KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Trump’s Bill Reaches the Finish Line

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

Early Thursday afternoon, the House approved a budget reconciliation bill that not only would make permanent many of President Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cuts, but also impose deep cuts to Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, and, indirectly, Medicare.

Meanwhile, those appointed by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to a key vaccine advisory panel used their first official meeting to cast doubt on a preservative that has been used in flu vaccines for decades — with studies showing no evidence of its harm in low doses.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico, Maya Goldman of Axios, and Sarah Karlin-Smith of the Pink Sheet.

Panelists

Maya Goldman

Axios

Sarah Karlin-Smith

Pink Sheet

@sarahkarlin-smith.bsky.social

Alice Miranda Ollstein

Politico

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- This week the GOP steamrolled toward a major constriction of the nation’s social safety net, pushing through Trump’s tax and spending bill. The legislation contains significant changes to the way Medicaid is funded and delivered — in particular, through imposing the program’s first federal work requirement on many enrollees. Hospitals say the changes would be devastating, potentially resulting in the loss of services and facilities that could touch all patients, not only those on Medicaid.

- Some proposals in Trump’s bill were dropped during the Senate’s consideration, including a ban on Medicaid coverage for gender-affirming care and federal funding cuts for states that use their own Medicaid funds to cover immigrants without legal status. And for all the talk of not touching Medicare, the legislation’s repercussions for the deficit are expected to trigger spending cuts to the program that covers those over 65 and some with disabilities — potentially as soon as the next fiscal year.

- The newly reconstituted Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices met last week, and it looked pretty different from previous meetings: In addition to new members, there were fewer staffers on hand from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — and the notable presence of vaccine critics. The panel’s vote to reverse the recommendation of flu shots containing a mercury-based preservative — plus its plans to review the childhood vaccine schedule — hint at what’s to come.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: The Lancet’s “Evaluating the Impact of Two Decades of USAID Interventions and Projecting the Effects of Defunding on Mortality up to 2030: A Retrospective Impact Evaluation and Forecasting Analysis,” by Daniella Medeiros Cavalcanti, et al.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: The New York Times’ “‘I Feel Like I’ve Been Lied To’: When a Measles Outbreak Hits Home,” by Eli Saslow.

Maya Goldman: Axios’ “New Docs Get Schooled in Old Diseases as Vax Rates Fall,” by Tina Reed.

Sarah Karlin-Smith: Wired’s “Snake Venom, Urine, and a Quest to Live Forever: Inside a Biohacking Conference Emboldened by MAHA,” by Will Bahr.

Also mentioned in this week’s episode:

- NBC News’ “Crisis Pregnancy Centers Told To Avoid Ultrasounds for Suspected Ectopic Pregnancies,” by Abigail Brooks.

- ProPublica’s “A ‘Striking’ Trend: After Texas Banned Abortion, More Women Nearly Bled to Death During Miscarriage,” by Kavitha Surana, Lizzie Presser, and Andrea Suozzo.

- The Washington Post’s “DOGE Loses Control Over Government Grants Website, Freeing Up Billions,” by Dan Diamond and Hannah Natanson.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Trump’s Bill Reaches the Finish Line

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, July 3, at 10 a.m. As always, and particularly this week, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via videoconference by Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Hello.

Rovner: Sarah Karlin-Smith at the Pink Sheet.

Sarah Karlin-Smith: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: And Maya Goldman of Axios News.

Maya Goldman: Good to be here.

Rovner: No interview this week, but more than enough news, so we will get right to it. So as we sit down to tape, the House is on the cusp of passing the biggest constriction of the federal social safety net ever, part of President [Donald] Trump’s, quote, “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which is technically no longer called that, because the name was ruled out of order when it went through the Senate. In an effort to get the bill to the president’s desk by the July Fourth holiday, aka tomorrow, the House had to swallow without changes the bill that passed the Senate on Tuesday morning after Vice President JD Vance broke a 50-50 tie. And the House has been in session continuously since Wednesday morning working to do just that, with lots of arm-twisting and threatening and cajoling to walk back the complaints from both conservative Republicans, who are objecting to the trillions of dollars the bill would add to the national debt, as well as moderates objecting to the Medicaid and food stamp cuts.

There is a whole lot to unpack here, but let’s start with Medicaid, which would take the biggest hit of the health programs in this bill — ironically, just weeks before the program’s 60th anniversary. What does this bill do to Medicaid?

Goldman: This bill makes some huge changes to the way that Medicaid is funded and delivered in the United States. One of the biggest changes is the first federal work requirement for Medicaid, which we’ve talked about at length.

Rovner: Pretty much every week.

Goldman: Pretty much every week. It’s going to be — it’s sort of death by paperwork for many people. They’re not necessarily forced to lose their coverage, but there are so many paperwork hurdles and barriers to making sure that you are reporting things correctly, that CBO [the Congressional Budget Office] expects millions of people are going to lose coverage. And we know from limited experiments with work requirements in Arkansas that it does not increase employment. So, that’s the biggie.

Rovner: The House froze provider taxes, which is what most — all states but Alaska? — use to help pay their share of Medicaid. The Senate went even further, didn’t they?

Goldman: Yeah. Hospitals are saying that it’s going to be absolutely devastating to them. When you cut funding, cut reimbursement in that way, cut the amount of money that’s available in that way, it trickles down to the patient, ultimately.

Karlin-Smith: Especially things like the provider tax, but even just the loss to certain health systems of Medicaid patients end up having a spiral effect where it may impact people who are on other health insurance, because these facilities will no longer have that funding to operate the way they are. Particularly some facilities talked about how the Obamacare Medicaid expansion really allowed them to expand their services and beef up. And now if they lose that population, you actually end up with risks of facilities closing. The Senate tried to provide a little bit of money to alleviate that, but I think that’s generally seen as quite small compared to the long-term effects of this bill.

Rovner: Yeah, there’s a $50 billion rural hospital slush fund, if you will, but that’s not going to offset $930 billion in cuts to Medicaid. And it’s important — I know we keep saying this, but it’s important to say again: It’s not just the people who will lose Medicaid who will be impacted, because if these facilities close — we’re talking about hospitals and rural clinics and other facilities that depend on Medicaid — people with all kinds of insurance are going to lack access. I see lots of nods going around.

Goldman: Yeah. One salient example that somebody told me earlier this week was, think about ER wait times. It already takes so long to get seen if you go into the ER. And when people don’t have health insurance, they’re seeking care at the ER because it’s an emergency and they waited until it was an emergency, or that’s just where they feel they can go. But this is going to increase ER wait times for everybody.

Rovner: And also, if nursing homes or other facilities close, people get backed up in the ER because they can’t move into the hospital when they need hospital care, because the hospital can’t discharge the people who are already there. I had sort of forgotten how that the crowded ERs are often a result of things other than too many people in the ER.

Goldman: Right.

Rovner: They’re a result of other strains on sort of the supply chain for care.

Goldman: There’s so many ripple effects and dominoes that are going to fall, if you will.

Rovner: So, there were some things that were in the House bill that, as predicted, didn’t make it into the Senate bill, because the parliamentarian said they violated the budget rules for reconciliation. That included the proposed Medicaid ban on all transgender care for minors and adults, and most of the cuts to states that use their own funds to cover undocumented people. But the parliamentarian ended up kind of splitting the difference on cutting funding to Planned Parenthood, which she had ruled in 2017 Congress couldn’t do in reconciliation. Alice, what happened here?

Ollstein: She decided that one year of cuts was OK, when they had originally sought 10. And the only reason they originally sought 10 is that’s how these bills work. It’s a 10-year budget window. That’s how you calculate things. They sort of meant it to function like a permanent defund. So, the anti-abortion movement was really divided on this outcome, where some were declaring it a big victory and some were saying: Oh, only one year. This is such a disappointment and not what we were promised blah, blah, blah. And it’ll be really interesting to see if even one year does function like a sort of permanent defund.

