Innovation Doesn’t Always Have To Involve The Latest Tech, MD Anderson Exec Says

While adopting new technology is obviously a big part of healthcare innovation teams’ work, there are plenty of worthwhile initiatives that don’t involve advanced technologies, pointed out Dan Shoenthal, chief innovation officer at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

While adopting new technology is obviously a big part of healthcare innovation teams’ work, there are plenty of worthwhile initiatives that don’t involve advanced technologies, pointed out Dan Shoenthal, chief innovation officer at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The post Innovation Doesn’t Always Have To Involve The Latest Tech, MD Anderson Exec Says appeared first on MedCity News.

1 year 5 months ago

Health Tech, Hospitals, Providers, Cancer, innovation, MD Anderson, MD Anderson Cancer Center, patient experience, Reuters Events, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Opinion: Colorectal cancer is increasing among young people. It’s time to boost research on it

I am not writing here to talk about my husband, Chadwick Boseman, who died far too young from colorectal cancer. I am not here to give any glimpses into our obviously private life and his obviously private battle with this cancer, which is affecting far more young lives than it should.

The legacy he created is not about cancer and I hope you don’t remember him that way. Instead, remember him for his work. Remember him as Chadwick Boseman the actor, the writer, the leader, the inspiration.

1 year 5 months ago

First Opinion, Cancer, Research

AI could predict whether cancer treatments will work, experts say: ‘Exciting time in medicine'

A chemotherapy alternative called immunotherapy is showing promise in treating cancer — and a new artificial intelligence tool could help ensure that patients have the best possible experience.

A chemotherapy alternative called immunotherapy is showing promise in treating cancer — and a new artificial intelligence tool could help ensure that patients have the best possible experience.

Immunotherapy, first approved in 2011, uses the cancer patient’s own immune system to target and fight cancer.

While it doesn’t work for everyone, for the 15% to 20% who do see results, it can be life-saving.

WHAT IS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)?

Like any medication, immunotherapy has the potential for adverse side effects — which can be severe for some.

Studies show that some 10% to 15% of patients develop "significant toxicities."

Headquartered in Chicago, GE HealthCare — working in tandem with Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) in Nashville, Tennessee — has created an AI model that's designed to help remove some of the uncertainties surrounding immunotherapy.

Over the five years it’s been in development, the AI model was trained on thousands of patients’ electronic health records (EHRs) to recognize patterns in how they responded to immunotherapy, focusing on safety and effectiveness.

AI MODEL COULD HELP PREDICT LUNG CANCER RISKS IN NON-SMOKERS, STUDY FINDS: ‘SIGNIFICANT ADVANCEMENT’

"The model predicts which patients are likely to derive the benefit from immunotherapy versus those patients who may not," said Jan Wolber, global digital product leader at GE HealthCare’s pharmaceutical diagnostics segment, in an interview with Fox News Digital.

"It also predicts which patients have a likelihood of developing one or more significant toxicities."

When pulling data from the patient’s health record, the model looks at demographic information, preexisting diagnoses, lifestyle habits (such as smoking), medication history and more.

"All of these data are already being collected by the patient’s oncologist, or they’re filling out a form in the waiting room ahead of time," said Travis Osterman, a medical oncologist and associate chief medical information officer at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in an interview with Fox News Digital.

(Osterman is working with Wolber on the development of the AI model.)

BREAST CANCER BREAKTHROUGH: AI PREDICTS A THIRD OF CASES PRIOR TO DIAGNOSIS IN MAMMOGRAPHY STUDY

"We're not asking for additional blood samples or complex imaging. These are all data points that we're already collecting — vital signs, diagnoses, lab values, those sorts of things."

In a study, the AI model showed 70% to 80% accuracy in predicting patients’ responses to immunotherapies, according to an article published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology Clinical Cancer Informatics.

"While the models are not perfect, this is actually a very good result," Wolber said. "We can implement those models with very little additional effort because there are no additional measurements required in the clinic."

This type of technology is "a natural progression of what we've been doing in medicine for a very long time," Osterman said.

"The only difference is, instead of surveying patients, we're taking the entirety of the medical record and looking for risk factors that contribute to an outcome," he said in an interview with Fox News Digital.

With immunotherapy, there is generally a lower response rate than with chemotherapy, Osterman noted — but some patients have "incredible responses" and ultimately become cancer-free.

"I would be horrified to know that one of my patients that I didn't give immunotherapy to could have been one of the tremendous responders," he told Fox News Digital.

Conversely, Osterman noted that in rare cases, immunotherapy can have some serious side effects.

"I would say about half of patients don't have any side effects, but for those who do, some of them are really life-altering," he said.

"We don't want to miss anyone, but we also don't want to harm anyone."

At the core of the AI project, Osterman said, is the ability to "put all the information into the exam room," so the oncologist can counsel the patient about the risks and benefits of this particular therapy and make the best, most informed decision about their care.

Dr. Marc Siegel, clinical professor of medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center and a Fox News medical contributor, was not involved in the AI model’s development but commented on its potential.

"AI models are emerging that are helping to manage responses to cancer treatments," he told Fox News Digital.

