In Bustling NYC Federal Building, HHS Offices Are Eerily Quiet

NEW YORK — On a recent visit to Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan, some floors in the mammoth office building bustled with people seeking services or facing legal proceedings at federal agencies such as the Social Security Administration and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In the lobby, dozens of people took photos to celebrate becoming U.S. citizens.

At the Department of Homeland Security, a man was led off the elevator in handcuffs.

But the area housing the regional office of the Department of Health and Human Services was eerily quiet.

In March, HHS announced it would close five of its 10 regional offices as part of a broad restructuring to consolidate the department’s work and reduce the number of staff by 20,000, to 62,000. The HHS Region 2 office in New York City, which has served New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, was among those getting the ax.

Public health experts and advocates say that HHS regional offices, like the one in New York City, form the connective tissue between the federal government and many locally based services. Whether ensuring local social service programs like Head Start get their federal grants, investigating Medicare claims complaints, or facilitating hospital and health system provider enrollment in Medicare and Medicaid programs, regional offices provide a key federal access point for people and organizations. Consolidating regional offices could have serious consequences for the nation’s public health system, they warn.

“All public health is local,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “When you have relative proximity to the folks you’re liaising to, they have a sense of the needs of those communities, and they have a sense of the political issues that are going on in these communities.”

The other offices slated to close are in Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Seattle. Together, the five serve 22 states and a handful of U.S. territories. Services for the shuttered regional offices will be divvied up among the remaining regional offices in Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Kansas City, and Philadelphia.

The elimination of regional HHS offices has already had an outsize impact on Head Start, a long-standing federal program that provides free child care and supportive services to children from many of the nation’s poorest families. It is among the examples cited in the lawsuit against the federal government challenging the HHS restructuring brought by New York, 18 other states, and the District of Columbia, which notes that, as a result, “many programs are at imminent risk of being forced to pause or cease operations.”

The HHS site included a regional Head Start office that was closed and laid off staff last month. The Trump administration had sought to wipe out funding for Head Start, according to a draft budget document that outlines dramatic cuts at HHS, which Congress would need to approve. Recent news reports indicate the administration may be stepping back from this plan; however, other childhood and early-development programs could still be on the chopping block.

Bonnie Eggenburg, president of the New Jersey Head Start Association, said her organization has long relied on the HHS regional office to be “our boots on the ground for the federal government.” During challenging times, such as the covid-19 pandemic or Hurricanes Sandy and Maria, the regional office helped Head Start programs design services to meet the needs of children and families. “They work with us to make sure we have all the support we can get,” she said.

In recent weeks, payroll and other operational payments have been delayed, and employees have been asked to justify why they need the money as part of a new “Defend the Spend” initiative instituted by the Elon Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency, created by President Donald Trump through an executive order.

“Right now, most programs don’t have anyone to talk to and are unsure as to whether or not that notice of award is coming through as expected,” Eggenburg said.

HHS regional office employees who worked on Head Start helped providers fix technical issues, address budget questions, and discuss local issues, like the city’s growing population of migrant children, said Susan Stamler, executive director of United Neighborhood Houses. Based in New York City, the organization represents dozens of neighborhood settlement houses — community groups that provide services to local families such as language classes, housing assistance, and early-childhood support, including some Head Start programs.

“Today, the real problem is people weren’t given a human contact,” she said of the regional office closure. “They were given a website.”

To Stamler, closing the regional Head Start hub without a clear transition plan “demonstrates a lack of respect for the people who are running these programs and services,” while leaving families uncertain about their child care and other services.

“It’s astonishing to think that the federal government might be reexamining this investment that pays off so deeply with families and in their communities,” she said.

Without regional offices, HHS will be less informed about which health initiatives are needed locally, said Zach Hennessey, chief strategy officer of Public Health Solutions, a nonprofit provider of health services in New York City.

“Where it really matters is within HHS itself,” he said. “Those are the folks that are now blind — but their decisions will ultimately affect us.”

Dara Kass, an emergency physician who was the HHS Region 2 director under the Biden administration, described the job as being an ambassador.

“The office is really about ensuring that the community members and constituents had access to everything that was available to them from HHS,” Kass said.

At HHS Region 2, division offices for the Administration for Community Living, the FDA’s Office of Inspections and Investigations, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration have already closed or are slated to close, along with several other division offices.

HHS did not provide an on-the-record response to a request for comment but has maintained that shuttering regional offices will not hurt services.

Under the reorganization, many HHS agencies are either being eliminated or folded into other agencies, including the recently created Administration for a Healthy America, under HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

“We aren’t just reducing bureaucratic sprawl. We are realigning the organization with its core mission and our new priorities in reversing the chronic disease epidemic,” Kennedy said in a press release announcing the reorganization.

Regional office staffers were laid off at the beginning of April. Now there appears to be a skeleton crew shutting down the offices. On a recent day, an Administration for Children and Families worker who answered a visitor’s buzz at the entrance estimated that only about 15 people remained. When asked what’s next, the employee shrugged.

The Trump administration’s downsizing effort will also eliminate six of 10 regional outposts of the HHS Office of the General Counsel, a squad of lawyers supporting the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other agencies in beneficiary coverage disputes and issues related to provider enrollment and participation in federal programs.

