Vance-Walz Debate Highlighted Clear Health Policy Differences

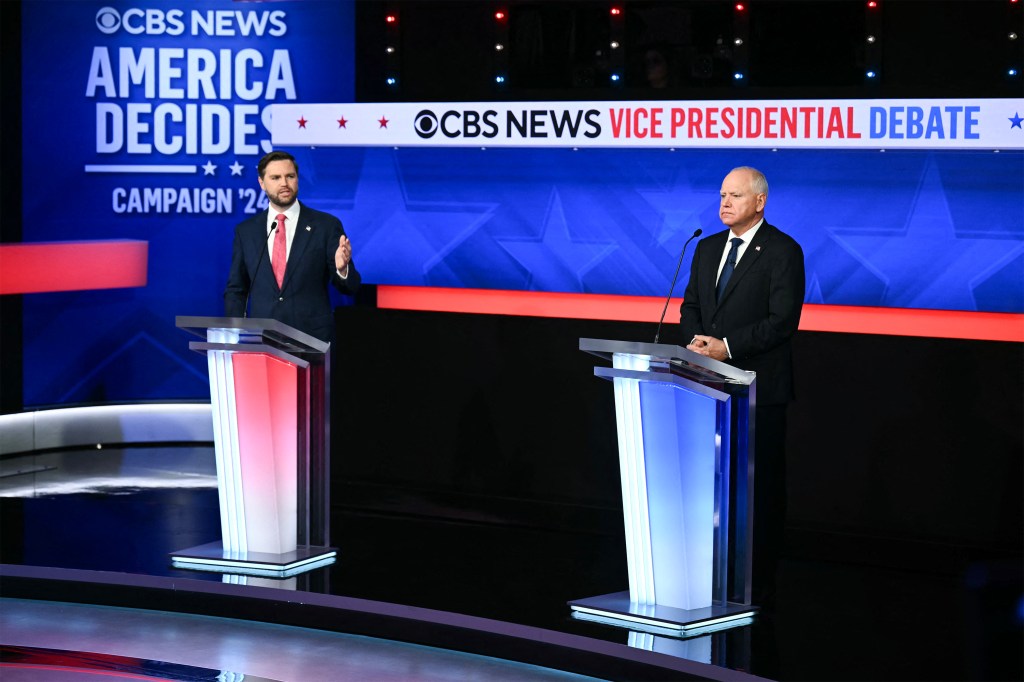

Ohio Republican Sen. JD Vance and Minnesota Democratic Gov. Tim Walz met in an Oct. 1 vice presidential debate hosted by CBS News that was cordial and heavy on policy discussion — a striking change from the Sept. 10 debate between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump.

Ohio Republican Sen. JD Vance and Minnesota Democratic Gov. Tim Walz met in an Oct. 1 vice presidential debate hosted by CBS News that was cordial and heavy on policy discussion — a striking change from the Sept. 10 debate between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump.

Vance and Walz acknowledged occasional agreement on policy points and respectfully addressed each other throughout the debate. But they were more pointed in their attacks on their rival’s running mate for challenges facing the country, including immigration and inflation.

The moderators, “CBS Evening News” anchor Norah O’Donnell and “Face the Nation” host Margaret Brennan, had said they planned to encourage candidates to fact-check each other, but sometimes clarified statements from the candidates.

After Vance made assertions about Springfield, Ohio, being overrun by “illegal immigrants,” Brennan pointed out that a large number of Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, are in the country legally. Vance objected and, eventually, CBS exercised the debate ground rule that allowed the network to cut off the candidates’ microphones.

Most points were not fact-checked in real time by the moderators. Vance resurfaced a recent health care theme — that as president, Donald Trump sought to save the Affordable Care Act — and acknowledged that he would support a national abortion ban.

Walz described how health care looked before the ACA compared with today. Vance offered details about Trump’s health care “concepts of a plan” — a reference to comments Trump made during the presidential debate that drew jeers and criticism for the former president, who for years said he had a plan to replace the ACA that never surfaced. Vance pointed to regulatory changes advanced during the Trump administration, used weedy phrases like “reinsurance regulations,” and floated the idea of allowing states “to experiment a little bit on how to cover both the chronically ill but the non-chronically ill.”

Walz responded with a quick quip: “Here’s where being an old guy gives you some history. I was there at the creation of the ACA.” He said that before then insurers had more power to kick people off their plans. Then he detailed Trump’s efforts to undo the ACA as well as why the law’s preexisting condition protections were important.

“What Sen. Vance just explained might be worse than a concept, because what he explained is pre-Obamacare,” Walz said.

The candidates sparred on numerous topics. Our PolitiFact partners fact-checked the debate here and on their live blog.

The health-related excerpts follow.

The Affordable Care Act:

Vance: “Donald Trump could have destroyed the [Affordable Care Act]. Instead, he worked in a bipartisan way to ensure that Americans had access to affordable care.”

As president, Trump worked to undermine and repeal the Affordable Care Act. He cut millions of dollars in federal funding for ACA outreach and navigators who help people sign up for health coverage. He enabled the sale of short-term health plans that don’t comply with the ACA consumer protections and allowed them to be sold for longer durations, which siphoned people away from the health law’s marketplaces.

Trump’s administration also backed state Medicaid waivers that imposed first-ever work requirements, reducing enrollment. He also ended insurance company subsidies that helped offset costs for low-income enrollees. He backed an unsuccessful repeal of the landmark 2010 health law and he backed the demise of a penalty imposed for failing to purchase health insurance.

Affordable Care Act enrollment declined by more than 2 million people during Trump’s presidency, and the number of uninsured Americans rose by 2.3 million, including 726,000 children, from 2016 to 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau reported; that includes three years of Trump’s presidency. The number of insured Americans rose again during the Biden administration.

Abortion and Reproductive Health:

Vance: “As I read the Minnesota law that [Walz] signed into law … it says that a doctor who presides over an abortion where the baby survives, the doctor is under no obligation to provide lifesaving care to a baby who survives a botched late-term abortion.”

Experts said cases in which a baby is born following an attempted abortion are rare. Less than 1% of abortions nationwide occur in the third trimester. And infanticide, the crime of killing a child within a year of its birth, is illegal in every state.

In May 2023, Walz, as Minnesota governor, signed legislation updating a state law for “infants who are born alive.” It said babies are “fully recognized” as human people and therefore protected under state law. The change did not alter regulations that already required doctors to provide patients with appropriate care.

Previously, state law said, “All reasonable measures consistent with good medical practice, including the compilation of appropriate medical records, shall be taken by the responsible medical personnel to preserve the life and health of the born alive infant.” The law was updated to instead say medical personnel must “care for the infant who is born alive.”

When there are fetal anomalies that make it likely the fetus will die before or soon after birth, some parents decide to terminate the pregnancy by inducing childbirth so that they can hold their dying baby, Democratic Minnesota state Sen. Erin Maye Quade told PolitiFact in September.

This update to the law means infants who are “born alive” receive appropriate medical care dependent on the pregnancy’s circumstances, Maye Quade said.

Vance supported a national abortion ban before becoming Trump’s running mate.

CBS News moderator Margaret Brennan told Vance, “You have supported a federal ban on abortion after 15 weeks. In fact, you said if someone can’t support legislation like that, quote, ‘you are making the United States the most barbaric pro-abortion regime anywhere in the entire world.’ My question is, why have you changed your position?”

Vance said that he “never supported a national ban” and, instead, previously supported setting “some minimum national standard.”

But in a January 2022 podcast interview, Vance said, “I certainly would like abortion to be illegal nationally.” In November, he told reporters that “we can’t give in to the idea that the federal Congress has no role in this matter.”

Since joining the Trump ticket, Vance has aligned his abortion rhetoric to match Trump’s and has said that abortion legislation should be left up to the states.