"These can allow for more treatment options and be more predictive of outcome."

AI models like this one are an example of "the essential future of personalized medicine," Siegel said, "where each patient is approached differently and their cancer is analyzed and treated with precision using genetic and protein analysis."

As long as physicians and scientists remain in charge — "not a computer or robot" — Siegel said that "there is no downside."

The AI model does carry some degree of limitations, the experts acknowledged.

"The models obviously do not return 100% accuracy," Wolber told Fox News Digital. "So there are some so-called false positives or false negatives."

NEW AI ‘CANCER CHATBOT’ PROVIDES PATIENTS AND FAMILIES WITH 24/7 SUPPORT: 'EMPATHETIC APPROACH'

The tool is not a "black box" that will provide a surefire answer, he noted. Rather, it's a tool that provides data points to the clinician and informs them as they make patient management decisions.

Osterman pointed out that the AI model uses a "relatively small dataset."

"We would love to be able to refine our predictions by learning on bigger data sets," he said.

The team is currently looking for partnerships that will enable them to test the AI model in new settings and achieve even higher accuracy in its predictions.

Another challenge, Osterman said, is the need to integrate these AI recommendations into the workflow.

"This is pretty new for us as a health care community, and I think we're all going to be wrestling with that question," he said.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Looking ahead, once the AI model has achieved the necessary regulatory approvals, GE HealthCare plans to make the technology available for widespread use by clinicians — perhaps even expanding to other care areas, such as neurology or cardiology.

There is also the potential to incorporate it into drug development.

"One of the things that drug makers struggle with is that some of the agents that may be really useful for some patients could be really toxic for others," Osterman said.

"If they were able to pick which patients could go into a trial and exclude patients with the highest risk of toxicity, that could mean the difference between that drug being made available or not."

He added, "If this means that we're able to help tailor that precision risk to patients, I'm in favor of that."

Ultimately, Osterman said, "it's a really exciting time to be in medicine … I think we're going to look back and regard this as the golden age of AI recommendations. I think they're probably here to stay."

1 year 6 months ago

Health, Cancer, cancer-research, artificial-intelligence, medical-tech, lifestyle, health-care, medications, medical-research

En California, la cobertura de salud ampliada a inmigrantes choca con las revisiones de Medicaid

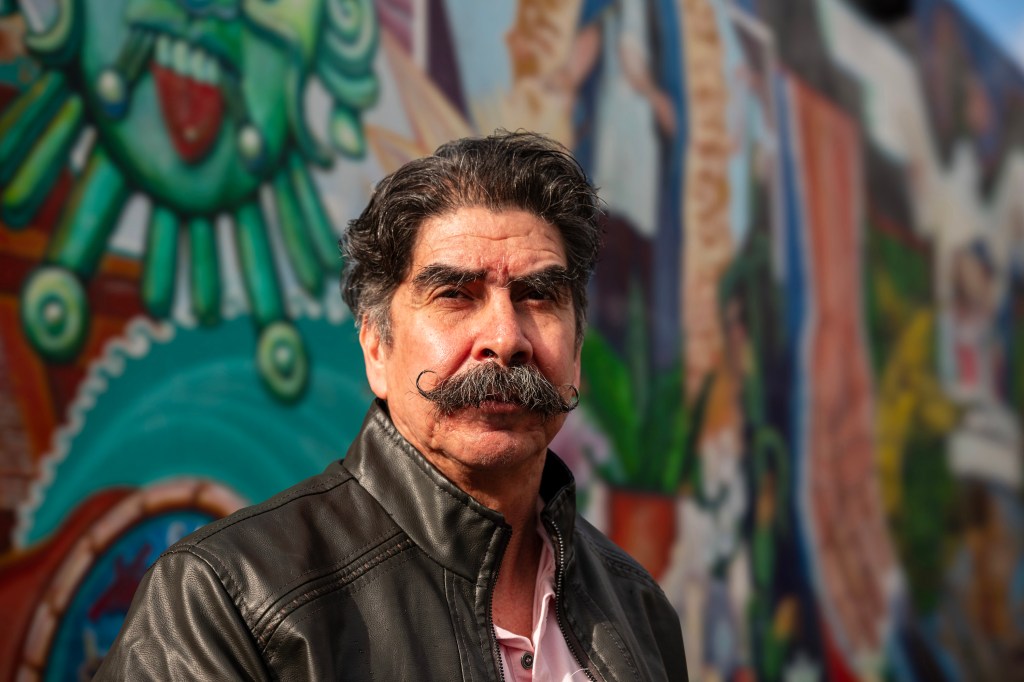

OAKLAND, California – El Medi-Cal llegó a Antonio Abundis cuando el conserje más lo necesitaba.

Poco después que Abundis pasara de tener cobertura limitada a una cobertura completa en 2022, bajo la expansión del Medi-Cal de California para adultos mayores sin papeles, fue diagnosticado con leucemia, un tipo de cáncer que afecta las células de la sangre.

OAKLAND, California – El Medi-Cal llegó a Antonio Abundis cuando el conserje más lo necesitaba.

