise in syphilis has created demand for the injection that manufacturer Pfizer can’t keep up with, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. “There is insufficient supply for usual ordering,” the ASHP said in a memo.

Even though penicillin has been around a long time, manufacturing it is difficult, largely because so many people are allergic, said Erin Fox, associate chief pharmacy officer for the University of Utah health system and an adjunct professor at the university, who studies drug shortages.

“That means you can’t make other drugs on that manufacturing line,” she said. Only major manufacturers like Pfizer have the resources to build and operate such a specialized, cordoned-off facility. “It’s not necessarily efficient — or necessarily profitable,” Fox said.

In a statement, Pfizer confirmed the amoxicillin shortage and surge in syphilis increased demand for injectable penicillin by about 70%. Representatives said the company invested $38 million in the facility that produces this form of penicillin, hiring more staff and expanding the production line.

“This ramp up will take some time to be felt in the market, as product cycle time is 3-6 months from when product is manufactured to when it is available to be released to customers,” the statement reads. The company estimated the shortage would be significantly alleviated by spring.

In the meantime, Miller said, his clinic in Chattanooga is continuing to strategize. Each dose of injectable penicillin can cost hundreds of dollars. Plus, it has to be placed in cold storage, and it expires after 48 months.

Even with the dramatic increase in cases, syphilis is still relatively rare. More than 7 million people live in Tennessee, and in 2019, providers statewide reported 683 cases of syphilis.

Health departments like Miller’s treat the bulk of syphilis patients. Many patients are sent by their provider to the health department, which works with contact tracers to identify and notify sexual partners who might be affected and tests patients for other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

“When you diagnose in the office, think of it as just seeing the tip of the iceberg,” Miller said. “You need a team of individuals to be able to explore and look at the rest of the iceberg.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes WPLN, NPR, and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 7 months ago

Pharmaceuticals, Public Health, Rural Health, States, CDC, Sexual Health, Tennessee

Hospitales rurales, atrapados en el dilema de sus viejas infraestructuras

Kevin Stansbury, CEO del Lincoln Community Hospital de Hugo, un pueblo de 800 habitantes en Colorado, se enfrenta a un clásico dilema: podría aumentar los ingresos de su hospital rural ofreciendo prótesis de cadera y operaciones de hombro, pero el centro de salud, con 64 años de antigüedad, necesita más dinero para poder ampliar su quirófano y realizar es

Kevin Stansbury, CEO del Lincoln Community Hospital de Hugo, un pueblo de 800 habitantes en Colorado, se enfrenta a un clásico dilema: podría aumentar los ingresos de su hospital rural ofreciendo prótesis de cadera y operaciones de hombro, pero el centro de salud, con 64 años de antigüedad, necesita más dinero para poder ampliar su quirófano y realizar esas intervenciones.

“Tengo un cirujano dispuesto a hacerlo; pero mis instalaciones no son lo bastante grandes”, dijo Stansbury. “Y en mi hospital no puedo hacer servicios urgentes como obstetricia porque mi instalación no cumple con el código”.

Además de asegurar ingresos adicionales para el hospital, una ampliación de este tipo podría evitar que los habitantes de la zona tengan que conducir 100 millas hasta Denver para someterse a operaciones ortopédicas o dar a luz.

Los hospitales rurales a lo largo del país se enfrentan a un dilema similar.

El aumento de los costos, en medio de reducciones de los pagos de las aseguradoras, dificulta que los pequeños hospitales obtengan financiación para grandes renovaciones. Además, la elevada inflación y el aumento de las tasas de interés, como consecuencia de la pandemia, complica la obtención de préstamos u otros tipos de financiación para modernizar las instalaciones y adaptarlas a los estándares de la atención médica en constante cambio.

“La mayoría trabajamos con márgenes muy bajos, si es que tenemos alguno”, afirmó Stansbury. “Así que nos cuesta encontrar el dinero”.