— Samantha Putterman of PolitiFact, on the live blog

A woman’s 2022 death in Georgia following the state passing its six-week abortion ban was deemed “preventable.”

Walz talked about the death of 28-year-old Amber Thurman, a Georgia woman who died after her care was delayed because of the state’s six-week abortion law. A judge called the law unconstitutional this week.

A Sept. 16 ProPublica report found that Thurman had taken abortion pills and encountered a rare complication. She sought care at Piedmont Henry Hospital in Atlanta to clear excess fetal tissue from her uterus, called a dilation and curettage, or D&C. The procedure is commonly used in abortions, and any doctor who violated Georgia’s law could be prosecuted and face up to a decade in prison.

Doctors waited 20 hours to finally operate, when Thurman’s organs were already failing, ProPublica reported. A panel of health experts tasked with examining pregnancy-related deaths to improve maternal health deemed Thurman’s death “preventable,” according to the report, and said the hospital’s delay in performing the procedure had a “large” impact.

— Samantha Putterman of PolitiFact, on the live blog

What Project 2025 Says About Some Forms of Contraception, Fertility Treatments

Walz said that Project 2025 would “make it more difficult, if not impossible, to get contraception and limit access, if not eliminate access, to fertility treatments.”

Mostly False. The Project 2025 document doesn’t call for restricting standard contraceptive methods, such as birth control pills, but it defines emergency contraceptives as “abortifacients” and says they should be eliminated from the Affordable Care Act’s covered preventive services. Emergency contraception, such as Plan B and ella, are not considered abortifacients, according to medical experts.

PolitiFact did not find any mention of in vitro fertilization throughout the document, or specific recommendations to curtail the practice in the U.S., but it contains language that supports legal rights for fetuses and embryos. Experts say this language can threaten family planning methods, including IVF and some forms of contraception.

— Samantha Putterman of PolitiFact, on the live blog

Walz: “Their Project 2025 is gonna have a registry of pregnancies.”

Project 2025 recommends that states submit more detailed abortion reporting to the federal government. It calls for more information about how and when abortions took place, as well as other statistics for miscarriages and stillbirths.

The manual does not mention, nor call for, a new federal agency tasked with registering pregnant women.

Fentanyl and Opioids:

Vance: “Kamala Harris let in fentanyl into our communities at record levels.”

Mostly False.

Illicit fentanyl seizures have been rising for years and reached record highs under Biden’s administration. In fiscal year 2015, for example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized 70 pounds of fentanyl. As of August 2024, agents have seized more than 19,000 pounds of fentanyl in fiscal year 2024, which ended in September.

But these are fentanyl seizures — not the amount of the narcotic being “let” into the United States.

Vance made this claim while criticizing Harris’ immigration policies. But fentanyl enters the U.S. through the southern border mainly at official ports of entry. It’s mostly smuggled in by U.S. citizens, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission. Most illicit fentanyl in the U.S. comes from Mexico made with chemicals from Chinese labs.

Drug policy experts have said that the illicit fentanyl crisis began years before Biden’s administration and that Biden’s border policies are not to blame for overdose deaths.

Experts have also said Congress plays a role in reducing illicit fentanyl. Congressional funding for more vehicle scanners would help law enforcement seize more of the fentanyl that comes into the U.S. Harris has called for increased enforcement against illicit fentanyl use.

Walz: “And the good news on this is, is the last 12 months saw the largest decrease in opioid deaths in our nation’s history.”

Mostly True.

Overdose deaths involving opioids decreased from an estimated 84,181 in 2022 to 81,083 in 2023, based on the most recent provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This decrease, which took place in the second half of 2023, followed a 67% increase in opioid-related deaths between 2017 and 2023.

The U.S. had an estimated 107,543 drug overdose deaths in 2023 — a 3% decrease from the 111,029 deaths estimated in 2022. This is the first annual decrease in overall drug overdose deaths since 2018. Nevertheless, the opioid death toll remains much higher than just a few years ago, according to KFF.

More Health-Related Comments:

Vance Said ‘Hospitals Are Overwhelmed.’ Local Officials Disagree.

We asked health officials ahead of the debate what they thought about Vance’s claims about Springfield’s emergency rooms being overwhelmed.

“This claim is not accurate,” said Chris Cook, health commissioner for Springfield’s Clark County.

Comparison data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services tracks how many patients are “left without being seen” as part of its effort to characterize whether ERs are able to handle their patient loads. High percentages usually signal that the facility doesn’t have the staff or resources to provide timely and effective emergency care.

Cook said that the full-service hospital, Mercy Health Springfield Regional Medical Center, reports its emergency department is at or better than industry standard when it comes to this metric.

In July 2024, 3% of Mercy Health’s patients were counted in the “left-without-being-seen” category — the same level as both the state and national average for high-volume hospitals. In July 2019, Mercy Health tallied 2% of patients who “left without being seen.” That year, the state and national averages were 1% and 2%, respectively. Another CMS 2024 data point shows Mercy Health patients spent less time in the ER per visit on average — 152 minutes — compared with state and national figures: 183 minutes and 211 minutes, respectively. Even so, Springfield Regional Medical Center’s Jennifer Robinson noted that Mercy Health has seen high utilization of women’s health, emergency, and primary care services.

— Stephanie Armour, Holly Hacker, and Stephanie Stapleton of KFF Health News, on the live blog

Minnesota’s Paid Leave Takes Effect in 2026

Walz signed paid family leave into law in 2023 and it will take effect in 2026.

The law will provide employees up to 12 weeks of paid medical leave and up to 12 weeks of paid family leave, which includes bonding with a child, caring for a family member, supporting survivors of domestic violence or sexual assault, and supporting active-duty deployments. A maximum 20 weeks are available in a benefit year if someone takes both medical and family leave.

Minnesota used a projected budget surplus to jump-start the program; funding will then shift to a payroll tax split between employers and workers.

— Amy Sherman of PolitiFact, on the live blog

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 3 weeks ago

Elections, Health Care Costs, Insurance, States, Abortion, Children's Health, Contraception, Guns, Hospitals, Immigrants, KFF Health News & PolitiFact HealthCheck, Minnesota, Obamacare Plans, Ohio, Opioids, Substance Misuse, Women's Health

Why Many Nonprofit (Wink, Wink) Hospitals Are Rolling in Money

One owns a for-profit insurer, a venture capital company, and for-profit hospitals in Italy and Kazakhstan; it has just acquired its fourth

One owns a for-profit insurer, a venture capital company, and for-profit hospitals in Italy and Kazakhstan; it has just acquired its fourth for-profit hospital in Ireland. Another owns one of the largest for-profit hospitals in London, is partnering to build a massive training facility for a professional basketball team, and has launched and financed 80 for-profit start-ups. Another partners with a wellness spa where rooms cost $4,000 a night and co-invests with “leading private equity firms.”

Do these sound like charities?

These diversified businesses are, in fact, some of the country’s largest nonprofit hospital systems. And they have somehow managed to keep myriad for-profit enterprises under their nonprofit umbrella — a status that means they pay little or no taxes, float bonds at preferred rates, and gain numerous other financial advantages.

Through legal maneuvering, regulatory neglect, and a large dollop of lobbying, they have remained tax-exempt charities, classified as 501(c)(3)s.

“Hospitals are some of the biggest businesses in the U.S. — nonprofit in name only,” said Martin Gaynor, an economics and public policy professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “They realized they could own for-profit businesses and keep their not-for-profit status. So the parking lot is for-profit; the laundry service is for-profit; they open up for-profit entities in other countries that are expressly for making money. Great work if you can get it.”

Many universities’ most robust income streams come from their technically nonprofit hospitals. At Stanford University, 62% of operating revenue in fiscal 2023 was from health services; at the University of Chicago, patient services brought in 49% of operating revenue in fiscal 2022.