Poco después que Abundis pasara de tener cobertura limitada a una cobertura completa en 2022, bajo la expansión del Medi-Cal de California para adultos mayores sin papeles, fue diagnosticado con leucemia, un tipo de cáncer que afecta las células de la sangre.

El padre de tres hijos, de voz suave, tomó la noticia con calma cuando su médico le dijo que sus análisis de sangre sugerían que su cáncer no estaba en una etapa avanzada. Sus siguientes pasos fueron hacerse más pruebas y tener un plan de tratamiento con un equipo de cáncer en Epic Care, en Emeryville.

Pero todo eso se fue por la borda cuando se presentó en julio pasado para hacerse un análisis de sangre en La Clínica de La Raza en Oakland, y le dijeron que ya no era beneficiario de Medi-Cal.

“Nunca mandaron una carta ni nada de que a mí me la había negado”, dijo Abundis, ahora de 63 años, sobre la pérdida de su cobertura.

Abundis es uno de los cientos de miles de latinos de California que han sido expulsados de Medi-Cal —el programa estatal de Medicaid para personas de bajos ingresos— a medida que los estados reanudaban las verificaciones de elegibilidad, que se habían suspendido en el punto más álgido de la pandemia de covid-19.

El proceso de redeterminación ha afectado de forma desproporcionada a los latinos, que constituyen la mayoría de los beneficiarios de Medi-Cal.

Según el Departamento de Servicios de Salud de California (DHCS), más de 613,000 de los 1,24 millones de residentes que fueron dados de baja se identifican como latinos. Algunos, incluido Abundis, habían obtenido la cobertura poco tiempo antes, cuando el estado comenzó a expandir Medi-Cal para ofrecer cobertura a inmigrantes indocumentados.

El choque entre las políticas estatales y las federales no sólo ha significado un duro golpe para los beneficiarios: también disparó la demanda de asistencia para realizar los trámites de inscripción.

Esto ocurre porque muchas personas son excluidas de Medi-Cal por cuestiones administrativas.

Los grupos de salud que trabajan con las comunidades latinas informan que están inundados de solicitudes de ayuda. Al mismo tiempo, una encuesta patrocinada por el estado sugiere que los hogares hispanos tienen más probabilidades que otros grupos étnicos o raciales de perder la cobertura porque tienen menos información sobre el proceso de renovación.

También pueden tener dificultades para defenderse por sí solos.

Algunos defensores de salud están presionando para que haya una pausa en este proceso. Advierten que las desafiliaciones no solo socavarán los esfuerzos del estado para reducir el número de personas sin seguro, sino que podrían exacerbar las disparidades en salud, especialmente para un grupo étnico que sufrió fuerte el peso de la pandemia.

Un estudio nacional encontró que los latinos en el país tuvieron tres veces más probabilidades de desarrollar covid y el doble de probabilidades de morir a causa de la enfermedad que la población en general, en parte porque tienden a vivir en hogares más hacinados o multigeneracionales y tienen trabajos en servicios, de cara al público.

“Estas dificultades nos colocan a todos como comunidad en un estatus más frágil, en el cual la red de seguridad es aún más significativa”, dijo Seciah Aquino, directora ejecutiva de la Latino Coalition for a Healthy California, una organización de defensa de salud.

La asambleísta Tasha Boerner (demócrata de Encinitas) ha presentado un proyecto de ley que desaceleraría las bajas permitiendo que las personas de 19 años o más mantengan automáticamente su cobertura durante 12 meses, y extendiendo las políticas flexibles de la era pandémica, como no requerir prueba de ingresos para renovar la cobertura en ciertos casos. Esto beneficiaría a los hispanos, que representan casi el 51% de la población de Medi-Cal en comparación con el 40% de la población total del estado.

La oficina del gobernador dijo que no comenta sobre proyectos legislativos que están aún en proceso.

Tony Cava, vocero del Departamento de Servicios de Atención Médica (DHCS), dijo en un correo electrónico que la agencia ha tomado medidas para aumentar el número de personas reinscritas automáticamente en Medi-Cal y no cree que sea necesaria una pausa. La tasa de desafiliación disminuyó un 10% de noviembre a diciembre, apuntó Cava.

Sin embargo, funcionarios estatales reconocen que se podría hacer más para ayudar a las personas a completar sus solicitudes. “Todavía no estamos llegando a ciertos sectores”, dijo Yingjia Huang, subdirectora adjunta de beneficios de atención médica y elegibilidad del DHCS.

California fue el primer estado en ampliar la elegibilidad de Medicaid a todos los inmigrantes que calificaran, sin importar su estatus migratorio, implementándolo gradualmente durante varios años: niños en 2016, adultos jóvenes de 19 a 26 años en 2020, personas de 50 años en adelante en 2022, y todos los adultos restantes este año.

Pero California, como otros estados, reanudó las verificaciones de elegibilidad en abril pasado, y se espera que el proceso continúe hasta mayo. El estado ahora está viendo que las tasas de desafiliación vuelven a los niveles previos a la pandemia, o el 19%-20% de la población de Medi-Cal cada año, según el DHCS.