El envejecimiento de las infraestructuras hospitalarias, sobre todo en las zonas rurales, es un problema que va en aumento. Los datos sobre la edad de los hospitales son difíciles de conseguir, porque se amplían, modernizan y remodelan diferentes partes de sus instalaciones a lo largo del tiempo.

Un análisis de 2017 de la American Society for Health Care Engineering, que forma parte de la American Hospital Association, descubrió que la edad media de los hospitales en Estados Unidos aumentó de 8,6 años en 1994 a 11,5 años en 2015. Ese número probablemente ha crecido, según conocedores de la industria, ya que muchos hospitales retrasaron los proyectos de mejora, particularmente durante la pandemia.

Una investigación publicada en 2021 por la empresa de planificación de capital Facility Health Inc, ahora llamada Brightly, reportó que los centros de salud estadounidenses habían aplazado un 41% de su mantenimiento y necesitarían $243,000 millones para ponerse al día.

Los hospitales rurales no disponen de los recursos de los grandes hospitales, sobre todo los que forman parte de cadenas hospitalarias, para financiar ampliaciones multimillonarias.

La mayoría de los hospitales rurales en funciones hoy se abrieron con fondos del Hill-Burton Act, una ley aprobada por el Congreso en 1946. Este programa se integró en la Ley de Servicios de Salud Pública en la década de 1970 y, en 1997, había financiado la construcción de casi 7,000 hospitales y clínicas. Ahora, muchos de esos edificios, sobre todo los rurales, necesitan mejoras urgentes.

Stansbury, que también preside el consejo de administración de la Colorado Hospital Association, señaló que al menos media docena de hospitales rurales del estado necesitan importantes inversiones de capital.

Harold Miller, presidente y CEO del Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, un think tank de Pittsburgh, afirmó que el principal problema de los pequeños hospitales rurales es que los seguros privados ya no cubren el costo total de la asistencia. Según Miller, Medicare Advantage, un programa por el que Medicare paga a planes privados para dar cobertura a personas mayores y discapacitadas, es uno de los principales responsables del problema.

“Básicamente, apartan a los pacientes de lo que puede ser el mejor pagador que tiene un pequeño hospital, y se los llevan a un plan privado, que no paga de la misma manera que Medicare tradicional y termina utilizando una variedad de técnicas para rechazar los reclamos”, explicó Miller.

Además, los hospitales rurales deben dotar sus servicios de urgencias de médicos las 24 horas del día, pero sólo cobran si hay pacientes.

Mientras tanto, los costos laborales desde el fin de la pandemia han aumentado, y la inflación ha disparado el precio de los suministros. Es probable que estas dificultades financieras obliguen a cerrar más hospitales rurales.

Los cierres de hospitales se redujeron durante la pandemia, de un récord de 18 cierres en 2020 a un total de ocho cierres en 2021 y 2022, según el Centro Cecil G. Sheps para la Investigación de Servicios de Salud de la Universidad de Carolina del Norte-Chapel Hill, porque los fondos de ayuda de emergencia los mantuvieron abiertos. Pero ese soporte vital ha terminado, y al menos nueve más cerraron en 2023. Según Miller, los cierres han vuelto a los niveles anteriores a la pandemia.

Esto hace temer que algunos hospitales inviertan en nuevas instalaciones y acaben cerrando de todos modos. Miller aseguró que sólo una pequeña parte de los hospitales rurales conseguiría una mejora significativa en sus finanzas agregando nuevos servicios.

Legisladores han intentado ayudar. California, por ejemplo, cuenta con programas de préstamos a bajo o ningún interés en los que pueden participar los hospitales rurales, y representantes de los hospitales le han pedido a los legisladores de Colorado que aprueben ayudas similares.

A nivel federal, la legisladora Yadira Caraveo, demócrata de Colorado, ha presentado el proyecto de ley bipartidista Rural Health Care Facilities Revitalization Act, que ayudaría a los hospitales rurales a obtener más fondos a través del Departamento de Agricultura de Estados Unidos (USDA).