To be sure, many hospitals’ major source of income is still likely to be pricey patient care. Because they are nonprofit and therefore, by definition, can’t show that thing called “profit,” excess earnings are called “operating surpluses.” Meanwhile, some nonprofit hospitals, particularly in rural areas and inner cities, struggle to stay afloat because they depend heavily on lower payments from Medicaid and Medicare and have no alternative income streams.

But investments are making “a bigger and bigger difference” in the bottom line of many big systems, said Ge Bai, a professor of health care accounting at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. Investment income helped Cleveland Clinic overcome the deficit incurred during the pandemic.

When many U.S. hospitals were founded over the past two centuries, mostly by religious groups, they were accorded nonprofit status for doling out free care during an era in which fewer people had insurance and bills were modest. The institutions operated on razor-thin margins. But as more Americans gained insurance and medical treatments became more effective — and more expensive — there was money to be made.

Not-for-profit hospitals merged with one another, pursuing economies of scale, like joint purchasing of linens and surgical supplies. Then, in this century, they also began acquiring parts of the health care systems that had long been for-profit, such as doctors’ groups, as well as imaging and surgery centers. That raised some legal eyebrows — how could a nonprofit simply acquire a for-profit? — but regulators and the IRS let it ride.

And in recent years, partnerships with, and ownership of, profit-making ventures have strayed further and further afield from the purported charitable health care mission in their community.

“When I first encountered it, I was dumbfounded — I said, ‘This not charitable,’” said Michael West, an attorney and senior vice president of the New York Council of Nonprofits. “I’ve long questioned why these institutions get away with it. I just don’t see how it’s compliant with the IRS tax code.” West also pointed out that they don’t act like charities: “I mean, everyone knows someone with an outstanding $15,000 bill they can’t pay.”

Hospitals get their tax breaks for providing “charity care and community benefit.” But how much charity care is enough and, more important, what sort of activities count as “community benefit” and how to value them? IRS guidance released this year remains fuzzy on the issue.

Academics who study the subject have consistently found the value of many hospitals’ good work pales in comparison with the value of their tax breaks. Studies have shown that generally nonprofit and for-profit hospitals spend about the same portion of their expenses on the charity care component.

Here are some things listed as “community benefit” on hospital systems’ 990 tax forms: creating jobs; building energy-efficient facilities; hiring minority- or women-owned contractors; upgrading parks with lighting and comfortable seating; creating healing gardens and spas for patients.

All good works, to be sure, but health care?

What’s more, to justify engaging in for-profit business while maintaining their not-for-profit status, hospitals must connect the business revenue to that mission. Otherwise, they pay an unrelated business income tax.

“Their CEOs — many from the corporate world — spout drivel and turn somersaults to make the case,” said Lawton Burns, a management professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “They do a lot of profitable stuff — they’re very clever and entrepreneurial.”

The truth is that a number of not-for-profit hospitals have become wealthy diversified business organizations. The most visible manifestation of that is outsize executive compensation at many of the country’s big health systems. Seven of the 10 most highly paid nonprofit CEOs in the United States run hospitals and are paid millions, sometimes tens of millions, of dollars annually. The CEOs of the Gates and Ford foundations make far less, just a bit over $1 million.

When challenged about the generous pay packages — as they often are — hospitals respond that running a hospital is a complicated business, that pharmaceutical and insurance execs make much more. Also, board compensation committees determine the payout, considering salaries at comparable institutions as well as the hospital’s financial performance.

One obvious reason for the regulatory tolerance is that hospital systems are major employers — the largest in many states (including Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Arizona, and Delaware). They are big-time lobbying forces and major donors in Washington and in state capitals.

But some patients have had enough: In a suit brought by a local school board, a judge last year declared that four Pennsylvania hospitals in the Tower Health system had to pay property taxes because its executive pay was “eye popping” and it demonstrated “profit motives through actions such as charging management fees from its hospitals.”

A 2020 Government Accountability Office report chided the IRS for its lack of vigilance in reviewing nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit and recommended ways to “improve IRS oversight.” A follow-up GAO report to Congress in 2023 said, “IRS officials told us that the agency had not revoked a hospital’s tax-exempt status for failing to provide sufficient community benefits in the previous 10 years” and recommended that Congress lay out more specific standards. The IRS declined to comment for this column.

Attorneys general, who regulate charity at the state level, could also get involved. But, in practice, “there is zero accountability,” West said. “Most nonprofits live in fear of the AG. Not hospitals.”

Today’s big hospital systems do miraculous, lifesaving stuff. But they are not channeling Mother Teresa. Maybe it’s time to end the community benefit charade for those that exploit it, and have these big businesses pay at least some tax. Communities could then use those dollars in ways that directly benefit residents’ health.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 3 months ago

Health Care Costs, Health Care Reform, Health Industry, Hospitals

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Nursing Home Staffing Rules Prompt Pushback

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

It’s not surprising that the nursing home industry is filing lawsuits to block new Biden administration rules requiring minimum staffing at facilities that accept federal dollars. What is slightly surprising is the pushback against the rules from members of Congress. Lawmakers don’t appear to have the votes to disapprove the rule, but they might be able to force a floor vote, which could be embarrassing for the administration.

Meanwhile, Senate Democrats aim to force Republicans who proclaim support for contraceptive access to vote for a bill guaranteeing it, which all but a handful have refused to do.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Rachel Cohrs Zhang of Stat, Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico, and Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Rachel Cohrs Zhang

Stat News

Alice Miranda Ollstein

Politico

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- In suing to block the Biden administration’s staffing rules, the nursing home industry is arguing that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services lacks the authority to implement the requirements and that the rules, if enforced, could force many facilities to downsize or close.

- Anthony Fauci, the retired director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the man who advised both Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden on the covid-19 pandemic, testified this week before the congressional committee charged with reviewing the government’s pandemic response. Fauci, the subject of many conspiracy theories, pushed back hard, particularly on the charge that he covered up evidence that the pandemic began because dangerous microbes escaped from a lab in China partly funded by the National Institutes of Health.

- A giant inflatable intrauterine device was positioned near Union Station in Washington, D.C., marking what seemed to be “Contraceptive Week” on Capitol Hill. Republican senators blocked an effort by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer to force a vote on consideration of legislation to codify the federal right to contraception. Immediately after, Schumer announced a vote for next week on codifying access to in vitro fertilization services.

- Hospitals in London appear to be the latest, high-profile cyberattack victims, raising the question of whether it might be time for some sort of international cybercrime-fighting agency. In the United States, health systems and government officials are still in the very early stages of tackling the problem, and it is not clear whether Congress or the administration will take the lead.

- An FDA advisory panel this week recommended against the formal approval of MDMA, a psychedelic also known as ecstasy, to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. Members of the panel said there was not enough evidence to recommend its use. But the discussion did provide more guidance about what companies need to present in terms of trials and evidence to make their argument for approval more feasible.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Bram Sable-Smith, who reported and wrote the latest KFF Health News-NPR “Bill of the Month” feature about a free cruise that turned out to be anything but. If you have an outrageous or baffling bill you’d like to send us, you can do that here.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

- Julie Rovner: Abortion, Every Day’s “EXCLUSIVE: Health Data Breach at America’s Largest Crisis Pregnancy Org,” by Jessica Valenti.

- Alice Miranda Ollstein: The Washington Post’s “Conservative Attacks on Birth Control Could Threaten Access,” by Lauren Weber.

- Rachel Cohrs Zhang: ProPublica’s “This Mississippi Hospital Transfers Some Patients to Jail to Await Mental Health Treatment,” by Isabelle Taft, Mississippi Today.

- Sandhya Raman: Air Mail’s “Roanoke’s Requiem,” by Clara Molot.