On the one hand, the anti-abortion movement is worried that because it’s one year, that means they’ll have to vote on it again next year right before the midterms, when people might get more squirrelly because of the politics of it, which obviously still exist now but would be more potent then. But clinics can’t survive without funding for long. We’re already seeing Planned Parenthoods around the country close because of Title X cuts, because of other budget instability. And so once a clinic closes, even if the funding comes back later, it can’t flip a switch and turn it back on. When things close, they close, the staff moves away, etc.

Rovner: And we should emphasize Medicaid has not been used to pay for federal abortion funding ever.

Ollstein: Yes. Yes.

Rovner: That’s part of the Hyde Amendment. So we’re talking about non-abortion services here. We’re talking about contraception, and STD testing and treatment, and cancer screenings, and other types of primary care that almost every Planned Parenthood provides. They don’t all provide abortion, but they all provide these other ancillary services that lots of Medicaid patients use.

Ollstein: Right. And so this will shut down clinics in states where abortion is legal, and it’ll shut down clinics in states where abortion is illegal and these clinics only are providing those other reproductive health services, which are already in scant supply and hard to come by. There’s massive maternity care deserts, contraceptive deserts around the country, and this is set to make that worse.

Rovner: So, while this bill was not painted as a repeal of the Affordable Care Act, unlike the 2017 version, it does do a lot to scale that law back. This has kind of flown under the radar. Maya, you wrote about this. What does this bill do to the ACA?

Goldman: Yeah. Well, so, there were a lot of changes that Congress was seeking to codify from rule that the Trump administration has finalized that really create a lot of extra barriers to enrolling in the ACA. A lot of those did not make it into the final bill that is being voted on, but there’s still more paperwork — death by paperwork. I think there’s preenrollment verification of eligibility, things like that. And I think just in general, the ACA has created massive gains in the insurer population in the United States over the last decade and a half. And there’s estimates that show that this would wipe out three-fourths of that gain. And so that’s just staggering to see that.

Rovner: Yeah. I think people have underestimated the impact that this could have on the ACA. Of course, we’ve talked about this also a million times. This bill does not extend the additional subsidies that were created under the Biden administration, which has basically doubled the number of people who’ve been able to afford coverage and bought it on the marketplaces. But I’ve seen estimates that more than half of the people could actually end up dropping out of ACA coverage.

Goldman: Yeah. And I think it’s important to talk about the timelines here. A lot of the work requirements in Medicaid won’t take effect for a couple of years, but people are going to lose their enhanced subsidies in January. And so we are going to see pretty immediate effects of this.

Rovner: And they’re shortening the enrollment time.

Goldman: Yeah.

Rovner: And people won’t be able to be auto-reenrolled, which is how a lot of people continue on their ACA coverage. There are a lot of little things that I think together add up to a whole lot for the ACA.

Goldman: Right. And Trump administration ACA enrollment barriers that were finalized might not be codified in this law, but they’re still finalized.

Rovner: Yeah.

Goldman: And so they will take effect for 2026 coverage.

Rovner: And while President Trump has said repeatedly that he didn’t want to touch Medicare, this bill ironically is going to do exactly that, because the amount the tax cuts add to the deficit is likely to trigger a Medicare sequester under budget rules. That means there will be automatic cuts to Medicare, probably as soon as next year.

All right, well, that is the moving bill, the One Big Beautiful Bill. One thing that has at least stopped moving for now is the Supreme Court, at least for the moment. The justices wrapped up their formal 2024-2025 term with some pretty significant health-related cases that impact two topics we’re talking about elsewhere in this episode, abortion and vaccines.

First, abortion. The court ruled that Medicaid patients don’t have the right to sue to enforce the section of Medicaid law that ensures free choice of provider. In this case, it frees South Carolina to kick Planned Parenthood out of its Medicaid program. Now, this isn’t about abortion. This is about, as we said, other services that Planned Parenthood provides. But, Alice, what are the ramifications of this ruling?

Ollstein: They could be very big. A lot of states have already tried and are likely to try to cut Planned Parenthood out of their Medicaid programs. And given this federal defund, this is now going after some of their remaining supports, which is state Medicaid programs, which is a separate revenue stream. And so this will just lead to even more clinic closures. And already, this kind of sexual health care is very hard to come by in a lot of places in the country. And that is set to be even more true in the future. And this is sort of the culmination of something that the right has worked towards for a long time. And so they had just a bunch of different strategies and tactics to go after Planned Parenthood in so many ways in the courts, and there’s still more shoes to drop. There’s still court cases pending.

There’s one in Texas that’s accusing Planned Parenthood of defrauding the state, and so that judgment could wipe them out even more. This federal legislative effort, there’s the Supreme Court case — and they’ve really been effective at just throwing everything at the wall and seeing what sticks. And enough is sticking now that the organization is really — they were able to beat back a lot of these attempts before. They were able to rally in Congress. They were able to rally at the state level to push back on a lot of this. And that wasn’t true this time. And so I don’t know what conclusion to take from that. There’s, obviously, people are very overwhelmed. There’s a lot going on. There are organizations getting hit left and right, and maybe this just got lost in the noise this time.

Rovner: Yeah, I think that may be. Well, the other big Supreme Court decision was one we’d talked about quite a bit, the so-called Braidwood case that was challenging the ability of the CDC’s [Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s] Preventive Services Task Force from recommending services that would then be covered by health insurance. This was arguably a win for the Biden administration. The court ruled that the task force members do not need to be confirmed by the Senate. But, Sarah, this also gives Secretary [Robert F.] Kennedy [Jr.] more power to do what he will with other advisory committees, right?

Karlin-Smith: Right. By affirming the way the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force was set up, in that the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] secretary is ultimately the authority for appointing the task force, which then makes recommendations around what coverage requirements under the ACA. It also sort of affirms the authority of the HHS secretary here. And I think people think it has implications for other bodies like CDC’s advisory committee on vaccines as well, where the secretary has a lot of authority.

So, I think people who really support the coverage advantages that have come through the USPSTF and Obamacare have always pushed for this outcome in this case. But given our current HHS secretary, there are some worries that it might lead to rollbacks or changes in areas of the health care paradigm that he does not support.

Rovner: Well, let us segue to that right now. That is, of course, as you mentioned, the other major CDC advisory committee, the one on immunization practices. When we left off, Secretary Kennedy had broken his promise to Senate health committee chairman Bill Cassidy and fired all 17 members of the committee, replacing them with vaccine skeptics and a couple of outright vaccine deniers. So last week, the newly reconstituted panel held its first meeting. How’d that go?

Karlin-Smith: It was definitely an interesting meeting, different, I think, for people who have watched ACIP [the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] in the past. Besides just getting rid of the members of the advisory panel, Kennedy also removed a lot of the CDC staff who work on that topic as well. So the CDC staffers who were there and doing their typical presentations were much smaller in number. And for the most part, I think they did a really good job of sticking to the tried-and-true science around these products and really having to grapple with extremely, I think, unusual questions from many of the panelists. But the agenda got shrunk quite a bit, and one of the topics was quite controversial. Basically, they decided to review the ingredient thimerosal, which was largely taken out of vaccines in the late ’90s, early 2000s, but remains in certain larger vials of flu vaccines.

Rovner: It’s a preservative, right? You need something in a multi-dose vaccine vial to keep it from getting contaminated.

Karlin-Smith: And they had a presentation from Lyn Redwood, who was a former leader of the Children’s Health Defense, which is a very anti-vax organization started by Robert Kennedy. The presentation was generally seen as not based in science and evidence, and there was no other presentations, and the committee voted to not really allow flu vaccines with that ingredient.