Jane García, directora ejecutiva de La Clínica de La Raza, testificó ante el Comité de Salud de la Junta de Supervisores del condado de Alameda que las desafiliaciones siguen siendo un desafío, justo cuando su equipo intenta inscribir a residentes recién elegibles. “Es una carga enorme para nuestro personal”, les dijo a los supervisores en enero.

Aunque muchos beneficiarios ya no califican porque sus ingresos aumentaron, muchos más han sido eliminados de los registros por no responder a avisos o devolver documentos. En muchos casos, los paquetes de documentos para renovar la cobertura se enviaron a direcciones antiguas. Muchos se enteran de que perdieron la cobertura recién cuando van al médico.

“Sabían que algo estaba pasando”, dijo Janet Anwar, gerenta de elegibilidad en el Tiburcio Vásquez Health Center, en East Bay. “No sabían exactamente qué era, cómo los iba a afectar hasta que llegó el día y fueron desafiliados. Y estaban haciéndose un chequeo, o programando una cita, y luego… ‘Oye, perdiste tu cobertura'”.

Y la reinscripción es un desafío. Una encuesta patrocinada por el estado publicada el 12 de febrero por la California Health Care Foundation halló que el 30% de los hogares hispanos intentaron completar un formulario de renovación sin suerte, en comparación con el 19% de los hogares blancos no hispanos. Y el 43% de los hispanos informaron que les gustaría volver a comenzar con Medi-Cal, pero no sabían cómo, en comparación con el 32% de las personas en hogares blancos no hispanos.

La familia Abundis está entre las que no saben dónde obtener respuestas a sus preguntas. Aunque la esposa de Abundis envió la documentación de renovación de Medi-Cal para toda la familia en octubre, ella y dos hijos que aún viven con ellos pudieron mantener la cobertura; Abundis fue el único que la perdió.

No ha recibido una explicación de por qué lo sacaron de Medi-Cal ni ha sido notificado de cómo apelar o volver a solicitarlo.

Ahora se preocupa de que tal vez no califique por sí solo según sus ingresos anuales de aproximadamente $36,000, ya que el límite es de $20,121 para un individuo, pero de $41,400 para una familia de cuatro.

Es probable que un navegador pueda verificar si él y su familia califican como hogar para Medi-Cal. Covered California, el mercado de seguros de salud estatal, ofrece planes privados que pueden costar menos de $10 al mes en primas y permite una inscripción especial cuando las personas pierden Medi-Cal o la cobertura del empleador. Pero los inmigrantes que no viven legalmente en el estado no califican para los subsidios de Covered California. Abundis supone que no podrá pagar las primas ni los copagos, por lo que no presentó la solicitud.

Pero Abundis supone que no podrá pagar primas o copagos, así que no ha presentado una solicitud.

Abundis, quien visitó a un médico por primera vez en mayo de 2022 debido a una fatiga sin causa aparente, dolor constante en la espalda y las rodillas, falta de aliento y pérdida de peso inexplicable, teme no poder pagar la atención médica. La Clínica de La Raza, el centro de salud comunitario en donde le hicieron análisis de sangre, lo ayudó ese día a que no tuviera que pagar por adelantado, pero desde entonces dejó de buscar atención médica.

Más de un año después de su diagnóstico, todavía no sabe en qué etapa del cáncer se encuentra ni cuál debería ser su plan de tratamiento. Aunque la detección temprana del cáncer puede aumentar las posibilidades de supervivencia, algunos tipos de leucemia avanzan rápidamente. Sin más pruebas, Abundis no conoce su pronóstico.

Yo estoy mentalizado”, dijo Abundis sobre su cáncer. “Lo que pase, pase”.

Incluso aquellos que buscan ayuda se topan con desafíos. Marisol, una inmigrante mexicana sin papeles, de 53 años, que vive en Richmond, California, intentó restablecer la cobertura durante meses. Aunque el estado experimentó una caída del 26% en las bajas de diciembre a enero, la proporción de latinos a los que se les canceló la cobertura durante ese período permaneció casi igual, lo que sugiere que enfrentan más barreras para la renovación.

Marisol, quien pidió que se usara su nombre de pila por temor a la deportación, también calificó para la cobertura completa de Medi-Cal durante la expansión estatal a todos los inmigrantes de 50 años en adelante.

En diciembre, recibió un paquete informándole que los ingresos de su hogar excedían el umbral de Medi-Cal, algo que ella creyó que era un error. El esposo de Marisol está sin trabajo debido a una lesión en la espalda, dijo, y sus dos hijos mantienen a su familia principalmente con trabajos de medio tiempo en Ross Dress for Less.

Ese mes, Marisol visitó una sucursal de Richmond del Departamento de Empleo y Servicios Humanos del condado de Contra Costa, con la esperanza de hablar con un navegador. En cambio, le dijeron que dejara su documentación y que llamara a un número de teléfono para verificar el estatus de su solicitud.