El USDA ha sido uno de los mayores financiadores del desarrollo rural a través de los Community Facilities Programs, proporcionando más de $3 mil millones en préstamos al año. En 2019, la mitad de los más de $10 mil millones en préstamos pendientes a través del programa ayudaron a instalaciones de salud.

“De lo contrario, los centros tendrían que recurrir a prestamistas privados”, dijo Carrie Cochran-McClain, directora de la National Rural Health Association.

Los hospitales rurales pueden no resultar muy atractivos para los prestamistas privados debido a sus limitaciones financieras, y por lo tanto tendrían que pagar tasas de interés más altas o cumplir requisitos adicionales para obtener esos préstamos, agregó.

El proyecto de ley de Caraveo también permitiría a los hospitales, que ya tienen préstamos, refinanciarlos a tipos de interés más bajos, y cubriría más categorías de equipos médicos, como los dispositivos y la tecnología utilizados para la telesalud.

“Tenemos que mantener estos centros abiertos, no sólo para urgencias, sino también para dar a luz o para una consulta de cardiología”, explicó Caraveo, que también es pediatra. “No deberías tener que conducir dos o tres horas para tener esos servicios”.

Kristin Juliar, consultora de recursos de capital de la National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health, ha estudiado los retos a los que se enfrentan los hospitales rurales a la hora de pedir dinero prestado y planificar grandes proyectos.

“Intentan hacer esto mientras realizan su trabajo habitual dirigiendo un hospital”, dijo Juliar. “Por ejemplo, muchas veces, cuando surgen oportunidades de financiación, la agenda puede ser demasiado ajustada para que puedan desarrollar un proyecto”.

Parte de la financiación depende de que el hospital consiga fondos de contrapartida, lo que puede resultar difícil en comunidades rurales de bajos recursos. Y la mayoría de los proyectos exigen que los hospitales reúnan fondos de varias fuentes, lo que suma complejidad.

Y como la elaboración de estos proyectos suele llevar mucho tiempo, los CEO o los miembros del consejo de administración de los hospitales rurales a veces dejan el cargo antes de que se finalicen.

“Te pones manos a la obra y luego desaparecen personas clave, y entonces te sientes como si empezaras de nuevo”, explicó Juliar.

El hospital de Hugo abrió sus puertas en 1959, por iniciativa de los soldados que regresaban de la Segunda Guerra Mundial al condado de Lincoln, en las llanuras del este de Colorado. Donaron dinero, materiales, terrenos y mano de obra para construirlo. El hospital ha agregado cuatro clínicas de medicina familiar, un centro de enfermería especializada y un centro de vida asistida fuera de las instalaciones. Y atrae a especialistas de Denver y Colorado Springs.

A Stansbury le gustaría construir un nuevo hospital de aproximadamente el doble de tamaño que el actual, de 45,000 pies cuadrados. Dado que la inflación está bajando y es probable que las tasas de interés bajen este año, Stansbury espera conseguir financiación en 2024 y empezar a construir en 2025.

“El problema es que cada día que me despierto es más caro”, afirmó Stansbury.

Cuando autoridades del hospital se plantearon por primera vez la construcción de un nuevo hospital hace tres años, calcularon que el costo total del proyecto rondaría los $65 millones. Pero la inflación se disparó y ahora han subido las tasas de interés, lo que ha elevado el costo total a $75 millones.

“Si tenemos que esperar un par de años más, puede que nos acerquemos a los $80 millones”, señaló Stansbury. “Pero tenemos que hacerlo. No puedo esperar cinco años y pensar que los costos de construcción van a bajar”.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 8 months ago

Health Industry, Noticias En Español, Rural Health, States, Colorado

Can Family Doctors Deliver Rural America From Its Maternal Health Crisis?

CAIRO, Ga. — Zita Magloire carefully adjusted a soft measuring tape across Kenadie Evans’ pregnant belly.