And the impact in the U.S. here is going to be pretty small because, I think, it’s about 4% of people get vaccines through those large-quantity vials, like if you’re in a nursing home or something like that. But what people are saying, and Scott Gottlieb [Food and Drug Administration commissioner in the first Trump administration] was talking a lot about this last week, was that this is really a hint of what is to come and the types of things they are going to take aim at. And he’s particularly concerned about another, what’s called an adjuvant, which is an ingredient added to vaccines to help make them work better, that’s in a lot of childhood vaccines, that Kennedy hinted at he wanted on the agenda for this meeting. It came off the agenda, but he presumes they will circle back to it. And if companies can’t use that ingredient in their vaccines, he’s not really clear they have anything else that is as good and as safe, and could force them out of the market.

So there were a bunch of hints of things concerning fights to come. The other big one was that they were saying they want to review the totality of the childhood vaccine schedule and the amount of vaccines kids get, which was really a red flag for people who followed the anti-vaccine movement, because anti-vaxxers have a lot of long-debunked claims that kids get too many vaccines, they get them too closer together. And scientists, again, have thoroughly debunked that, but they still push that.

Rovner: And that was something else that Kennedy promised Cassidy he wouldn’t mess with, if I recall correctly, right?

Karlin-Smith: You know, the nature of the agreement between Cassidy and Kennedy keeps getting more confusing to me. And I actually talked to both HHS’ secretary’s office and Cassidy’s office last week about that. And they both don’t actually agree on quite exactly what the terms were. But anyway, I looked at it in terms of the terms, like whether it’s to preserve the recommendations ACIP has made over time in the childhood schedule, whether it’s to preserve the committee members. I think it’s pretty clear that Kennedy has violated the sort of heart of the matter, which is he has gone after safe, effective vaccines and people’s access to vaccines in this country in ways that are likely to be problematic. And there are hints of more to come. He’s also cut off funding for vaccines globally. So, I don’t know. I almost just laugh thinking about what they actually agreed to, but there’s really no way Cassidy can say that Kennedy followed through on his promises.

Rovner: Well, meanwhile, even while ACIP was meeting last week, the HHS secretary was informing the members of Gavi, that’s the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations, that he was canceling the U.S.’ scheduled billion-dollar contribution because, he said, the public-private partnership that has vaccinated more than a billion children over the past two and a half decades doesn’t take vaccine safety seriously enough. Really?

Karlin-Smith: Yeah. Kennedy has these claims, again, that I think are, very clearly have been, debunked by experts, that Gavi is not thinking clearly about vaccine safety and offering vaccines they shouldn’t be, and the result is going to be huge gaps in what children can get around the globe to vaccines. And it comes on top of all the other cuts the U.S. has made recently to global health in terms of USAID [the U.S. Agency for International Development]. So I think these are going to be big impacts. And they may eventually trickle down to impact the U.S. in ways people don’t expect.

If you think about a virus like covid, which continues to evolve, one of the fears that people have always had is we get a variant that is, as it evolves, that is more dangerous to people and we’re less able to protect with the vaccines we have. If you allow the virus to kind of spread through unvaccinated communities because, say you weren’t providing these vaccines abroad, that increases the risk that we get a bad variant going on. So obviously, we should be concerned, I think, just about the millions of deaths people are saying this could cause globally, but there’s also impacts to our country as well and our health.

Rovner: I know there’s all this talk about soft-power humanitarian assistance and helping other countries, but as long as people can get on airplanes, it’s in our interest that people in other countries don’t get things that can be spread here, too, right?

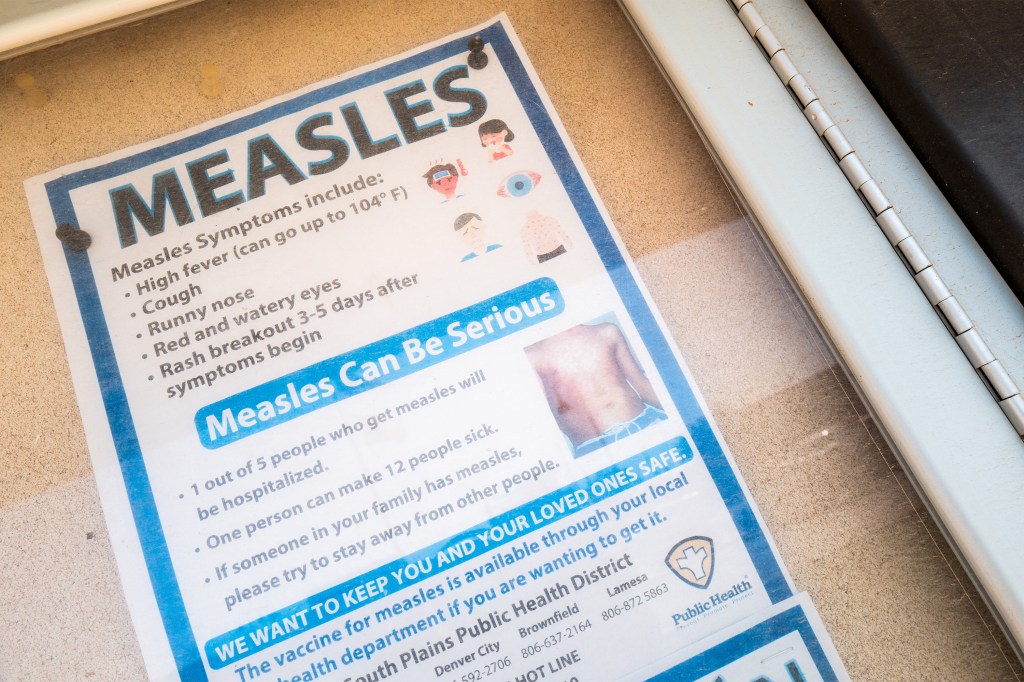

Goldman: Yeah. One very small comment that was made during the ACIP meeting this week from CDC staff was an update on the measles outbreak, which I just thought was interesting. They said that the outbreak in the South from earlier this year is mostly under control, but people are still bringing in measles from foreign countries. And so that’s very much a real, real threat.

Rovner: Yeah.

Ollstein: It’s the lesson that we just keep not learning again and again, which is if you allow diseases to spread anywhere, it’ll inevitably impact us here. We don’t live on an island. We have a very interconnected world. You can’t have a Well we’re going to only protect our people and nobody else mentality, because that’s just not how it works. And we’re reducing resources to vaccinate people here as well.

Rovner: That’s right. Turning back to abortion, there was other news on that front this week. In Wisconsin, the state Supreme Court formally overturned that state’s 1849 abortion ban. That was the big issue in the Supreme Court election earlier this year. But a couple of other stories caught my eye. One is from NBC News about how crisis pregnancy centers, those anti-abortion facilities that draw women in by offering free pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, are actually advising clinics against offering ultrasounds in some cases after a clinic settled a lawsuit for misdiagnosing a woman’s ectopic pregnancy, thus endangering her life. Alice, if this is a big part of the centers’ draw with these ultrasounds, what’s going on here?

Ollstein: I think it’s a good example. I want to stress that there’s a big variety of quality of medical care at these centers. Some have actual doctors and nurses on staff. Some don’t at all. Some offer good evidence-based care. Some do not. And I have heard from a lot of doctors that patients will come to them with ultrasounds that were incorrectly done or interpreted by crisis pregnancy centers. They were given wrong information about the gestation of their pregnancy, about the viability of their pregnancy. And so this doesn’t surprise me at all, based on what I’ve heard anecdotally.

People should also remember that these centers are not regulated as much as health clinics are. And that goes for things like HIPAA [the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act] as well. They don’t have the same privacy protections for the information people share there. And so I think we should also keep in mind that women might be depending more and more on these going forward as Planned Parenthoods close, as other clinics close because of all the cuts we just talked about. These clinics are really proliferating and are trying to fill that vacuum. And so things like this should keep people questioning the quality of care they provide.