Click to open the transcript

Transcript: Nursing Home Staffing Rules Prompt Pushback

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Mila Atmos: The future of America is in your hands. This is not a movie trailer, and it’s not a political ad, but it is a call to action. I’m Mila Atmos, and I’m passionate about unlocking the power of everyday citizens. On our podcast, Future Hindsight, we take big ideas about civic life and democracy and turn them into action items for you and me. Every Thursday we talk to bold activists and civic innovators to help you understand your power and your power to change the status quo. Find us at futurehindsight.com or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, June 6, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So here we go. We are joined today via video conference by Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Hello.

Rovner: Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning.

Rovner: And Rachel Cohrs Zhang of Stat News.

Rachel Cohrs Zhang: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Later in this episode, we’ll have my interview with KFF Health News’ Bram Sable-Smith, who reported and wrote this month’s KFF Health News/NPR “Bill of the Month.” It’s about a free cruise that turned out to be anything but. But first, this week’s news. We’re going to start this week with those controversial nursing home staffing rules.

In case you’ve forgotten, back in May, the Biden administration finalized rules that would require nursing homes that receive federal funding, which is basically all of them, to have nurses on duty 24/7/365, as well as impose other minimum staffing requirements.

The nursing home industry, which has been fighting this effort literally for decades, is doing what most big powerful health industry players do when an administration does something it doesn’t like: filing lawsuits. So what is their problem with the requirement to have sufficient staff to care for patients who, by definition, can’t care for themselves or they wouldn’t be in nursing homes?

Cohrs Zhang: Well, I think the groups are arguing that CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service] doesn’t have authority to implement these rules, and that if Congress had wanted these minimum staffing requirements, Congress should have done that and they didn’t. So they’re arguing that they’re overstepping their boundaries, and we are seeing this lawsuit again in Texas, which is a popular venue for the health care industry to try to challenge rules or legislation that they don’t like.

So, I think it isn’t a surprise that we would see these groups sue, given the financial issues at stake, given the fearmongering about facilities having to close, and just the hiring that could have to happen for a lot of these facilities. So it’s not necessarily a surprise, but it will certainly be interesting and impactful for facilities and for seniors across the nation as this plays out.

Rovner: I mean, basically one of their arguments is that there just aren’t enough people to hire, that they can’t get the number of people that they would need, and that seems to be actually pretty persuasive argument at some point, right?

Cohrs Zhang: I mean, there is controversy about why staffing shortages happen. Certainly there could be issues with the pipeline or with nursing schools, education. But I think there are also arguments that unions or workers’ rights groups would make that maybe if facilities paid better, then they would get more people to work for them. Or that people might exit the industry because of working conditions, because of understaffing, and just that makes it harder on the workers who are actually there if their workloads are too much. Or they’re expected to do more work — longer hours or overtime — or their vacation is limited, that kind of thing.

So I think it is a surprisingly controversial issue that doesn’t have an easy answer, but that’s the perspectives that we’re seeing here.

Rovner: I mean, layering onto this, it’s not just the industry versus the administration. Now Congress is getting into the act, which you rarely see. They’re talking about using the Congressional Review Act, which is something that Congress can do. But of course, when you’re in the middle of an administration that’s done it, it would get vetoed by the president. So they can’t probably do anything. Sandhya, I see you nodding your head. These members of Congress just want to make a statement here?

Raman: Yeah. So Sen. James Lankford insured the resolution earlier this week to block the rule’s implementation, and it’s mostly Republicans that have signed on, but we also have [Sen.] Joe Manchin and [Sen.] Jon Tester. But the way it stands, it doesn’t have enough folks on board yet, and it would also need to be taken up. It faces an uphill climb like many of these things.

Rovner: Somebody actually asked me yesterday though, can they do this? And the answer is yes, there is the Congressional Review Act. Yes, Congress with just a majority vote and no filibuster in the Senate can overturn an administration rule. But like I said, it usually happens when an administration changes its hands because it does have to be signed by the president and the president can veto it.

If the president vetoes it, then they would need a veto override majority, which they clearly don’t seem to have in this case. But obviously there is enough concern about this issue. I think there’s been a Congressional Review Act resolution introduced in the House too, right?

Ollstein: It’s really tough because, like Rachel said, these jobs are low-paid. They’re emotionally and physically grueling. It’s really hard to find people willing to do this work. And at the same time, the current situation seems really untenable for patients. There’s been so many reports of really horrible patient safety and hygiene issues and all kinds of stuff in part, not entirely the fault of understaffing, but not helped by understaffing certainly.

I think, like, we see on so many fronts in health care, there are attempts to do something about this situation that has become untenable, but any attempt also will piss off someone and be challenged.

Rovner: Yeah, absolutely. And we should point out that nursing homes are staffed primarily not by nurses, but by nurses aides of various training levels. So this is not entirely about a nursing shortage, it is about a shortage of workers who want to do this, as you say, very grueling and usually underpaid work.

Well, speaking of controversial things, Dr. Tony Fauci, the now-retired head of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and currently the man most conspiracy theorists hold responsible for the entire covid-19 pandemic, testified before the House Select Committee on the pandemic Monday. And not surprisingly, sparks flew. What, if anything, did we learn from this hearing?

Cohrs Zhang: The interesting part of this hearing was watching how Dr. Fauci positioned himself in response to a lot of these criticisms that have been circulating. The committee has been going through different witnesses, and specifically it criticized one of his deputies, essentially, who had some unflattering emails released showing that he appeared to be trying to delete emails or use personal accounts to avoid public records requests from journalists or other organizations …

Rovner: I’m shocked, shocked that officials would want to keep their information away from prying reporters’ eyes.

Cohrs Zhang: It’s not surprising, but it is surprising to see it in writing. But this is, again, everyone is working from home and channels of communication were changing. But I think we did see Dr. Fauci pretty aggressively distancing himself, downplaying the relationship he had with this individual and saying that they worked on research together, but he wasn’t necessarily advising agency policy.

So that’s at least how he was framing the relationship. So he definitely downplayed that. And I think an interesting comment he made — I’m curious to see what you think about this, Julie — was that he didn’t say that the lab leak theory itself was a conspiracy, but his involvement and a cover-up was a conspiracy. And so it did seem that some of the rhetoric has at least changed. He seemed more open-minded, I guess, to a lab leak theory than I expected.

Rovner: I thought he was pretty careful about that. I think it was the last thing he said, which is that we’re never really going to know. I mean, it could have been a lab leak. It could have happened. It could have been an animal from the wet market. The Chinese have not been very forthcoming with information. I personally keep wondering why we keep pounding at this.

I mean, it seems unlikely that it was a lab leak and then a conspiracy to cover it up. It clearly was one or the other, and there’s a lot of differences of opinions. And that was the last thing he said is that it could have been either. We don’t know. That’s always struck me as the, “OK, let’s talk about something else.” Anyway, let’s talk about something else.

Raman: I was just going to add, we did see a personal side to him, which I think we didn’t see as much when he was in his official role when he was talking. It was about the death threats that he and his family have been receiving when responding to a lot of the misinformation going around about that. And I thought that was striking compared to, just juxtaposed, with a lot of the other [indecipherable] with [Rep.] Marjorie Taylor Greene saying, “Oh, you’re not a real doctor.” There’s a lot of colorful protesters. And I just thought that stood out, too.

Rovner: Yeah, he did obviously, I think, relish the chance to defend himself from a lot of the charges that have been leveled at him. And I think … his wife is a prominent scientist in her own right — obviously can take care of herself — but I think he was particularly angry that there had been death threats leveled toward his grown daughters, which probably a bit out of line. Alice, you wanted to add something.