Desde entonces, llamó muchas veces y pasó horas en espera, pero no ha podido hablar con nadie. Los funcionarios del condado reconocieron tiempos de espera más prolongados debido al aumento de llamadas, y dijeron que el tiempo promedio es de 30 minutos.

“Entendemos la frustración de los miembros de la comunidad cuando a veces tienen dificultades para comunicarse”, escribió la vocera Tish Gallegos en un correo electrónico. Gallegos señaló que el centro de llamadas aumenta la dotación de personal durante las horas pico.

Después que El Tímpano contactara al condado para hacer comentarios, Marisol dijo que un trabajador de elegibilidad la contactó, y le explicó que su familia fue dada de baja porque sus hijos habían presentado impuestos por separado, por lo que el sistema de Medi-Cal determinó su elegibilidad individualmente en lugar de como familia.

El condado reintegró a Marisol y a su familia el 15 de marzo. Marisol dijo que recuperar Medi-Cal fue un final alegre pero agridulce para una lucha de meses, especialmente sabiendo que otras personas son desafiliadas por cuestiones de procedimiento. “Tristemente, tiene que haber presión para que arreglen algo”, dijo.

Jasmine Aguilera de El Tímpano está participando de la Journalism & Women Symposium’s Health Journalism Fellowship, apoyada por The Commonwealth Fund. Vanessa Flores, Katherine Nagasawa e Hiram Alejandro Durán de El Tímpano colaboraron con este artículo.

[Corrección: este artículo se actualizó a la 1:30 pm (ET), el 26 de marzo de 2024, para corregir los detalles sobre la elegibilidad para recibir asistencia financiera para pagar las primas de los seguros. Los inmigrantes que no viven legalmente en California no califican para los subsidios de Covered California].

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 7 months ago

Health Care Costs, Insurance, Medi-Cal, Medicaid, Noticias En Español, Race and Health, States, Uninsured, Cancer, Latinos, Out-Of-Pocket Costs

How red and processed meats contribute to cancer

The Grenada Food and Nutrition Council advises choosing lean cuts of fresh meat and poultry, limiting red meats, eating more fish and adding plenty of plant-based proteins several times a week

View the full post How red and processed meats contribute to cancer on NOW Grenada.

1 year 8 months ago

Health, PRESS RELEASE, Cancer, cancer research uk, carcinogens, gfnc, grenada food and nutrition council, haem, who, world health organisation

Patients See First Savings From Biden’s Drug Price Push, as Pharma Lines Up Its Lawyers

Last year alone, David Mitchell paid $16,525 for 12 little bottles of Pomalyst, one of the pricey medications that treat his multiple myeloma, a blood cancer he was diagnosed with in 2010.

The drugs have kept his cancer at bay. But their rapidly increasing costs so infuriated Mitchell that he was inspired to create an advocacy movement.

Last year alone, David Mitchell paid $16,525 for 12 little bottles of Pomalyst, one of the pricey medications that treat his multiple myeloma, a blood cancer he was diagnosed with in 2010.

The drugs have kept his cancer at bay. But their rapidly increasing costs so infuriated Mitchell that he was inspired to create an advocacy movement.

Patients for Affordable Drugs, which he founded in 2016, was instrumental in getting drug price reforms into the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Those changes are kicking in now, and Mitchell, 73, is an early beneficiary.

In January, he plunked down $3,308 for a Pomalyst refill “and that’s it,” he said. Under the law, he has no further responsibility for his drug costs this year — a savings of more than $13,000.

The law caps out-of-pocket spending on brand-name drugs for Medicare beneficiaries at about $3,500 in 2024. The patient cap for all drugs drops to $2,000 next year.

“From a selfish perspective, I feel great about it,” he said. But the payment cap will be “truly life-changing” for hundreds of thousands of other Medicare patients, Mitchell said.

President Joe Biden’s battle against high drug prices is mostly embodied in the IRA, as the law is known — a grab bag of measures intended to give Medicare patients immediate relief and, in the long term, to impose government controls on what pharmaceutical companies charge for their products. The law represents the most significant overhaul for the U.S. drug marketplace in decades.

With Election Day on the horizon, the president is trying to make sure voters know who was responsible. This month, the White House began a campaign to get the word out to seniors.

“The days where Americans pay two to three times what they pay for prescription drugs in other countries are ending,” Biden said in a Feb. 1 statement.

KFF polling indicates Biden has work to do. Just a quarter of adults were aware that the IRA includes provisions on drug prices in July, nearly a year after the president signed it. He isn’t helped by the name of the law, the “Inflation Reduction Act,” which says nothing about health care or drug costs.

Biden’s own estimate of drug price inflation is quite conservative: U.S. patients sometimes pay more than 10 times as much for their drugs compared with people in other countries. The popular weight loss drug Wegovy lists for $936 a month in the U.S., for example — and $83 in France.

Additional sections of the law provide free vaccines and $35-a-month insulin and federal subsidies to patients earning up to 150% of the federal poverty level, and require drugmakers to pay the government rebates for medicines whose prices rise faster than inflation. But the most controversial provision enables Medicare to negotiate prices for certain expensive drugs that have been on the market for at least nine years. It’s key to Biden’s attempt to weaken the drug industry’s grip.