Rovner: Yeah. And of course, layer on top of that the Medicaid cuts. There’s going to be an increased inability to get care, particularly in far-flung areas. You can sort of see how this can sort of all pile onto itself.

Well, the other story that grabbed me this week comes from the Pulitzer Prize-winning team at ProPublica. It’s an analysis of hospital data from Texas that suggests that the state’s total abortion ban is making it more likely that women experiencing early miscarriages may not be getting timely care, and thus are more likely to need blood transfusions or experience other complications. Anti-abortion groups continue to maintain that these bans don’t impact women with pregnancy complications, which are super common, for those who don’t know, particularly early in pregnancy. But experience continues to suggest that that is not the case.

Ollstein: Yeah. This is a follow-up to a lot of really good reporting ProPublica has done. They also showed that sepsis rates in Texas have gone way up in the wake of the abortion ban. And so anti-abortion groups like to point to the state’s report showing how many abortions are still happening in the state because of the medical emergency exceptions, and saying: See? It’s working. People are using the exceptions. And it is true that some people are, but I think that this kind of data shows that a lot of people are not. And again, if it’s with what I hear anecdotally, there’s just a lot of variety on the ground from hospital to hospital, even in the same city, interpreting the law differently. Their legal teams interpret what they can and can’t provide. It could depend on what resources they have. It could depend on whether they’re a public or private hospital, and whether they’re afraid of the state coming after them and their funding.

And so I think this shows that one doctor could say, Yes, I do feel comfortable doing this procedure to save this woman’s life, and another doctor could say, I’m going to wait and see. And then you get the sepsis, the hemorrhage. These are very sensitive situations when even a short delay could really be life-and-death, or be long-term health consequences. People have lost the ability to have more children. We’ve seen stories about that. We’ve seen stories about people having to suffer a lot of health consequences while their doctors figure out what kind of care they can provide.

Rovner: In the case of early miscarriage, the standard of care is to empty the uterus basically to make sure that the bleeding stops, which is either a D&C [dilation and curettage], which of course can also be an early abortion, or using the abortion pill mifepristone and misoprostol, which now apparently doctors are loath to use even in cases of miscarriage. I think that’s sort of the take-home of this story, which is a little bit scary because early miscarriage is really, really, really common.

Ollstein: Absolutely. And this is about the hospital context, which is obviously very important, but I’m also hearing that this is an issue even for outpatient care. So if somebody is having a miscarriage, it’s not severe enough that they have to be hospitalized, but they do need this medication to help it along. And when they go to the pharmacy, their prescription says, “missed abortion” or “spontaneous abortion,” which are the technical terms for miscarriage. But a pharmacist who isn’t aware of that, isn’t used to it, it’s not something they see all the time, they see that and they freak out and they say, Oh, I don’t want to get sued, so they don’t dispense the medication. Or there are delays. They need to call and double-check. And that has been causing a lot of turmoil as well.

Rovner: All right. Well, finally this week, Elon Musk is fighting with President Trump again over the budget reconciliation bill, but the long shadow of DOGE [the Department of Government Efficiency] still lives on in federal agencies. On the one hand, The Washington Post scooped this week that DOGE no longer has control over the Grants.gov website, which controls access to more than half a trillion dollars in federal grant funding. On the other hand, I’m still hearing that money is barely getting out and still has to get multiple approvals from political appointees before it can basically get to where it’s supposed to be going. NPR has a story this week with the ominous headline “‘Where’s Our Money?’ CDC Grant Funding Is Moving So Slowly Layoffs Are Happening.”

I know there’s so much other news happening right now, it’s easy to overlook, but I feel like the public health and health research infrastructure are getting starved to death while the rest of us are looking at shinier objects.

Goldman: Yeah. This the whole flood-the-zone strategy, right? There’s so many things going on that we can’t possibly keep up with all of them, but this is extremely important. I think if you talk to any research scientist that gets federal funding, they would tell you that things have not gotten back to normal. And there’s so much litigation moving through the courts that it’s going to take a really long time before this is settled, period.

Rovner: Yeah. We did see yet another court decision this week warning that the layoffs at HHS were illegal. But a lot of these layoffs happened so long ago that these people have found other jobs or put their houses up for sale. You can’t quite put this toothpaste back in the tube.

Goldman: Right. And also, with this particular ruling, this came from a Rhode Island federal judge, a Biden appointee, so it wasn’t very surprising. But it said that the reorganization plan of HHS was illegal. Or, not illegal, it was a temporary injunction on the reorganization plan and said HHS cannot place anyone else on administrative leave. But it doesn’t require them to rehire the employees that have been laid off, which is also interesting.

Rovner: Yeah. Well, we will continue to monitor that. All right, that is as much as this week’s news as we have time for. Now it’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s where we each recognize a story we read this week we think you should read, too. Don’t worry if you miss it. We will put the links in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Sarah, you were first to choose this week. Why don’t you go first?

Karlin-Smith: I took a look at a Wired piece from Will Bahr, “Snake Venom, Urine, and a Quest To Live Forever: Inside a Biohacking Conference Emboldened by MAHA.” And it is about a conference in Texas kind of designed to sell you products that they claim might help you live to 180 or more. A lot of what appears to be people essentially preying on people’s fears of mortality, aging, death to sell things that do not appear to be scientifically tested or validated by agencies like FDA. The founder even talks about using his own purified urine to treat his allergies. They’re microdosing snake venom. And it does seem like RFK is sort of emboldening this kind of way of thinking and behavior.

One of the things I felt was really interesting about the story is the author can’t quite pin down what unites all of these people in their interests in this space. In many cases, they claim there are sort of — there’s not a political element to it. But since I cover the pharma industry very closely, they all seem disappointed with mainstream medical systems and the pharma industry with the U.S., and they are seeking other avenues. But it’s quite an interesting look at the types of things they are willing to try to extend their lives.

Rovner: Yeah, it is quite the story. Maya, why don’t you go next?

Goldman: My extra credit this week is from my Axios colleague Tina Reed. It’s called “New Docs Get Schooled in Old Diseases as Vaxx Rates Fall.” And it’s all about how medical schools are adjusting their curriculum to teach students to spend more time on measles and things that we have considered to be wiped out in the United States. And I think it just — it really goes to show that this is something that is real and that’s actually happening. People are coming to emergency rooms and hospitals with these illnesses, and young doctors need to learn about them. We already have so many things to learn in medical school that there’s certainly a trade-off there.

Rovner: There is, indeed. And Alice, you have a related story.

Ollstein: Yes, I do. So, this is from The New York Times. It’s called “‘I Feel I’ve Been Lied To’: When a Measles Outbreak Hits Home,” by Eli Saslow. And it’s about the measles outbreak that originated in Texas. But what I think it does a really good job at is, we’ve talked a lot about how people have played up the dangers of vaccines and exaggerated them and, in some cases, outright lied about them, and how that’s influencing people, fear of autism, etc., fear of these adverse reactions. But I think this piece really shows that the other side of that coin is how much some of those same voices have downplayed measles and covid.

And so we have this situation where people are too afraid of the wrong things — vaccines — and not afraid enough of the right things — measles and these diseases. And so in the story people who are just, including people with some medical training, being shocked at how bad it is, at how healthy kids are really suffering and needing hospitalization and needing to be put on oxygen. And that really clashes with the message from this administration, which has really downplayed that and said it’s mainly hitting people who were already unhealthy or already had preexisting conditions, which is not true. It can hit other people. And so, yeah, I think it’s a very nuanced look at that.