Ollstein: Yeah, I think it’s also been interesting to see the shift among Democrats on the committee over time. I think they’ve gone from an attitude of Republicans are on a total witch hunt, this is completely political, this is muddying the waters and fueling conspiracy theories and will lead to worse public health outcomes. And I think based on some of the revelations, like Rachel said about emails and such, they have come to a position of, oh, there might be some things that need investigating and need accountability in here.

But I think their frustration seems to be what it’s always been in that how will this lead to making the country better prepared in the future for the next pandemic — which may or may not already be circulating, but certainly is inevitable at some point. Either way, it’s all well and good to hold officials accountable for things they may have done, but how does that lead to making the country more prepared, improving pandemic response in the future? That’s what they feel is the missing piece here.

Rovner: Yeah. I think there was not a lot of that at this hearing, although I feel like they had to go through this maybe to get over to the other side and start thinking about what we can do in the future to avoid similar kinds of problems. And obviously you get a disease that you have no idea what to do about, and people try to muddle through the best they can. All right, now we are going to move on and we’ll talk about abortion where there is always lots of news.

Here in Washington, there is a giant inflatable IUD flying over Union Station Wednesday to highlight what seems to be Contraception Week on Capitol Hill. Not coincidentally, it’s also the anniversary this week of the Supreme Court’s 1965 ruling Griswold v. Connecticut that created the right to birth control. Alice, what are Democrats, particularly in the Senate where they’re in charge, doing to try to highlight these potential threats to contraceptive access?

Ollstein: So this vote that happened that was blocked because only two Republicans crossed the aisle to support this Right to Contraception bill — it’s the two you expect, it’s [Sen.] Lisa Murkowski and [Sen.] Susan Collins — and you’re already seeing Democrats really make hay of this. Both Democrats and their campaign arms and outside allied groups are planning to just absolutely blitz this in ads. They’re holding events in swing states related to it, and they’re going hard against individual Republicans for their votes.

I think the Republicans I talked to who voted no, they had a funny mixed message about why they were voting no on it. They were both saying that the bill was this sinister Trojan horse for forcing religious groups to promote contraception and even abortion and also gender-affirming care somehow. But also, the bill was a pointless stunt that wouldn’t really do anything because there is no threat to contraception. But also Republicans have their own rival bill to promote access to contraception.

So access to contraception isn’t a problem, but please support my bill to improve access to contraception. It’s a tough message. Whereas Democrats’ message is a lot simpler. You can argue with it on the merits, but it’s a lot simpler. They point to the fact that Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has expressed interest and actually called on the court to revisit precedents that protect the right to contraception.

Lots of states have thwarted attempts to enact protections for contraception. And a lot of anti-abortion groups have really made a big push to muddy the waters on medical understanding of what is contraception versus what is abortion, which we can get into later.

Rovner: Yes, which we will. Sandhya, did you want to add something?

Raman: Yeah, and I think that something that I would add to what Alice was saying is just how this is kind of at the same time a little bit different for the Democrats. Something that I wrote about this week was just that after the Dobbs [v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization] decision, we had the then-Democratic House vote on several different bills, but the Democrats have not really been holding this chamber-wide vote on bills related to abortion, contraception for the most part. And so this was the first time that they are stepping into that.

They’ve done the unanimous consent requests on a lot of these bills. And even just a couple months ago when talks are really heating up on IVF, there’s other things that we have to get to, appropriations and things like that, and this would just get bogged down. And they were shying away from taking floor time to do this. So I think that was an interesting move that they’re doing this now and that they’re going to vote on an IVF next week and whatever else next down the line.

Rovner: Yeah, I noticed that as soon as this bill went down, Sen. [Chuck] Schumer teed up the Right to IVF bill for a vote next week. But Alice, as you were alluding to, I mean, where this gets really uncomfortable for Republicans is that fine line between contraception and abortion. Our colleague Lauren Weber has a story about this this week [“Conservative Attacks on Birth Control Could Threaten Access,”], which is your extra credit, so why don’t you tell us about it?

Ollstein: Yeah. So she did a really great job highlighting how, especially at the state level where a lot of these battles are playing out, anti-abortion groups that are very influential are making arguments that certain forms of birth control are abortifacients. This is completely disputed by medical experts and the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] that regulates these products. They say, just to be clear about what we’re talking about, we’re talking about some forms of emergency contraception, which is taken after sex to prevent pregnancy. It is not an abortifacient. It won’t work if you’re already pregnant. It prevents pregnancy. It does not terminate a pregnancy. They are also saying this about some IUDs, intrauterine devices, and even about some hormonal birth control pills.

So there’s been pushback that Lauren detailed in her story, including from some Republicans who are trying to correct the record. But this misinformation is getting really entrenched, and I think it’s something we should all be paying attention to when it crops up, especially in the mouths of people in power.

Rovner: I mean, when I first started writing about it it was not entirely clear. There was thought that one of the ways the morning-after pill worked was by preventing implantation of a fertilized egg, which some people consider, if you consider that fertilization and not implantation, is the beginning of life. According to doctors, implantation is the beginning of pregnancy, among other things, because that’s when you can test for it.

But those who believe that fertilization is the beginning of life — and therefore something that prevents implantation is an abortion — were concerned that IUDs, and mostly progesterone-based birth control that prevented implantation, were abortifacients. Except that in the years since, it’s been shown that that’s not the case.

Ollstein: Right.

Rovner: That in fact, both IUDs and the morning-after pill work by preventing ovulation. There is no fertilized egg because there’s no egg. So they are not abortifacients. On the other hand, the FDA changed the labeling on the morning-after pill because of this. And yet the Hobby Lobby case [Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores Inc.] that the decision was written by Justice [Samuel] Alito, basically took that premise, that they were allowed to not offer these forms of contraception because they believed that they were acted as abortifacients, even though science suggests that they didn’t. It’s not something new, and it’s not something I don’t think is going to go away anytime in the near future.

Raman: I would add that it also came up in this week’s Senate Health [Committee] hearing, that line of questioning about whether or not different parts of birth control were abortifacients. Sen. [Patty] Murray did that line of questioning with Dr. Christina Francis, who’s the head of the anti-abortion obstetrician-gynecology group and went through on Plan B, IUDs and different things. And there was a back and forth of evading questions, but she did call IUDs as abortifacients, which goes back to the same thing that we’re saying.

Rovner: Right, which they have done all along.

Ollstein: Yeah. I mean, I think this really spotlights a challenge here, which is that Republicans’ response to votes like this week and things that are playing out in the state level, they’re scoffing and saying, “It’s absolutely ridiculous to suggest that Republicans are trying to ban birth control. This is completely a political concoction by Democrats to scare people into voting for them in November.”

What we’re talking about here are not bans on birth control, but there are policies that have been introduced at both the state and federal level that would make birth control, especially certain forms like we were just talking about, way harder to access. So there are proposals to carve them out of Obamacare’s contraception mandate, so they’re not covered by insurance.

That’s not a ban. You can still go pay out-of-pocket, but I remember all the people who were paying out-of-pocket for IUDs before Obamacare: hundreds and hundreds of dollars for something that is now completely free. And so what we’re seeing right now are not bans, but I think it’s important to think about the ways it would still restrict access for a lot of people.

Rovner: Before we leave the nation’s capital it seems that the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision on the abortion pill may not be the last word on the case. While it seemed likely from the oral arguments that the justices will agree that the Texas doctors who brought the case don’t have standing, there were three state attorneys general who sought to become part of the case when it was first considered back in Texas. So it would go back to Judge [Matthew] Kacsmaryk, our original judge who said that the entire abortion pill approval should be overturned. It feels like this is not the end of fighting about the abortion pill’s approval at the federal level. I mean, I assume that that’s something that the drug industry, among others, won’t be happy about.