Responding to Pressure

The impact of Medicare’s bargaining over drug prices for privately insured Americans remains unclear. States have taken additional steps, such as cutting copays for insulin for the privately insured.

However, insurers are increasing premiums in response to their higher costs under the IRA. Monthly premiums on traditional Medicare drug plans jumped to $48 from $40 this year, on average.

On Feb. 1, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sent pharmaceutical makers opening bids for the first 10 expensive drugs it selected for negotiation. The companies are responding to the bids — while filing nine lawsuits that aim to kill the negotiations altogether, arguing that limiting their profits will strangle the pipeline of lifesaving drugs. A federal court in Texas dismissed one of the suits on Feb. 12, without taking up the substantive legal issue over constitutionality.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office predicted the IRA’s drug pricing elements would save the federal government $237 billion over 10 years while reducing the number of drugs coming to market in that period by about two.

If the government prevails in the courts, new prices for those 10 drugs will be announced by September and take effect in 2026. The government will negotiate an additional 15 drugs for 2027, another 15 for 2028, and 20 more each year thereafter. CMS has been mum about the size of its offers, but AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot on Feb. 8 called the opening bid for his company’s drug Farxiga (which earned $2.8 billion in U.S. sales in fiscal year 2023) “relatively encouraging.”

Related Biden administration efforts, as well as legislation with bipartisan support, could complement the Inflation Reduction Act’s swing at drug prices.

The House and Senate have passed bills that require greater transparency and less self-serving behavior by pharmacy benefit managers, the secretive intermediaries that decide which drugs go on patients’ formularies, the lists detailing which prescriptions are available to health plan enrollees. The Federal Trade Commission is investigating anti-competitive action by leading PBMs, as well as drug company patenting tricks that slow the entry of cheaper drugs to the market.

‘Sending a Message’

Months after drug companies began suing to stop price negotiations, the Biden administration released a framework describing when it could “march in” and essentially seize drugs created through research funded by the National Institutes of Health if they are unreasonably priced.

The timing of the march-in announcement “suggests that it’s about sending a message” to the drug industry, said Robin Feldman, who leads the Center for Innovation at the University of California Law-San Francisco. And so, in a way, does the Inflation Reduction Act itself, she said.

“I have always thought that the IRA would reverberate well beyond the unlucky 10 and others that get pulled into the net later,” Feldman said. “Companies are likely to try to moderate their behavior to stay out of negotiations. I think of all the things going on as attempts to corral the market into more reasonable pathways.”

The IRA issues did not appear to be top of mind to most executives and investors as they gathered to make deals at the annual J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco last month.

“I think the industry is navigating its way beyond this,” said Matthew Price, chief operating officer of Promontory Therapeutics, a cancer drug startup, in an interview there. The drugs up for negotiation “look to be assets that were already nearing the end of their patent life. So maybe the impact on revenues is less than feared. There’s alarm around this, but it was probably inevitable that a negotiation mechanism of some kind would have to come in.”

Investors generally appear sanguine about the impact of the law. A recent S&P Global report suggests “healthy revenue growth through 2027” for the pharmaceutical industry.

Back in Washington, many of the changes await action by the courts and Congress and could be shelved depending on the results of the fall election.

The restructuring of Medicare Part D, which covers most retail prescription drugs, is already lowering costs for many Medicare patients who spent more than $3,500 a year on their Part D drugs. In 2020 that was about 1.3 million patients, 200,000 of whom spent $5,000 or more out-of-pocket, according to KFF research.

“That’s real savings,” said Tricia Neuman, executive director of KFF’s Medicare policy program, “and it’s targeted to people who are really sick.”

Although the drug industry is spending millions to fight the IRA, the Part D portion of the bill could end up boosting their sales. While it forces the industry to further discount the highest-grossing drugs, the bill makes it easier for Medicare patients to pick up their medicines because they’ll be able to afford them, said Stacie Dusetzina, a Vanderbilt University School of Medicine researcher. She was the lead author of a 2022 study showing that cancer patients who didn’t get income subsidies were about half as likely to fill prescriptions.

States and foundations that help patients pay for their drugs will save money, enabling them to procure more drugs for more patients, said Gina Upchurch, the executive director of Senior PharmAssist, a Durham, North Carolina-based drug assistance program, and a member of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. “This is good news for the drug companies,” she said.

Relief for Patients

Lynn Scarfuto, 73, a retired nurse who lives on a fixed income in upstate New York, spent $1,157 for drugs last year, while most of her share of the $205,000 annual cost for the leukemia drug Imbruvica was paid by a charity, the Patient Access Network Foundation. This year, through the IRA, she’ll pay nothing because the foundation’s first monthly Imbruvica payment covered her entire responsibility. Imbruvica, marketed jointly by AbbVie and Janssen, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, is one of the 10 drugs subject to Medicare negotiations.

“For Medicare patients, the Inflation Reduction Act is a great, wonderful thing,” Scarfuto said. “I hope the negotiation continues as they have promised, adding more drugs every year.”