Rovner: Yeah, it’s a really extraordinary story. My extra credit this week is from the medical journal The Lancet. And I won’t read the entire title or its multiple authors, because that would take the rest of the podcast. But I will summarize it by noting that it finds that funding provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development, which officially closed up shop this week after being basically illegally dissolved by the Trump administration, has saved more than 90 million lives over the past two decades. And if the cuts made this year are not restored, an additional 14 million people will die who might not have otherwise. Far from the Trump administration’s claims that USAID has little to show for its work, this study suggests that the agency has had an enormous impact in reducing deaths from HIV and AIDS, from malaria and other tropical diseases, as well as those other diseases afflicting less developed nations. We’ll have to see how much if any of those services will be maintained or restored.

OK. That’s this week’s show. Thanks to our editor, Emmarie Huetteman, and our producer-engineer, Francis Ying. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate it if you left us a review. That helps other people find us, too. Also, as always, you can email us your comments or questions. We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org. You can find me on X, @jrovner, or on Bluesky, @julierovner. Where are you guys these days? Sarah?

Karlin-Smith: I’m a little bit on X, mostly on Bluesky, at @SarahKarlin or @sarahkarlin-smith.

Rovner: Alice?

Ollstein: Mostly on Bluesky, @alicemiranda. Still a little bit on X, @AliceOllstein.

Rovner: Maya.

Goldman: I am on X, @mayagoldman_, and also on LinkedIn. You can just find me under my name.

Rovner: We will be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

2 weeks 6 days ago

Courts, Health Care Costs, Health Care Reform, Health Industry, Insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, Multimedia, Public Health, States, Abortion, CDC, KFF Health News' 'What The Health?', Legislation, Podcasts, reproductive health, Trump Administration, vaccines, Women's Health

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': RFK Jr. Upends Vaccine Policy, After Promising He Wouldn’t

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

After explicitly promising senators during his confirmation hearing that he would not interfere in scientific policy over which Americans should receive which vaccines, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. this week fired every member of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the group of experts who help the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention make those evidence-based judgments. Kennedy then appointed new members, including vaccine skeptics, prompting alarm from the broader medical community.

Meanwhile, over at the National Institutes of Health, some 300 employees — many using their full names — sent a letter of dissent to the agency’s director, Jay Bhattacharya, saying the administration’s policies “undermine the NIH mission, waste our public resources, and harm the health of Americans and people across the globe.”

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Anna Edney of Bloomberg News, Sarah Karlin-Smith of the Pink Sheet, and Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico Magazine.

Panelists

Anna Edney

Bloomberg News

Sarah Karlin-Smith

Pink Sheet

@sarahkarlin-smith.bsky.social

Joanne Kenen

Johns Hopkins University and Politico

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- After removing all 17 members of the vaccine advisory committee, Kennedy on Wednesday announced eight picks to replace them — several of whom lack the expertise to vet vaccine research and at least a couple who have spoken out against vaccines. Meanwhile, Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, the Republican head of the chamber’s health committee, has said little, despite the fact that Kennedy’s actions violate a promise he made to Cassidy during his confirmation hearing not to touch the vaccine panel.

- In other vaccine news, the Department of Health and Human Services has canceled private-sector contracts exploring the use of mRNA technology in developing vaccines for bird flu and HIV. The move raises concerns about the nation’s readiness against developing and potentially devastating health threats.

- Hundreds of NIH employees took the striking step of signing a letter known as the “Bethesda Declaration,” protesting Trump administration policies that they say undermine the agency’s resources and mission. It is rare for federal workers to use their own names to voice public objections to an administration, let alone President Donald Trump’s, signaling the seriousness of their concerns.

- Lawmakers have been considering adding Medicare changes to the tax-and-spend budget reconciliation legislation now before the Senate — specifically, targeting the use of what’s known as “upcoding.” Curtailing the practice, through which medical providers effectively inflate diagnoses and procedures to charge more, has bipartisan support and could increase the savings by reducing the amount the government pays for care.

Also this week, Rovner interviews Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum and former director of the Congressional Budget Office, to discuss how the CBO works and why it’s so controversial.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: Stat’s “Lawmakers Lobby Doctors To Keep Quiet — or Speak Up — on Medicaid Cuts in Trump’s Tax Bill,” by Daniel Payne.

Anna Edney: KFF Health News’ “Two Patients Faced Chemo. The One Who Survived Demanded a Test To See if It Was Safe,” by Arthur Allen.

Sarah Karlin-Smith: Wired’s “The Bleach Community Is Ready for RFK Jr. To Make Their Dreams Come True,” by David Gilbert.

Joanne Kenen: ProPublica’s “DOGE Developed Error-Prone AI Tool To ‘Munch’ Veterans Affairs Contracts,” by Brandon Roberts, Vernal Coleman, and Eric Umansky.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- The Hill’s “Cassidy in a Bind as RFK Jr. Blows Up Vaccine Policy,” by Nathaniel Weixel.

- JAMA Pediatrics’ “Firearm Laws and Pediatric Mortality in the US,” by Jeremy Samuel Faust, Ji Chen, and Shriya Bhat.

Click to open the transcript

Transcript: RFK Jr. Upends Vaccine Policy, After Promising He Wouldn’t

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, June 12, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via videoconference by Anna Edney of Bloomberg News.

Anna Edney: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico Magazine.

Joanne Kenen: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: And Sarah Karlin-Smith of the Pink Sheet.

Sarah Karlin-Smith: Hello, everybody.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have my interview with Douglas Holtz-Eakin, head of the American Action Forum and former head of the Congressional Budget Office. Doug will talk about what it is that CBO actually does and why it’s the subject of so many slings and arrows. But first, this week’s news.

The biggest health news this week is out of the Department of Health and Human Services, where Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on Monday summarily fired all 17 members of the CDC’s [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s] vaccine advisory committee, something he expressly promised Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy he wouldn’t do, in exchange for Cassidy’s vote to confirm him last winter. Sarah, remind us what this committee does and why it matters who’s on it?

Karlin-Smith: So, they’re a committee that advises CDC on who should use various vaccines approved in the U.S., and their recommendations translate, assuming they’re accepted by the CDC, to whether vaccines are covered by most insurance plans and also reimbursed. There’s various laws that we have that set out, that require coverage of vaccines recommended by the ACIP [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] and so forth. So without ACIP recommendations, you may — vaccines could be available in the U.S. but extremely unaffordable for many people.

Rovner: Right, because they’ll be uncovered.

Karlin-Smith: Correct. Your insurance company may choose not to reimburse them.

Rovner: And just to be clear, this is separate from the FDA’s [Food and Drug Administration’s] actual approval of the vaccines and the acknowledgment it’s safe and effective. Right, Anna?

Edney: Yeah, there are two different roles here. So the FDA looks at all the safety and effectiveness data and decides whether it’s safe to come to market. And with ACIP, they are deciding whether these are things that children or adults or pregnant women, different categories of people, should be getting on a regular basis.

Rovner: So Wednesday afternoon, Secretary Kennedy named eight replacements to the committee, including several with known anti-vaccine views. I suppose that’s what we all expected, kind of?

Kenen: He also shrunk it, so there are fewer voices. The old panel, I believe, had 17. And the law says it has to have at least eight, and he appointed eight. As far as we know, that’s all he’s appointing. But who knows? A couple of more could straggle in. But as of now, it means there’s less viewpoints, less voices, which may or might not turn out to be a good thing. But it is a different committee in every respect.

Edney: And I think it is a bit of what we expected in the sense that these are people who either are outright vaccine critics or, in a case or two, have actually said vaccines do horrible things to people. One of them had said before that the covid vaccine caused an AIDS-like virus in people. And there is a nurse that is part of the committee now that said her son was harmed by vaccines. And not saying that is or isn’t true — her concerns could be valid — but that she very much has worked to question vaccines.