Determining a baby’s size during a 28-week obstetrical visit is routine. But Magloire, a family physician trained in obstetrics, knows that finding the mother’s uterus and, thus, checking the baby, can be tricky for inexperienced doctors.

CAIRO, Ga. — Zita Magloire carefully adjusted a soft measuring tape across Kenadie Evans’ pregnant belly.

Determining a baby’s size during a 28-week obstetrical visit is routine. But Magloire, a family physician trained in obstetrics, knows that finding the mother’s uterus and, thus, checking the baby, can be tricky for inexperienced doctors.

“Sometimes it’s, like, off to the side,” Magloire said, showing a visiting medical student how to press down firmly and complete the hands-on exam. She moved her finger slightly to calculate the fetus’s height: “There she is, right here.”

Evans smiled and later said Magloire made her “comfortable.”

The 21-year-old had recently relocated from Louisiana to southeastern Georgia, two states where both maternal and infant mortality are persistently high. She moved in with her mother and grandfather near Cairo, an agricultural community where the hospital has a busy labor and delivery unit. Magloire and other doctors at the local clinic where she works deliver hundreds of babies there each year.

Scenes like the one between Evans and Magloire regularly play out in this rural corner of Georgia despite grim realities mothers and babies face nationwide. Maternal deaths keep rising, with Black and Indigenous mothers most at risk; the number of babies who died before their 1st birthday climbed last year; and more than half of all rural counties in the United States have no hospital services for delivering babies, increasing travel time for parents-to-be and causing declines in prenatal care.

There are many reasons labor and delivery units close, including high operating costs, declining populations, low Medicaid reimbursement rates, and staffing shortages. Family medicine physicians still provide the majority of labor and delivery care in rural America, but few new doctors recruited to less populated areas offer obstetrics care, partly because they don’t want to be on call 24/7. Now, with rural America hemorrhaging health care providers, the federal government is investing dollars and attention to increase the ranks.

“Obviously the crisis is here,” said Hana Hinkle, executive director of the Rural Training Track Collaborative, which works with more than 70 rural residency training programs. Federal grants have boosted training programs in recent years, Hinkle said.

In July, the Department of Health and Human Services announced a nearly $11 million investment in new rural programs, including family medicine residencies that focus on obstetrical training.

Nationwide, a declining number of primary care doctors — internal and family medicine — has made it difficult for patients to book appointments and, in some cases, find a doctor at all. In rural America, training family medicine doctors in obstetrics can be more daunting because of low government reimbursement and increasing medical liability costs, said Hinkle, who is also assistant dean of Rural Health Professions at the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Rockford.

In the 1980s, about 43% of general family physicians who completed their residencies were trained in obstetrics. In 2021, the American Academy of Family Physicians’ annual practice profile survey found that 15% of respondents had practiced obstetrics.

Yet family doctors, who also provide the full spectrum of primary care services, are “the backbone of rural deliveries,” said Julie Wood, a doctor and senior vice president of research, science, and health of the public at the AAFP.

In a survey of 216 rural hospitals in 10 states, family practice doctors delivered babies in 67% of the hospitals, and at 27% of the hospitals they were the only ones who delivered babies. The data counted babies delivered from 2013 to 2017. And, the authors found, if those family physicians hadn’t been there, many patients would have driven an average of 86 miles round-trip for care.

Mark Deutchman, the report’s lead author, said he was “on call for 12 years” when he worked in a town of 2,000 residents in rural Washington. Clarifying that he was exaggerating, Deutchman explained that he was one of just two local doctors who performed cesarean sections. He said the best way to ensure family physicians can bolster obstetric units is to make sure they work as part of a team to prevent burnout, rather than as solo do-it-all doctors of old.

There needs to be a core group of physicians, nurses, and a supportive hospital administration to share the workload “so that somebody isn’t on call 365 days a year,” said Deutchman, who is also associate dean for rural health at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine. The school’s College of Nursing received a $2 million federal grant this fall to train midwives to work in rural areas of Colorado.