Mitchell, a PR specialist who had worked with such clients as the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and pharmaceutical giant J&J, went to an emergency room with severe back pain in November 2010 and discovered he had a cancer that had broken a vertebra and five ribs and left holes in his pelvis, skull, and forearm bones. He responded well to surgery and treatment but was shocked at the price of his drugs.

His Patients for Affordable Drugs group has become a powerful voice in Washington, engaging tens of thousands of patients, including Scarfuto, to tell their stories and lobby legislatures. The work is supported in part by millions in grants from Arnold Ventures, a philanthropy that has supported health care policies like lower drug prices, access to contraception, and solutions to the opioid epidemic.

“What got the IRA over the finish line in part was angry people who said we want something done with this,” Mitchell said. “Our patients gave voice to that.”

Arnold Ventures has provided funding for KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 8 months ago

Courts, Health Care Costs, Health Industry, Insurance, Medicare, Pharmaceuticals, Biden Administration, Cancer, Drug Costs, New York, Treating Cancer

Cancer causes: These 10 hidden carcinogens can raise the risk, according to an oncology expert

Many of cancer’s effects are visible — but the causes aren’t always so obvious.

There are hundreds of different types of cancer, and far more causes.

Many of cancer’s effects are visible — but the causes aren’t always so obvious.

There are hundreds of different types of cancer, and far more causes.

"Cancer-causing agents, known as carcinogens, can be of various types and forms, working toward triggering mutations in the human body that lead to the development of cancer," said Dr. John Oertle, chief medical director at Envita Medical Centers in Scottsdale, Arizona.

THESE 8 HEALTH SCREENINGS SHOULD BE ON YOUR CALENDAR FOR 2024, ACCORDING TO DOCTORS

While some causes, such as tobacco use and UV radiation, are widely known for their harmful effects, there are many other hidden carcinogens in the environment that are equally harmful, the doctor told Fox News Digital.

"These hidden carcinogens are ubiquitous but often avoidable if people are aware of their inherent dangers," Oertle said.

"Environmental carcinogens often involve synthetic derivatives of industrial byproducts in addition to solvents, heavy metals, pesticides, radioisotopes and even carcinogenic microbes."

The doctor shared a list of some of these hidden carcinogens, their sources and the types of cancer they cause.

Dr. Marc Siegel, clinical professor of medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center and a Fox News medical contributor, described Oertle's list as "important."

"Even though we talk about potential carcinogens all the time, the ones mentioned in this list are the major players," he told Fox News Digital.

"Though we are very familiar with the carcinogenic risks of tobacco, and UV light to the skin, others, like radon, are too frequently underestimated."

This carcinogen comes from cigarettes, leading to about 20% of all cancers and approximately 30% of cancer-related deaths in the country, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS).

FOODS TO EAT, AND NOT EAT, TO PREVENT CANCER, ACCORDING TO A DOCTOR AND NUTRITIONIST

Tobacco can cause cancer of the mouth, nose, throat, larynx, trachea, esophagus, lungs, stomach, pancreas, liver, kidneys, ureters, bladder, colon, rectum and cervix, as well as leukemia, noted Oertle.

Organochlorines are pesticides that have been used in agriculture around the world since they were introduced in the 1940s, despite having high toxicity.

While they’ve been largely banned in the U.S. due to health hazards, they are still used in other countries, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Organochlorines can potentially lead to breast, colorectal, pancreatic, prostate, lung, oral/nasopharyngeal, thyroid, adrenal and gallbladder cancer, as well as lymphoma, according to Oertle.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are chemicals found in coal, crude oil and gasoline, according to the CDC.

They are emitted into the environment with the burning of coal, oil, gas, wood, garbage and tobacco.

ANNUAL BREAST CANCER SCREENINGS LINKED TO LOWER RISK OF DEATH, STUDY FINDS

PAHs can come from cigarette smoke, vehicular exhaust, roofing tar, occupational settings and pharmaceuticals, Oertle said.

Breast, skin, lung, bladder and gastrointestinal cancers can stem from exposure to these chemicals.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are chemicals emitted through the creation of paints, pharmaceuticals and refrigerants, among other products, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

They are also found in industrial solvents, petroleum fuels and dry cleaning agents.

VOCs are commonly found in the air, groundwater, cigarette smoke, automobile emissions and gasoline, Oertle warned.

The compounds can cause lung, nasopharyngeal, lymphohematopoietic and sinonasal cancers, as well as leukemia.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the World Health Organization (WHO) both classify ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun and tanning beds as a human carcinogen.

UV rays can cause a variety of skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.

TO REDUCE CANCER RISK, SKIP THE ALCOHOL, REPORT SUGGESTS: ‘NO SAFE AMOUNT’

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the U.S., affecting one in five Americans in their lifetimes and resulting in 9,500 diagnoses each day.

A radioactive gas, radon is a byproduct of uranium, thorium or radium breaking down in rocks, soil and groundwater, according to the EPA.

When radon seeps into buildings and homes, people can breathe it in — increasing their risk of leukemia, lymphoma, skin cancer, thyroid cancer, various sarcomas, lung cancer and breast cancer, Oertle said.