So I think it is the committee that we maybe would’ve expected from a sense of, I think he’s trying to bring in people who are a little bit mainstream, in the sense if you looked at where they worked or things like that, you might not say, like: Oh, Georgetown University. I get it. But they are people who have taken kind of the more of a fringe approach within maybe kind of a mainstream world.

Karlin-Smith: I was going to say there’s also many people on the list that it’s just not even clear to me why you would look at their expertise and think, Oh, this is a committee they should serve on. One of the people is an MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], essentially, like, business school professor who tangentially I think has worked on health policy to some extent. But, right, this is not somebody who has extreme expertise in vaccinology, immunology, and so forth. You have a psychiatrist whose expertise seems to be on nutrition and brain health.

And one thing I think people don’t always appreciate about this committee at CDC is, you see them in these public meetings that happen a few times a year, but they do a lot of work behind the scenes to actually go through data and make these recommendations. And so having less people and having people that don’t actually have the expertise to do this work seems like it could cause a big problem just from that point of view.

Edney: And that can be the issue that comes up when Kennedy has said, I don’t want anyone with any conflicts of interest. Well, we’ve talked about this. Certainly you don’t want a legit conflict of interest, but a lot of people who are going to have the expertise you need may have a perceived conflict that he doesn’t want on there. So you end up maybe with somebody who works in operations instead of on vaccines.

Rovner: You mean maybe we’ll have people who actually have researched vaccines.

Edney: Right. Exactly. Yeah.

Kenen: The MIT guy is an expert in supply chains. None of us know who the best supply chain business school professor is in the world. Maybe it’s him, but it’s a very odd placement.

Rovner: Well, so far Sen. Cassidy hasn’t said very much other than to kind of communicate that he’s not happy right now. Has anybody heard anything further? The secretary has been sort of walking up to the line of things he told the senator he wouldn’t do, but this clearly is over the line of things he told the senator he wouldn’t do. And now it’s done.

Kenen: It’s like over the line and he set fire to it. And Cassidy has been pretty quiet. And in fact, when Kennedy testified before Cassidy — Cassidy is the chairman of the health committee — a couple of weeks ago, he gave him a really warm greeting and thanked him for coming and didn’t say: You’re a month late. I wanted you here last month. The questions were very soft. And things have only gotten more heated since then, with the dissolution of the ACIP committee and this reconstitution of it. And he’s been very quiet for somebody who publicly justified, who publicly wrestled with this, the confirmation, was the deciding vote, and then has been really soft since then — in public.

Rovner: I sent around a story this morning to the panelists, from The Hill, which I will link to in the show notes, that quotes a political science professor in Louisiana pointing out that perhaps it would be better for Cassidy politically not to say anything, that perhaps public opinion among Republicans who will vote in a primary is more on the side of Secretary Kennedy than Sen. Cassidy, which raises some interesting questions.

Edney: Yeah. And I think that, at least for me, I’m at the point of wondering if Cassidy didn’t know that all along, that there’s a point he was willing to go up to but a line that he is never going to have been willing to cross, and that is actually coming out against Kennedy and, therefore, [President Donald] Trump. He doesn’t want to lose his reelection. I am starting to wonder if he just hoped it wouldn’t come to this and so was able to say those things that got him to vote for Kennedy and then hope that it wouldn’t happen.

And I think that was a lot of people. They weren’t on the line like Cassidy was, but I think a lot of people thought, Oh, nothing’s ever going to happen on this. And I think another thing I’m learning as I cover this administration and the Kennedy HHS is when they say, Don’t worry about it, look away, we’re not doing anything that big of a deal, that’s when you have to worry about it. And when they make a big deal about some policy they’re bringing up, it actually means they’re not really doing a lot on it. So I think we’re seeing that with vaccines for sure.

Rovner: Yes, classic watch what they do not what they say.

Kenen: But if you’re Cassidy and you already voted to impeach President Trump, which means you already have a target from the right — he’s a conservative, but it’s from the more conservative, though, the more MAGA [Make America Great Again] — if you do something mavericky, sometimes the best political line is to continue doing it. But they’ve also changed the voting rules, my understanding is, in Louisiana so that independents are — they used to be able to cross party lines in the primaries, and I believe you can’t do that anymore. So that also changed, and that’s recent, so that might have been what he thought might save him.

Rovner: Well, it’s not just ACIP where Secretary Kennedy is insinuating himself directly into vaccine policy. HHS has also canceled a huge contract with vaccine maker Moderna, which was working on an mRNA-based bird flu vaccine, which we might well need in the near future, and they’ve also canceled trials of potential HIV vaccines. What do we know about what this HHS is doing in terms of vaccine policy?

Karlin-Smith: The bird flu contract I think is very concerning because it seems to go along the lines of many people in this administration and Kennedy’s orbit who sometimes might seem a little bit OK with vaccines, more OK than Kennedy’s record, is they are very anti the newer mRNA technology, which we know proved very effective in saving tens of millions of lives. I was looking at some data just even the first year they rolled out after covid. So we know they work. Obviously, like all medical interventions, there are some side effects. But again, the benefits outweigh the risks. And this is the only, really, technology that we have that could really get us vaccines really quickly in a pandemic and bird flu.

Really, the fear there is that if it were to jump to humans and really spread from human-to-human transmission — we have had some cases recently — it could be much more devastating than a pandemic like covid. And so not having the government have these relationships with companies who could produce products at a particular speed would be probably incredibly devastating, given the other technologies we have to invest in.

Edney: I think Kennedy has also showed us that he, and spoken about this, is that he is much more interested in a cure for anything. He has talked about measles and Why can’t we just treat it better? And we’re seeing that with the HIV vaccine that won’t be going forward in the same way, is that the administration has basically said: We have the tools to deal with it if somebody gets it. We’re just not going to worry about vaccinating as much. And so I think that this is a little bit in that vein as well.

Rovner: So the heck with prevention, basically.

Edney: Exactly.

Rovner: Well, in related news, some 300 employees of the National Institutes of Health, including several institute directors, this week sent an open letter of dissent to NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya that they are calling the “Bethesda Declaration.” That’s a reference to the “Great Barrington Declaration” that the NIH director helped spearhead back in 2020 that protested covid lockdowns and NIH’s handling of the science.

The Bethesda Declaration protests policies that the signatories say, quote, “undermine the NIH mission, waste our public resources, and harm the health of Americans and people across the globe.” Here’s how one of the signers, Jenna Norton of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, put it in a YouTube video.

Jenna Norton: And the NIH that I’m working in now is unrecognizable to me. Every day I go into the office and I wonder what ethical boundary I’m going to be asked to violate, what probably illegal action am I going to be asked to take. And it’s just soul-crushing. And that’s one of the reasons that I’m signing this letter. One of my co-signers said this, but I’m going to quote them because I thought it was so powerful: “You get another job, but you cannot get another soul.”

Rovner: I’ve been covering NIH for a lot of years. I can’t remember pushback like this against an administration by its own scientists, even during the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. How serious is this? And is it likely to have any impact on policy going forward?

Edney: I think if you’re seeing a good amount of these signers who sign their actual names and if you’re seeing that in the government, something is very serious and there are huge concerns, I think, because, as a journalist, I try to reach people who work in the government all the time. And if they’re not in the press office, if they speak to me, which is rare, even they do not want me to use their name. They do not want to be identified in any way, because there are repercussions for that.

And especially with this administration, I’m sure that there is some fear for people’s jobs and in some instances maybe even beyond. But I think that whether there will be any policy changes, that is a little less clear, how this administration might take that to heart or listen to what they’re saying.

Rovner: Bhattacharya was in front of a Senate Appropriations subcommittee this week and was asked about it, but only sort of tangentially. I was a little bit surprised that — obviously, Republicans, we just talked about Sen. Cassidy, they are afraid to go up against the Trump administration’s choices for some of these jobs — but I was surprised that even some of the Democrats seemed a little bit hands-off.