Ollstein: Courts could find that the states don’t have standing either, that this policy does not harm them in any real way. In fact, Democratic attorneys general have argued the exact opposite, that the availability of mifepristone helps states: saves a lot of money; it prevents pregnancy; it treats people’s medical needs. So obviously, Kacsmaryk has a very long anti-abortion record and has sided with these challenges in a lot of cases. But that doesn’t mean that this would necessarily go anywhere.

But your bigger point that the Supreme Court’s upcoming ruling on mifepristone is not the end, it certainly is not. There’s going to be a lot more court challenges, some already in motion. There’s going to be state-level policy fights. There’s going to be federal-level policy fights. If Trump is elected, groups want him to do a lot of things through executive order to restrict mifepristone or remove it from the market entirely through the FDA. So yes, this is not going to be over for the foreseeable future.

Rovner: Well, meanwhile, in a case that might be over for the foreseeable future, the Texas Supreme Court last week officially rejected the case brought by 20 women who nearly died when they were unable to get timely care for pregnancy complications. The justices said in their ruling that while the women definitely did suffer, the fault lay with the doctors who declined to treat them rather than the vagueness of the state’s abortion ban. So where does that leave the debate about medical exceptions?

Ollstein: So anti-abortion groups’ response to a lot of the challenges to these abortion bans and stories about women in medical emergencies who are getting denied care and suffering real harm as a result, their response has been that there’s nothing wrong with the law. The law is perfectly clear, and that doctors are either accidentally or intentionally misinterpreting the law for political reasons. Meanwhile, doctors say it’s not clear at all. It’s not clear how honestly close to dead someone has to be in order to receive an abortion.

Rovner: And it’s not just in Texas. This is true in a bunch of states, right? The doctors don’t know …

Ollstein: In many states.

Rovner: … right? …

Ollstein: Exactly.

Rovner: … when they can intervene.

Ollstein: Right. And so I think the upcoming Supreme Court ruling on EMTALA [Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Law], which we’ve talked about, could give some indication either way of what doctors are and are not able to do, but that won’t really resolve it either. There is still so much gray area. And so patients and doctors are going to state courts to plead for clarity. They’re going to their legislatures to plead for clarity. And they’re going to state medical boards, including in Texas, to plead for clarity. And so far, they have not gotten any.

Most legislatures have been unwilling to revisit their bans and clarify or expand the exceptions even as these stories play out on the ground of doctors who say, “I know that providing an abortion for this patient is the right thing medically and ethically to do, but I’m so afraid of being hit with criminal charges that I put the patient on a plane out of state instead.” Yeah, it’s just really tough.

And so what we wrote about it is we keep talking about doctors being torn between conflicting state and federal law, and that’s absolutely true, but what we dug into is that the state law just looms so much larger than the federal laws. So when you’re weighing, should I maybe violate EMTALA or should I maybe violate my state’s ban, they’re not going to want to violate their state’s ban because that means jail time, that means losing their license, that means having their freedom and their livelihood taken away.

Whereas an EMTALA violation may or may not mean a fine somewhere down the road. The enforcement has not been as aggressive at the federal level from the Biden administration as a lot of doctors would like it to be. And so, in that environment, they’re really deferring to the state law, and that means some people are not getting care that they maybe need.

Rovner: I say in the meantime, we had yet another jury just last week about a woman who had a miscarriage and could not get a D&C [dilation and curettage procedure] basically. When she went in there was no fetal heartbeat, but she ended up miscarrying at home and almost dying. She was sent away, I believe, from three different facilities. This continues to happen because doctors are concerned about when it is appropriate for them to intervene. And they seem, you’re right, to be leaning towards the “let’s not get in trouble with the state” law, so let’s wait to provide care as long as we think we can.

Well, moving on, we have two stories this week about efforts to treat post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly in military veterans. On Tuesday, an FDA advisory committee recommended against approval of the psychedelic MDMA, better known as ecstasy, for the treatment of PTSD. My understanding is that the panel didn’t reject the idea outright that this could be helpful, only that there isn’t enough evidence yet to approve it. Was I reading that right? Rachel, you guys covered this pretty closely.

Cohrs Zhang: Yes. Yeah, my colleagues did cover this. Certainly I think what’s a discouraging sign, I don’t think there’s any way around it, for some of these companies that are looking at psychedelics and trying to figure out some sort of approval pathway for conditions like PTSD.

One of my colleagues, Meghana Keshavan, she chatted with a dozen companies yesterday and they were trying to put a positive spin on it, that having some opinion or some discussion of a treatment like this by the advisory committee could lay out more clear standards for what companies would have to present in order to get something approved. So I think obviously they have a vested interest in spinning this positively.

But it is a very innovative space and certainly was a short-term setback. But it certainly isn’t a long-term issue if some of these companies are able to present stronger evidence or better trial design. I think there were some questions about whether trial participants actually could figure out whether they were placebo or not, which if you’re taking psychedelic drugs, yeah, that’s kind of a challenge in terms of trial design.

So I think there are some interesting questions, and I am confident that this’ll be something the FDA and industry is going to have to figure out in a space that’s new like this.

Rovner: Yeah, it’s been interesting to follow. Well, in something that does seem to help, one of the first controlled studies of service dogs to treat PTSD has found that man’s best friend can be a therapist as well. Those veterans who got specially trained dogs showed much more improvement in their symptoms than those who were on the doggy wait list as determined by professionals who didn’t know who had the dogs and who didn’t. So pet therapy for the win here?

Raman: I mean, this is the biggest study of this kind that we’ve had so far, and it seems promising. I think one thing will be interesting is if there’s more research, if this would change policy down the line for the VA [Department of Veterans Affairs] or other agencies to be able to get these kinds of service dogs in the hands of more vets.

Rovner: Yeah, I know there’s a huge demand for these kinds of service dogs. I know a lot of people who basically have started training service dogs for veterans. Obviously they were able to do this study because there was a long wait list. They were able to look at people who were waiting but hadn’t gotten a dog yet. So at least in the short term, possibly some help for some people.

Finally this week, in a segment I’m calling “Misery Loves Company,” it’s not just the U.S. where big health systems are getting cyberhacked. Across the pond, quoting here from the BBC, major hospitals in London have declared a critical incident after a cyberattack led to operations being canceled and emergency patients being diverted elsewhere. This sounds painfully familiar.

Maybe we need an international cybercrime fighting agency. Is there one? Is there at least, do we know, is there a task force working on this? Obviously the bigger, more centralized your health care system, the bigger problem this becomes, as we saw with Change Healthcare belonging to United[Healthcare], and this is now … I guess it’s a contractor that works for the NHS [National Health Service]. You can see the potential for really bad stuff here.

Cohrs Zhang: That’s a good question about some international standards, Julie, but I think what we have seen is Sen. Ron Wyden, who leads the Senate Finance Committee, did write to HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] this week and asked HHS to add to multiple-factor authentication as a condition of participation for some of these facilities to try to institute standards that way.

And again, I think there are questions about how much HHS can actually do, but I think it’s a signal that Congress might not want to do anything or think they can do anything if they’re asking the administration to do something here. But we’re still in the very early stages of systems viewing this as worthy of investment and just education about some of the best practices here.

Yeah, certainly it’s going to be a business opportunity for some consulting firms to help these hospitals increase their cybersecurity measures and certainly will be a global market if we see these attacks continue in other places, too.

Rovner: Maybe our health records will be as protected as our Spotify accounts. It would apparently be a step forward. All right, well, that is the news for this week. Now we will play my “Bill of the Month” interview with Bram Sable-Smith, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am pleased to welcome back to the podcast my KFF Health News colleague Bram Sable-Smith, who reported and wrote the latest KFF Health News-NPR “Bill of the Month” about a free cruise that turned out to be anything but. Welcome back to the podcast, Bram.