A mineral fiber in rock and soil, asbestos has historically been used in construction materials.

Although some uses have been banned, it can still be found in insulation, roofing and siding shingles, vinyl floor tiles, heat-resistant fabrics and some other materials, per the EPA.

VACCINE FOR DEADLY SKIN CANCER SHOWS ‘GROUNDBREAKING’ RESULTS IN CLINICAL TRIAL

Oertle warned that asbestos exposure can increase the risk of lung, mesothelioma, gastrointestinal, colorectal, throat, kidney, esophagus and gallbladder cancers.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines cadmium as "a soft, malleable, bluish white metal found in zinc ores, and to a much lesser extent, in the cadmium mineral greenockite."

Cadmium can be found in paints, batteries and plastics, Oertle said.

The metal can be a factor in lung, prostate, pancreatic and renal cancers.

There are two types of this trace mineral, as noted on WebMD’s website.

One is trivalent chromium, which is not harmful to humans. The other type, hexavalent chromium, is considered toxic.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Sources of the harmful chromium include chrome plating, welding, leather tanning and ferrochrome metals.

Inhalation of chromium, a known human carcinogen, has been shown to cause lung cancer in steel workers, per the CDC.

A heavy metal that is a known carcinogen, nickel is found in electroplating, circuitry, electroforming and batteries, noted Oertle.

Nickel has been linked to an increased risk of lung and nasal cancers, per the National Cancer Institute.

Overall, more than 1.9 million new cancer cases were diagnosed in the U.S. in 2023, and around 609,820 cancer-related deaths were reported, according to the ACS.

Dr. Brett Osborn, a Florida neurologist and owner of Senolytix, a longevity-based health consultancy, pointed out that in addition to being aware of the various carcinogens and limiting exposure to them, it's also important to take measures to quell inflammation.

"Nearly all age-related diseases, of which cancer is one, are underpinned by low levels of inflammation," Osborn told Fox News Digital.

To reduce inflammation, the doctor recommends eating a low glycemic index diet rich in olive oil and omega-3 fatty acids from fish or flax, strength training regularly, getting adequate sleep and using a probiotic supplement.

"Show your body the right signals, and it will respond in kind – you’ll have your health," Osborn said. "Expose it to the wrong signals and you'll turn on the ‘oncogenes’ that cause cancer."

The doctor added, "Cancer, aside from those associated with a specific gene mutation (typically pediatric cancer), is an ‘environmental’ disease, period."

1 year 9 months ago

Health, Cancer, cancer-research, lifestyle, medical-research, breast-cancer, Environment

The biotech news you missed from the weekend

Want to stay on top of the science and politics driving biotech today? Sign up to get our biotech newsletter in your inbox.

Hello from ASH! Writing this Readout from a press room at the annual hematology confab here in San Diego. Today’s edition is chockfull of Vertex content, plus some extras from ASH and elsewhere.

Want to stay on top of the science and politics driving biotech today? Sign up to get our biotech newsletter in your inbox.

Hello from ASH! Writing this Readout from a press room at the annual hematology confab here in San Diego. Today’s edition is chockfull of Vertex content, plus some extras from ASH and elsewhere.

1 year 10 months ago

Biotech, Business, Health, Pharma, Politics, The Readout, biotechnology, Cancer, drug development, drug pricing, FDA, finance, genetics, Pharmaceuticals, Research

AbbVie’s big deal, CAR-T’s risks, & getting a biotech job

Are ADCs having a moment? Is CAR-T safe? And who’s to blame for failed trials?

We cover all that and more this week on “The Readout LOUD,” STAT’s biotech podcast. We discuss why AbbVie is spending $10 billion on a cancer-focused company that spent four decades on the path to its first FDA approval, a deal with implications for biotech in 2023 and for a burgeoning area in oncology. We’ll also talk about the latest news in the life sciences, including safety concerns for CAR-T cancer treatment, the slumping industry job market, and some curious explanations for clinical failures.

1 year 11 months ago

The Readout LOUD, AbbVie, biotechnology, Cancer, life sciences

STAT+: AbbVie buys Immunogen, maker of targeted cancer drugs, for $10 billion

AbbVie will pay $10 billion for the biotech firm Immunogen, the company said Thursday, acquiring an approved treatment for ovarian cancer and buying into a burgeoning area of oncology.

Under the agreement, AbbVie will pay $31.26 per share in cash for Immunogen, a nearly 100% premium to the company’s recent trading price. Central to the deal, expected to close in the middle of next year, is Elahere, an Immunogen product that won Food and Drug Administration approval for advanced ovarian cancer in 2022.

Elahere is among a surging class of cancer medicines called antibody-drug conjugates, or ADCs, which are designed to deliver a targeted dose of chemotherapy directly to tumor cells while sparing healthy tissues. AbbVie’s acquisition is the latest multibillion-dollar deal in the space, following Merck’s $22 billion agreement with ADC specialist Daiichi Sankyo and Pfizer’s $43 billion buyout of Seagen earlier this year.

1 year 11 months ago

Biotech, biotechnology, Cancer, STAT+