Edney: Yeah, no one ever asks the questions I want asked at hearings, I have to say. I’m always screaming. Yeah, exactly. I’m always like: No. What are you doing?

Rovner: That’s exactly how I was, like: No, ask him this.

Edney: Right.

Rovner: Don’t ask him that.

Edney: Exactly.

Rovner: Well, moving on to the Big Budget Bill, which is my new name for it. Everybody else seems to have a different one. It’s still not clear when the Senate will actually take up its parts, particularly those related to health, but it is clear that it’s not just Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act on the table but now Medicare, too. Ironically, it feels like lawmakers could more easily squeeze savings out of Medicare without hurting beneficiaries than either Medicaid or the ACA, or is that just me being too simplistic about this whole thing?

Kenen: The Medicare bill is targeted at upcoding, which means insurers or providers sort of describing a symptom or an illness in the most severe terms possible and they get paid more. And everybody in government is actually against that. Everybody ends up paying more. I don’t know what else the small —this has just bubbled up — but I don’t know if there’s other small print.

This alone, if it wasn’t tied to all the politics of everything else in this bill, this is the kind of thing, if you really do a bill that attacks inflated medical bills, you could probably get bipartisan support for. But because — and, again, I don’t know what else is in, and I know that’s the top line. There may be something that I’m not aware of that is more of a poison pill. But that issue you could get bipartisan consensus on.

But it’s folded into this horrendously contentious thing. And it’s easy to say, Oh, they’re trying to cut Medicare, which in this case maybe they’re trying to cut it in a way that is smart, but it just makes it more complicated. If they do go for it, if they do decide that this goes in there, it could create a little more wiggle room to not cut some other things quite as deeply.

But again, they’re calling everything waste, fraud, and abuse. None of us would say there is no waste, fraud, and abuse in government or in health care. We all know there is waste, fraud, and abuse, but that doesn’t mean that what they’re cutting here is waste, fraud, and abuse in other aspects of that bill.

Rovner: Although, as you say, I think there’s bipartisan consensus, including from Mehmet Oz, who runs Medicare, that upcoding is waste and fraud.

Kenen: Right. But other things in the bill are being called waste, fraud, and abuse that are not, right? That there’s things in Medicaid that are not waste, fraud, and abuse. They’re just changing the rules. But I agree with you, Julie. I think that in a bill that is not so fraught, it would’ve been easier to get consensus on this particular item, assuming it’s a clean upcoding bill, if you did it in a different way.

Rovner: And also, there’s already a bipartisan bill on pharmacy benefit managers kicking around. There are a lot of things that Congress could do on a bipartisan basis to reduce the cost of Medicare and make the program better and shore it up, and that doesn’t seem to be what’s happening, for the most part.

Well, we continue to learn things about the House-passed bill that we didn’t know before, and one thing we learned this week that I think bears discussing comes from a new poll from our KFF polling unit that found that nearly half those who purchased Affordable Care Act coverage from the marketplaces are Republicans, including a significant percentage who identify themselves as MAGA Republicans.

So it’s not just Republicans in the Medicaid expansion population who’d be impacted. Millions of Trump supporters could end up losing or being priced out of their ACA insurance, too, particularly in non-Medicaid-expansion states like Florida and Texas. A separate poll from Quinnipiac this week finds that only 27% of respondents think Congress should pass the big budget reconciliation bill. Could either of these things change some Republican perceptions of things in this bill, or is it just too far down the train tracks at this point?

Karlin-Smith: We saw a few weeks ago [Sen.] Joni Ernst seemed to be really highly critical of her own supporters who were pushing back on her support for the bill. Even when Republicans failed to get rid of the ACA and [Sen.] John McCain gave it the thumbs-down, he was the one. It wasn’t like everyone else was coming to help him with that.

And again, I think there was the same dynamic where a lot of people who, if you had asked them did they support Obamacare while it was being written in law, in early days before they saw any benefit of it, would have said no and politically align themselves with the Republican Party, and their views have come to realize, once you get a benefit, that it may actually be more desirable, perhaps, than you initially thought.

I think it could become a problem for them, but I don’t think it’s going to be a mass group of Republicans are going to change their minds over this.

Rovner: Or are they going to figure out that that’s why they’re losing their coverage?

Kenen: Right. Many things in this bill, if it goes into effect, are actually after the 2026 elections. The ACA stuff is earlier. And someone correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m pretty sure it expires in time for the next enrollment season.

Rovner: Yeah, and we’ve talked about this before. The expanded credits, which are not sort of quote-unquote—

Kenen: No, they’re separate.

Rovner: —“in this bill,” but it’s the expiration of those that’s going to cause—

Kenen: In September. And so those—

Rovner: Right.

Kenen: —people would—

Rovner: In December. No, at the end of the year they expire.

Kenen: Right. So that in 2026, people getting the expanded benefit. And there’s also somewhat of a misunderstanding that that legislation opened Obamacare subsidies to people further up the eligibility roof, so more people who had more money but still couldn’t afford insurance do get subsidies. That goes away, but it cascades down. It affects lower-income people. It affects other people. It’s not just that income bracket.

There are sort of ripple effects through the entire subsidized population. So people will lose their coverage. There’s really no dispute about that. The reason it was sunsetted is because it costs money. Congress does that a lot. If we do it for five years, we can get it on the score that we need out of the CBO. But if we do it for 10 years, we can’t. So that is not an unusual practice in Congress for Republicans and Democrats, but that happens before the election.

It’s just whether people connect the dots and whether there are enough of them to make a difference in an election, right? Millions of people across the country. But does it change how people vote in a specific race in a state that’s already red? If it’s a very red state, it may not make people get mad, but it may not affect who gets elected to House or the Senate in 2026.

Rovner: We will see. So Sarah, I was glad you mentioned Sen. Ernst, because last week we talked about her comment that we’re all going to die, in response to complaints at a town hall meeting about the Medicaid cuts. Well, Medicare and Medicaid chief Mehmet Oz says to Sen. Ernst, Hold my beer. Speaking on Fox Business, Oz said people should only get Medicaid if they, quote, “prove that they matter.”

Now, this was in the context of saying that if you want Medicaid, you should work or go to school. Of course, most people on Medicaid do work or care-give for someone who can’t work or do go to school — they just have jobs that don’t come with private health insurance. I can’t help but think this is kind of a big hole in the Republican talking points that we keep seeing. These members keep suggesting that all working people or people going to school get health insurance, and that’s just not the case.

Kenen: But it sounds good.

Karlin-Smith: I was going to say, there are small employers that don’t have to provide coverage under the ACA. There are people that have sort of churned because they work part time or can’t quite get enough hours to qualify, and these are often lower-income people. And I think the other thing I’ve seen people, especially in the disability committee and so forth, raises — there’s an underlying rhetoric here that to get health care, you have to be deserving and to be working.

That, I think, is starting to raise concerns, because even though they kind of say they’re not attacking that population that gets Medicaid, I think there is some concern about the language that they’re using is placing a value on people’s lives that just sort of undermines those that legitimately cannot work, for no fault of their own.

Kenen: It’s how the Republicans have begun talking about Medicaid again. Public opinion, and KFF has had some really interesting polls on this over the last few years, really interesting changes in public attitudes toward Medicaid, much more popular. And it’s thought of even by many Republicans as a health care program, not a welfare program. What you have seen — and that’s a change.

What you’ve seen in the last couple of months is Republican leaders, notably Speaker [Mike] Johnson, really talking about this as welfare. And it’s very reminiscent of the Reagan years, the concept of the deserving poor that goes back decades. But we haven’t heard it as much that these are the people who deserve our help and these are the lazy bums or the cheats.