Nationwide, teams of providers are ensuring rural obstetric units stay busy. In Lakin, Kansas, Drew Miller works with five other family physicians and a physician assistant who has done an obstetrical fellowship. Together, they deliver about 340 babies a year, up from just over 100 annually when Miller first moved there in 2010. Word-of-mouth and two nearby obstetric unit closures have increased their deliveries. Miller said he has seen friends and partners “from surrounding communities stop delivering just from sheer burnout.”

In Galesburg, Illinois, Annevay Conlee has watched four nearby obstetric units close since 2012, forcing some pregnant people to drive up to an hour and a half for care. Conlee is a practicing family medicine doctor and medical director overseeing four rural areas with a team of OB-GYNs, family physicians, and a nurse-midwife. “There’s no longer the ability to be on 24/7 call for your women to deliver,” Conlee said. “There needs to be a little more harmony when recruiting in to really support a team of physicians and midwives.”

In Cairo, Magloire said practicing obstetrics is “just essential care.” In fact, pregnancy care represents just a slice of her patient visits in this Georgia town of about 10,000 people. On a recent morning, Magloire’s patients included two pregnant people as well as a teen concerned about hip pain and an ecstatic 47-year-old who celebrated losing weight.

Cairo Medical Care, an independent clinic situated across the street from the 60-bed Archbold Grady hospital, is in a community best known for its peanut crops and as the birthplace of baseball legend Jackie Robinson. The historical downtown has brick-accented streets and the oldest movie theater in Georgia, and a corner of the library is dedicated to local history.

The clinic’s six doctors, who are a mix of family medicine practitioners, like Magloire, and obstetrician-gynecologists, pull in patients from the surrounding counties and together deliver nearly 300 babies at the hospital each year.

Deanna Buckins, a 36-year-old mother of four boys, said she was relieved when she found “Dr. Z” because she “completely changed our lives.”

“She actually listens to me and accepts my decisions instead of pushing things upon me,” said Buckins, as she held her 3-week-old son, whom Magloire had delivered. Years earlier, Magloire helped diagnose one of Buckins’ older children with autism and built trust with the family.

“Say I go in with one kid; before we leave, we’ve talked about every single kid on how they’re doing and, you know, getting caught up with life,” Buckins said.

Magloire grew up in Tallahassee, Florida, and did her residency in rural Kansas. The smallness of Cairo, she said, allows her to see patients as they grow — chatting up the kids when the mothers or siblings come for appointments.

“She’s very friendly,” Evans said of Magloire. Evans, whose first child was delivered by an OB-GYN, said she was nervous about finding the right doctor. The kind of specialist her doctor was didn’t matter as much as being with “someone who cares,” she said.

As a primary care doctor, Magloire can care for Evans and her children for years to come.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 8 months ago

Health Industry, Rural Health, Children's Health, Colorado, Doctors, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Pregnancy, Women's Health