Bram Sable-Smith: Thanks for having me.

Rovner: So tell us about this month’s patient, who he is, and what happened to him. This is one of the wilder Bills of the Month, I think.

Sable-Smith: Right. So his name is Vincent Wasney. He lives in Saginaw, Michigan. Never been on an airplane before, neither had his [fiancée], Sarah. But when they bought their first house in 2019, their Realtor, as a gift, gifted them tickets for a cruise. My Realtor gave me a tote bag. So, what a Realtor, first of all! What an incredible gift.

Rovner: My Realtor gave me a wine opener, which I do still use.

Sable-Smith: If it sailed to the Caribbean, it’d be equivalent. So their cruise got delayed because of the pandemic, but they set sail in December 2022. And they were having a great time. One of the highlights of their trip was they went to this private island called CocoCay for Royal Caribbean guests, and it included an excursion to go swimming with pigs.

Rovner: Wild pigs, right?

Sable-Smith: Wild pigs, a big fancy water park, all kinds of food. They were having a great time. But it’s also on that island that Vincent started feeling off. And so in the past, Vincent has had seizures. About 10 years earlier, he had had a few seizures. They decided he was probably epileptic, and he was on medicine for a while. He went off the medicine because they were worried about liver damage, and he’d been relatively seizure-free for a long time. It’d been a long time since he’d had a seizure.

But when he was on that island having a great time, it’s when he started to feel off. And when they got back on the cruise ship for the last full day of the cruise, he had a seizure in his room. And he was taken down to the medical center on the cruise ship and he was observed. He was given fluids for a while, and then sent back to his room, where he had a second seizure. Once again, went down to the medical center on the ship, where he had a third seizure. It was time to get him off the boat. He needed to get onto land and go to a hospital. And so they were close enough to land that they were able to do the evacuation by boat instead of having to do something like a helicopter to do a medevac that way. And so a rescue boat came to the ship. He was lowered off the ship. He was in a stretcher and it was lowered down to the rescue boat by a rope.

His fiancée, Sarah, climbed down a rope ladder to get into the boat as well to go with them to land. And then he was taken to land in an ambulance ride to the hospital, et cetera. But, before they were allowed to disembark, they were given their bill and told “It’s time to pay this. You have to pay this bill.”

Rovner: And how much was it?

Sable-Smith: So the bill for the medical services was $2,500. This was a free cruise. They had budgeted to pay for internet, $150 for internet. They had budgeted to pay for their alcoholic drinks. They had budgeted to pay for their tips. So they had saved up a few hundred dollars, which is what they thought would be their bill at the end of this cruise. Now, that completely exploded into this $2,500 bill just for medical expenses alone.

And as they’re waiting to evacuate the ship, they’re like, “We can’t pay this. We don’t have this money.” So that led to some negotiations. They ended up basically taking all the money out of their bank accounts, including their mortgage payment. They maxed out Vincent’s credit card, but they were still $1,000 short. And they later learned once they were on land that Vincent’s credit card had been overdrafted by $1,000 to cover that additional expense.

Rovner: So it turns out that he was uninsured at the time, and we’ll talk about that in a minute. But even if he had had insurance, the cruise ship wasn’t going to let him off the boat until he paid in full, even though it was an emergency? Did I read that right?

Sable-Smith: That’s certainly the feeling that they had at the time. When Vincent was short the $1,000, eventually they were let off the ship, but they did end up, as we said, getting that credit card overdrafted. But I think what’s important to note here is that even though he was uninsured at the time, even if he had had insurance, and even if he had had travel insurance, which he also did not have at the time, which we can talk about, he still would’ve been required to pay upfront and then submit the receipts later to try to get reimbursed for the payments.

And that’s because on the cruise’s website, they explain that they do not accept “land-based health insurance plans” when they’re on the vessel.

Rovner: In fact, as you mentioned, a lot of health insurance doesn’t cover care on a cruise ship or, in fact, anywhere outside the United States. So lots of people buy travel insurance in case they have a medical emergency. Why didn’t they?

Sable-Smith: So travel insurance is often purchased when you purchase the tickets. You’ll buy a ticket to the cruise and then it will prompt you, say, “Hey, do you want some travel insurance to protect you while you’re on this ship?” And that’s the way that most people are buying travel insurance. Well, remember, this cruise was a gift from their realtors, so they never bought the ticket. So they never got that prompting to say, “Hey, time to buy some travel insurance to protect yourself on the trip.”

And again, these were inexperienced travelers. They’d never been on an airplane before. The furthest either one of them had been from Michigan was Vincent went to Washington, D.C., one time on a school trip. And so they didn’t really know what travel insurance was. They knew it existed. But as Vincent explained, he said, “I thought this was for lost luggage and trip cancellations. I didn’t realize that this was something for medical expenses you might incur when you’re out at sea.”

Rovner: And it’s really both. I mean, it is for lost luggage and cancellation, right?

Sable-Smith: And it is for lost luggage and cancellation. Yeah, that’s right.

Rovner: So what eventually happened to Vincent and what eventually happened to the bill?

Sable-Smith: Well, once he got taken to the hospital, he got an additional bill, or actually several additional bills, one from the hospital, two from a couple doctors who saw him at the hospital who billed separately, and also one from the ambulance services. As we know, he had already drained his bank account and maxed out his credit card and had it overdrafted to cover the expenses on the ship. So he was working on paying those off. And then for the additional bills he incurred on land, he had set up payment plans, really small ones, $25, $50 a month, but going to four separate entities.

He actually missed a couple payments on his bill to the hospital, and that ended up getting sent to collections. Again, none of these are charging interest, but these are still quite some burdens. And so he was paying them off bit by bit by bit. He set up a GoFundMe campaign, which is something that a lot of people end up doing who never expect to have to cover these kinds of emergency expenses, or reach out publicly for help like that. And they got quite a bit of help from family and friends. Including, Vincent picked up Frisbee golf during the pandemic, and he’s made quite a lot of good friends that way. And that community really came through for them as well. So with those GoFundMe payments, they were able to make their house payment. It was helpful with some of these bills that they had lingering leftover from the cruise.

Rovner: So what’s the takeaway here, other than that nothing that seems free is ever really free?

Sable-Smith: Yeah, right. Well, the takeaway is to be informed before you leave about a plan for how are you going to cover medical expenses when you’re going traveling. I think this is something that a lot of people are going to be doing this summer, going on vacations. I’ve got vacations planned. What’s your plan for covering medical expenses? And if you’re leaving the country, if you’re going on a cruise, someplace where your land-based American health insurance might not cover you, you should consider travel insurance.

And when you’re considering travel insurance, they come in all sorts of varieties. So you want to make sure that they’re going to cover your particular cases. So some plans, for example, won’t cover pre-existing conditions. Some plans won’t cover care for risky activities like rock climbing. So you want to know what you’re going to be doing during your trip, and you want to make sure when you’re purchasing travel insurance to find a plan that’s going to cover your particular needs.

Rovner: Very well explained. Bram Sable-Smith, thank you very much.

Sable-Smith: Always a pleasure.

Rovner: And now it’s time for our extra credit segment. That’s when we each recommend a story we read this week we think you should read, too. As always, don’t worry if you miss it. We will post the links on the podcast page at kffhealthnews.org and in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Alice, you’ve gone already. Sandhya, why don’t you go next?

Raman: So my extra credit is “Roanoke’s Requiem,” and it’s an Air Mail from Clara Molot. And this is a really interesting piece. So at least 16 alumni from the classes of 2011 to 2019 of Roanoke have been diagnosed with cancer since 2010, which is a much higher rate when compared to the rate for 20-somethings in the U.S. and 15-times-higher mortality rate. And so the piece does some looking at some of the work that’s being done to uncover why this is happening.