Speaker Johnson didn’t call them lazy bums and cheats, but there’s this concept of some people deserve our help and the rest of them, tough luck. They don’t deserve it. And so that’s a change in the rhetoric. And talking about waste and talking about fraud and talking about abuse is creating the impression that it’s rampant, that there’s this huge abuse, and that’s not the case. People are vetted for Medicaid and they do qualify for Medicaid.

States have their own money and their own enrollment systems. They have every incentive to not cover people who don’t deserve to be covered. Again, none of us are saying there’s zero waste. We would never say that. None of us are saying there’s zero abuse. But it’s not like that’s the defining characteristic of Medicaid is that it’s all fraud and abuse, and that you can cut hundreds of millions of dollars out of it without anybody feeling any pain.

Rovner: And there were a lot of Republican states that expanded Medicaid, even when they didn’t have to, that are going to feel this. That’s a whole other issue that I think we will talk about probably in the weeks to come. I want to move to DOGE [the Department of Government Efficiency]. Elon Musk is back in California, having had a very ugly breakup with President Trump and possibly a partial reconciliation. But the impact of DOGE continues across the federal government, as well as at HHS.

The latest news is apparently hundreds of CDC employees who were told that they were being laid off who are now being told: Never mind. Come back to work. Of course, this news comes weeks after they were told they were being fired, and it’s unclear how many of them have upended their work and family lives in the interim.

But at the same time, much of the money that’s supposed to be flowing, appropriations for the current fiscal year that were passed by Congress and signed by President Trump — apparently still being held up. What are you guys hearing about how things at HHS are or aren’t going in the wake of the DOGE cutbacks? Go ahead, Sarah.

Karlin-Smith: It still seems like people at the federal government that I talked to are incredibly unhappy. At other agencies, as well, there have been groups of people called back to work, including at FDA. But still, I think the general sense is there’s a lot of chaos. People aren’t comfortable that their job will be there long-term. Many people even who were called back are saying they’re still looking for work other places.

There’s just so many changes in both, I think, in their day-to-day lives and how they do their job, but then also philosophically in terms of policy and what they are allowed to do, that I think a lot of people are becoming kind of demoralized and trying to figure out: Can they do what they signed up to do in their job, or is it better just to move on? And I think there’s going to be long-term consequences for a lot of these government agencies.

Rovner: You mean being fired and unfired and refired doesn’t make for a happy workplace?

Karlin-Smith: I was going to say a lot of them were called back to offices that they didn’t always have to come to. They’ve lost people who have been working and never lost their jobs, have lost close colleagues, support staff they rely on to do their jobs. So it’s really complicated even if you’re in the best-case scenario, I think, at a lot of these agencies.

Kenen: And a loss of institutional memory, too, because nobody knows everything in your office. And in an office that functions, it’s collaborative. I know this, you know that. We work together, and we come out with a better product. So that’s been eviscerated. And then — we’re all in a part of an industry that’s seen a lot of downsizing and chaos, in journalism, and the outcome is worse. When things get beaten up and battered and kicked out, things are harmed. And it’s true of any industry, since we haven’t been AI-replaced yet.

Rovner: Yet. So it’s been a while since we had a, quote, “This Week in Private Equity in Health Care,” but this week the governor of Oregon signed into law a pretty serious ban on private equity ownership of physician practices. Apparently, this was prompted by the purchase by Optum — that’s the arm of UnitedHealth that is now the largest owner of physician practices in the U.S. — of a multi-specialty group in Eugene, Oregon, that caused significant dislocation for patients and was charged by the state with impermissibly raising prices. Hospitals are not included in Oregon’s ban, but I wonder if this is the start of a trend. Or is this a one-off in a pretty blue state, which Oregon is?

Edney: I think that it could be. I don’t know, certainly, but I think to watch how it plays out might be quite interesting. The problem with private equity ownership of these doctors’ offices is then the doctors don’t feel that they can actually give good care. They’ve got to move people through. It’s all about how much money can they make or save so that private equity can get its reward. And so I think that people certainly are frustrated by it, as in people who get the care, also people who are doing legislating and things like that. So I wouldn’t be surprised to see some other attempts at this pop up now that we’ve seen one.

Kenen: But Oregon is uniquely placed to get something like this through. They are a very blue state. They’ve got a history of some health reform stuff that’s progressive. I don’t think you’ll see this domino-ing through every state legislature in the short term.

Rovner: But I will also say that even in Oregon, it took a while to get this through. There was a lot of pushback because there is concern that without private equity, maybe some of these practices are going to go belly up. This is the continuing fight about the future of the health care workforce and who’s going to underwrite it.

Well, finally this week, I want to give a shoutout to the biggest cause of childhood death and injury that is not being currently addressed by HHS, which is gun violence. According to a new study in JAMA Pediatrics, firearms deaths among children and teens grew significantly in states that loosened gun laws following a major Supreme Court decision in 2010. And it wasn’t just accidents. The increase in deaths included homicides and suicides, too. Yet gun violence seems to have kind of disappeared from the national agenda for both parties.

Edney: Yeah, you don’t hear as much about it. I don’t know why. I don’t know if it’s because we’re inundated every day with a million things. And currently at the moment, that just hasn’t come up again, as far as a tragedy. That often tends to bring it back to people’s front of mind. And I think that there is, on the Republican side at least, we’re seeing tax cuts for gun silencers and things like that. So I think they’re emboldened on the side of NRA [the National Rifle Association]. I don’t know if Democrats are seeing that and thinking it’s a losing battle. What else can I focus my attention on?

Kenen: Well, it’s in the news when there’s a mass killing. Society has just sort of become inured or shut its eyes to the day to day to day to day to day. The accidents, the murders. Don’t forget, a lot of our suicide problem is guns, including older white men in rural states who are very pro-gun. Those who kill themselves, it is how they kill themselves. It’s just something we have let happen.

Rovner: Plus, we’re now back to arguing about whether or not vaccines are worthwhile. So, a lot of the oxygen is being taken up with other issues at the moment.

Kenen: There’s a very overcrowded bandwidth these days. Yes.

Rovner: There is. I think that’s fair. All right, well, that is this week’s news, or as much as we could squeeze in. Now we will play my interview with Doug Holtz-Eakin, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am so pleased to welcome to the podcast Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank, and former head of the Congressional Budget Office during the George W. Bush administration, when Republicans also controlled both Houses of Congress. Doug, thank you so much for being here.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin: My pleasure. Thank you.

Rovner: I mostly asked you here to talk about CBO and what it does and why it’s so controversial. But first, tell us about the American Action Forum and what it is you do now.

Holtz-Eakin: So the American Action Forum is, on paper, a center-right think tank, a 501(c)(3) entity that does public education on policy issues, but it’s modeled on my experiences at working at the White House twice, running the Congressional Budget Office, and I was also director of domestic and economic policy on the John McCain campaign. And in those jobs, you worked on policy issues. You did policy education, issues, options, advice, but you worked on whatever was happening that day.

You didn’t have the luxury of saying: Yeah, that’s not what I do. Get back to me when something interests you. And you had to convey your results in English to nonspecialists. So there was a sort of a premium on the communications function, and you also had to understand the politics. On a campaign you had to make good policy good politics, and at the White House you worried about the president’s program.

No matter who was in Congress, that was all they thought about. And in Congress, the CBO is nonpartisan by law, and so obviously you have to care about that. And I just decided I like that work, and that’s what AAF does. We do domestic and economic policy on the issues that are going on in Congress or the agencies, with an emphasis on providing material that is readable to nonspecialists so they can understand what’s going on.

Rovner: You’re a professional policy nerd, in other words.

Holtz-Eakin: Pretty much, yeah.

Rovner: As am I. So I don’t mean that in any way to be derogatory. I plead guilty myself.

Holtz-Eakin: These bills, who knew?