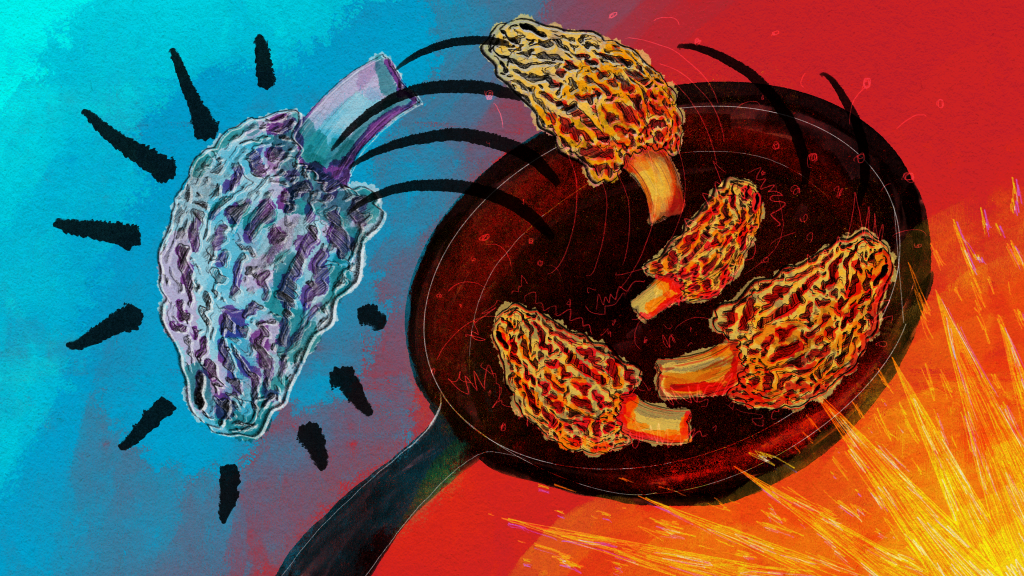

Mysterious Morel Mushrooms at Center of Food Poisoning Outbreak

A food poisoning outbreak that killed two people and sickened 51, stemming from a Montana restaurant, has highlighted just how little is known about morel mushrooms and the risks in preparing the popular and expensive delicacy.

The FDA conducted an investigation into morel mushrooms after the severe illness outbreak linked to Dave’s Sushi in Bozeman in late March and April. The investigation found that undercooked or raw morels were the likely culprit, and it led the agency to issue its first guidelines on preparing morels.

“The toxins in morel mushrooms that may cause illness are not fully understood; however, using proper preparation procedures, such as cooking, can help to reduce toxin levels,” according to the FDA guidance.

Even then, a risk remains, according to the FDA: “Properly preparing and cooking morel mushrooms can reduce risk of illness, however there is no guarantee of safety even if cooking steps are taken prior to consumption.”

Jon Ebelt, spokesperson for Montana’s health department, said there is limited public health information or medical literature on morels. And samples of the morels taken from Dave’s Sushi detected no specific toxin, pathogen, pesticide, or volatile or nonvolatile organic compound in the mushrooms.

Aaron Parker, the owner of Dave’s Sushi, said morels are a “boutique item.” In season, generally during the spring and fall, morels can cost him $40 per pound, while morels purchased out of season are close to $80 per pound, he said.

Many highly regarded recipe books describe sauteing morels to preserve the sought-after, earthy flavor. At Dave’s, a marinade, sometimes boiling, was poured over the raw mushrooms before they were served, Parker said. After his own investigation, Parker said he found boiling them between 10 and 30 minutes is the safest way to prepare morel mushrooms.

Parker said he reached out to chefs across the country and found that many, like him, were surprised to learn about the toxicity of morels.

“They had no idea that morel mushrooms had this sort of inherent risk factor regardless of preparation,” Parker said.

According to the FDA’s Food Code, the vast majority of the more than 5,000 fleshy mushroom species that grow naturally in North America have not been tested for toxicity. Of those that have, 15 species are deadly, 60 are toxic whether raw or cooked — including “false” morels, which look like spongy edible morels — and at least 40 are poisonous if eaten raw, but safer when cooked.

The North American Mycological Association, a national nonprofit whose members are mushroom experts, recorded 1,641 cases of mushroom poisonings and 17 deaths from 1985 to 2006. One hundred and twenty-nine of those poisonings were attributed to morels, but no deaths were reported.

Marian Maxwell, the outreach chairperson for the Puget Sound Mycological Society, based in Seattle, said cooking breaks down the chitin in mushrooms, the same compound found in the exoskeletons of shellfish, and helps destroy toxins. Maxwell said morels may naturally contain a type of hydrazine — a chemical often used in pesticides or rocket fuel that can cause cancer — which can affect people differently. Cooking does boil off the hydrazine, she said, “but some people still have reactions even though it’s cooked and most of that hydrazine is gone.”