Rovner: It’s quite a scary story. Rachel?

Cohrs Zhang: Yes. So the story I chose, it was co-published by ProPublica in Mississippi Today. The headline is “This Mississippi Hospital Transfers Some Patients to Jail to Await Mental Health Treatment,” by Isabelle Taft. And I mean, truly such a harrowing story of … obviously we know that there’s capacity issues with mental health treatment, but the idea that patients would be involuntarily committed, go to a hospital, and then be transferred to a jail having committed no crime, having no recourse.

I mean, some of these detentions happened. It was like two months long where these patients who are already suffering are then thrown out of their comfortable environments into jail as they awaited county facilities to open up spots for them. And I think the story also did a good job of pointing out that other jurisdictions had found other solutions to this other than placing suffering people in jail. So yeah, it just felt like it was a really great classic example of investigative journalism that’ll have an impact.

Rovner: Local investigative journalism — not just investigative journalism — which is really rare, yet it was a really good piece. Well, my extra credit this week is from Jessica Valenti, who writes a super-helpful newsletter called Abortion, Every Day. Usually it’s an aggregation of stories from around the country, but this week she also has her own exclusive [“EXCLUSIVE: Health Data Breach at America’s Largest Crisis Pregnancy Org,”] about how Heartbeat International, which runs the nation’s largest network of crisis pregnancy centers, is collecting and sharing private health data, including due dates, dates of last menstrual periods, addresses, and even family living arrangements.

Isn’t this a violation of HIPAA, you may ask? Well, probably not, because HIPAA only applies to health care providers and insurers and the vast majority of crisis pregnancy centers don’t deliver medical care. You don’t need a medical license to give a pregnancy test or even do an ultrasound. Among other things, personal health data has been used for training sales staff, and until recently was readily available to anyone on the web without password protection. It’s a pretty eye-opening story.

All right, that is our show. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate it if you left us a review; that helps other people find us, too. Special thanks as always to our technical guru, Francis Ying, and our fill-in editor this week, Stephanie Stapleton. As always, you can email us your comments or questions. We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org, or you can still find me at X, I’m at @jrovner. Sandhya?

Raman: @SandhyaWrites.

Rovner: Alice?

Ollstein: @AliceOllstein.

Rovner: Rachel?

Cohrs Zhang: @rachelcohrs.

Rovner: We will be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Stephanie Stapleton

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 4 months ago

COVID-19, Health Industry, Multimedia, Biden Administration, CMS, Contraception, FDA, Hospitals, KFF Health News' 'What The Health?', Nursing Homes, Podcasts, U.S. Congress

Tennessee Gives This Hospital Monopoly an A Grade — Even When It Reports Failure

A Tennessee agency that is supposed to hold accountable and grade the nation’s largest state-sanctioned hospital monopoly awards full credit on dozens of quality-of-care measurements as long as it reports any value — regardless of how its hospitals actually perform.

Ballad Health, a 20-hospital system in northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia, has received A grades and an annual stamp of approval from the Tennessee Department of Health. This has occurred as Ballad hospitals consistently fall short of performance targets established by the state, according to health department documents.

Because the state’s scoring rubric largely ignores the hospitals’ performance, only 5% of Ballad’s final score is based on actual quality of care, and Ballad has suffered no penalty for failing to meet the state’s goals in about 50 areas — including surgery complications, emergency room speed, and patient satisfaction.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” said Ron Allgood, 75, of Kingsport, Tennessee, who said he had a heart attack in a Ballad ER in 2022 after waiting for three hours with chest pains. “It seems that nobody listens to the patients.”

Ballad Health was created six years ago after Tennessee and Virginia lawmakers waived federal anti-monopoly laws so two competing hospital companies could merge. The monopoly agreement established two quality measures to compare Ballad’s care against the state’s baseline expectations: about 17 “target” measures, on which hospitals are expected to improve and their performance factors into their grade; and more than 50 “monitoring” measures, which Ballad must report, but how the hospitals perform on them is not factored into Ballad’s grade.

Ballad has failed to meet the baseline values on 75% or more of all quality measures in recent years — and some are not even close — according to reports the company has submitted to the health department.

Since the merger, Ballad has become the only option for hospital care for most of about 1.1 million residents in a 29-county region at the nexus of Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina. Critics are vocal. Protesters rallied outside a Ballad hospital for months. For years, longtime residents like Allgood have alleged Ballad’s leadership has diminished the hospitals they’ve relied on their entire lives.

“It’s a shadow of the hospital we used to have,” Allgood said.

And yet, every year since the merger, the Tennessee health department has reported that the benefits of the hospital merger outweigh the risks of a monopoly, and that Ballad “continues to provide a Public Advantage.” Tennessee has also given Ballad an A grade in every year but two, when the scoring system was suspended due to the covid-19 pandemic and no grade issued.

The department’s latest report, released this month, awarded Ballad 93.6 of 100 possible points, including 15 points just for reporting the monitoring measures. If Tennessee rescored Ballad based on its performance, its score would drop from 93.6 to about 79.7, based on the scoring rubric described in health department documents. Tennessee considers scores of 85 or higher to be “satisfactory,” the documents state.

Larry Fitzgerald, who monitored Ballad for the Tennessee government before retiring this year, said it was obvious the state’s scoring rubric should be changed.

Fitzgerald likened Ballad to a student getting 15 free points on a test for writing any answer.

“Do I think Ballad should be required to show improvement on those measures? Yes, absolutely,” Fitzgerald said. “I think any human being you spoke with would give the same answer.”

Ballad Health declined to comment. Tennessee Department of Health spokesperson Dean Flener declined an interview request and directed all questions about Ballad to the Tennessee Attorney General’s Office, which also has a role in regulating the monopoly. Amy Wilhite, a spokesperson for the AG’s office, directed those questions back to the health department and provided documents showing it is the agency responsible for how Ballad is scored.

The Virginia Department of Health, which is also supposed to perform “active supervision” of Ballad as part of the monopoly agreement, has fallen several years behind schedule. Its most recent assessment of the company was for fiscal year 2020, when it found that the benefits of the monopoly “outweigh the disadvantages.” Erik Bodin, a Virginia official who oversees the agreement, said more recent reports are not yet ready to be released.

Ballad Health was formed in 2018 after state officials approved the nation’s biggest so-called Certificate of Public Advantage, or COPA, agreement, allowing a merger of the Tri-Cities region’s only two hospital systems — Mountain States Health Alliance and Wellmont Health System. Nationwide, COPAs have been used in about 10 hospital mergers over the past three decades, but none has involved as many hospitals as Ballad’s.

The Federal Trade Commission has warned that hospital monopolies lead to increased prices and decreased quality of care. To offset the perils of Ballad’s monopoly, officials required the new company to agree to more robust regulation by state health officials and a long list of special conditions, including the state’s quality-of-care measurements.

Ballad failed to meet the baseline on about 80% of those quality measures from July 2021 to June 2022, according to a report the company submitted to the health department. The following year, Ballad fell short on about 75% of the quality measures, and some got dramatically worse, another company report shows.

For example, the median time Ballad patients spend in the ER before being admitted to the hospital has risen each year and is now nearly 11 hours, according to the latest Ballad report. That’s more than three times what it was when the monopoly began, and more than 2.5 times the state baseline.

And yet Ballad’s grade is not lowered by the lack of speed in its ERs.

Fitzgerald, Tennessee’s former Ballad monitor, who previously served as an executive in the University of Virginia Health System, said a hospital company with competitors would have more reason than Ballad to improve its ER speeds.

“When I was at UVA, we monitored this stuff passionately because — and I think this is the key point here — we had competition,” Fitzgerald said. “And if we didn’t score well, the competition took advantage.”

Midwest correspondent Samantha Liss contributed to this report.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 5 months ago