Heather Hallen-Adams, chair of the toxicology committee of the North American Mycological Association, said hydrazine has been shown to exist in false morels, but it’s not as “clear-cut” in true morels, which were the mushrooms used at Dave’s Sushi.

Mushroom-caused food poisonings in restaurant settings are rare — the Montana outbreak is believed to be one of the first in the U.S. related to morels — but they have happened infrequently abroad. In 2019, a morel food poisoning outbreak at a Michelin-star-rated restaurant in Spain sickened about 30 customers. One woman who ate the morels died, but her death was determined to be from natural causes. Raw morels were served on a pasta salad in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 2019 and poisoned 77 consumers, though none died.

Before the new guidelines were issued, the FDA’s Food Code guidance to states was only that serving wild mushrooms must be approved by a “regulatory authority.”

The FDA’s Food Code bans the sale of wild-picked mushrooms in a restaurant or other food establishment unless it’s been approved to do so, though cultivated wild mushrooms can be sold if the cultivation operations are overseen by a regulatory agency, as was the case with the morels at Dave’s Sushi. States’ regulations vary, according to a 2021 study by the Georgia Department of Public Health and included in the Association of Food and Drug Officials’ regulatory guidelines. For example, Montana and a half-dozen other states allow restaurants to sell wild mushrooms if they come from a licensed seller, according to the study. Seventeen other states allow the sale of wild mushrooms that have been identified by a state-credentialed expert.

The study found that the varied resources states use to identify safe wild mushrooms — including mycological associations, academics, and the food service industry — may suggest a need for better communication.

The study recognized a “guidance document” as the “single most important step forward” given the variety in regulations and the demand for wild mushrooms.

Hallen-Adams said raw morels are known to be poisonous by “mushroom people,” but that’s not common knowledge among chefs.

In the Dave’s Sushi case, Hallen-Adams said, it was obvious that safety information didn’t get to the people who needed it. “And this could be something that could be addressed by labeling,” she said.

There hasn’t been much emphasis placed on making sure consumers know how to properly prepare the mushrooms, Hallen-Adams said, “and that’s something we need to start doing.”

Hallen-Adams, who trains people in Nebraska on mushroom identification, said the North American Mycological Association planned to update its website and include more prominent information about the need to cook mushrooms, with a specific mention of morels.

Montana’s health department intends to publish guidelines on morel safety in the spring, when morel season is approaching.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 9 months ago

Public Health, Rural Health, States, FDA, Food Safety, Montana

Extra Fees Drive Assisted Living Profits

Assisted living centers have become an appealing retirement option for hundreds of thousands of boomers who can no longer live independently, promising a cheerful alternative to the institutional feel of a nursing home.

But their cost is so crushingly high that most Americans can’t afford them.

Assisted living centers have become an appealing retirement option for hundreds of thousands of boomers who can no longer live independently, promising a cheerful alternative to the institutional feel of a nursing home.

But their cost is so crushingly high that most Americans can’t afford them.

What to Know About Assisted Living

The facilities can look like luxury apartments or modest group homes and can vary in pricing structures. Here’s a guide.

These highly profitable facilities often charge $5,000 a month or more and then layer on fees at every step. Residents’ bills and price lists from a dozen facilities offer a glimpse of the charges: $12 for a blood pressure check; $50 per injection (more for insulin); $93 a month to order medications from a pharmacy not used by the facility; $315 a month for daily help with an inhaler.

The facilities charge extra to help residents get to the shower, bathroom, or dining room; to deliver meals to their rooms; to have staff check-ins for daily “reassurance” or simply to remind residents when it’s time to eat or take their medication. Some even charge for routine billing of a resident’s insurance for care.

“They say, ‘Your mother forgot one time to take her medications, and so now you’ve got to add this on, and we’re billing you for it,’” said Lori Smetanka, executive director of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, a nonprofit.