Unlike private health insurance companies, Medicare is a federal health program governed by statutes and regulations, said Andrew Tsui, a partner at Arnall Golden Gregory who has co-written about the regional office closings.

“When you have the largest federal health insurance program on the planet, to the extent there could be ambiguity or appeals or grievances,” Tsui said, “resolving them necessarily requires the expertise of federal lawyers, trained in federal law.”

Overall, the loss of the regional HHS offices is just one more blow to public health efforts at the state and local levels.

State health officials are confronting the “total disorganization of the federal transition” and cuts to key federal partners like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CMS, and the FDA, said James McDonald, the New York state health commissioner.

“What I’m seeing is, right now, it’s not clear who our people ought to contact, what information we’re supposed to get,” he said. “We’re just not seeing the same partnership that we so relied on in the past.”

Healthbeat is a nonprofit newsroom covering public health published by Civic News Company and KFF Health News. Sign up for its newsletters here.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

5 months 1 week ago

Medicaid, Medicare, Postcards, Public Health, Healthbeat, HHS, New York, Trump Administration

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

After narrowly passing a budget resolution this spring foreshadowing major Medicaid cuts, Republicans in Congress are having trouble agreeing on specific ways to save billions of dollars from a pool of funding that pays for the program without cutting benefits on which millions of Americans rely. Moderates resist changes they say would harm their constituents, while fiscal conservatives say they won’t vote for smaller cuts than those called for in the budget resolution. The fate of President Donald Trump’s “one big, beautiful bill” containing renewed tax cuts and boosted immigration enforcement could hang on a Medicaid deal.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration surprised those on both sides of the abortion debate by agreeing with the Biden administration that a Texas case challenging the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone should be dropped. It’s clear the administration’s request is purely technical, though, and has no bearing on whether officials plan to protect the abortion pill’s availability.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Anna Edney of Bloomberg News, Maya Goldman of Axios, and Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Anna Edney

Bloomberg News

Maya Goldman

Axios

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- Congressional Republicans are making halting progress on negotiations over government spending cuts. As hard-line House conservatives push for deeper cuts to the Medicaid program, their GOP colleagues representing districts that heavily depend on Medicaid coverage are pushing back. House Republican leaders are eying a Memorial Day deadline, and key committees are scheduled to review the legislation next week — but first, Republicans need to agree on what that legislation says.

- Trump withdrew his nomination of Janette Nesheiwat for U.S. surgeon general amid accusations she misrepresented her academic credentials and criticism from the far right. In her place, he nominated Casey Means, a physician who is an ally of HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s and a prominent advocate of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

- The pharmaceutical industry is on alert as Trump prepares to sign an executive order directing agencies to look into “most-favored-nation” pricing, a policy that would set U.S. drug prices to the lowest level paid by similar countries. The president explored that policy during his first administration, and the drug industry sued to stop it. Drugmakers are already on edge over Trump’s plan to impose tariffs on drugs and their ingredients.

- And Kennedy is scheduled to appear before the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee next week. The hearing would be the first time the secretary of Health and Human Services has appeared before the HELP Committee since his confirmation hearings — and all eyes are on the committee’s GOP chairman, Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a physician who expressed deep concerns at the time, including about Kennedy’s stances on vaccines.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and co-wrote the latest KFF Health News’ “Bill of the Month” installment, about an unexpected bill for what seemed like preventive care. If you have an outrageous, baffling, or infuriating medical bill you’d like to share with us, you can do that here.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: NPR’s “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured,” by Andrea Hsu.

Maya Goldman: Stat’s “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph.

Anna Edney: Bloomberg News’ “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare,” by Zachary R. Mider and Zeke Faux.

Sandhya Raman: The Louisiana Illuminator’s “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” by Anna Claire Vollers.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- ProPublica’s series “Life of the Mother: How Abortion Bans Lead to Preventable Deaths,” by Kavitha Surana, Lizzie Presser, Cassandra Jaramillo, and Stacy Kranitz, and the winner of the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for public service journalism.

- The New York Times’ “G.O.P. Targets a Medicaid Loophole Used by 49 States To Grab Federal Money,” by Margot Sanger-Katz and Sarah Kliff.

- KFF Health News’ “Seeking Spending Cuts, GOP Lawmakers Target a Tax Hospitals Love to Pay,” by Phil Galewitz.

- Axios’ “Out-of-Pocket Drug Spending Hit $98B in 2024: Report,” by Maya Goldman.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, May 8, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via a videoconference by Anna Edney of Bloomberg News.

Anna Edney: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Maya Goldman of Axios News.

Maya Goldman: Great to be here.

Rovner: And Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning, everyone.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have my “Bill of the Month” interview with my KFF Health News colleague Lauren Sausser. This month’s patient got preventive care they assumed would be covered by their Affordable Care Act health plan, except it wasn’t. But first, this week’s news.

We’re going to start on Capitol Hill, where Sandhya is coming directly from, where regular listeners to this podcast will be not one bit surprised that Republicans working on President [Donald] Trump’s one “big, beautiful” budget reconciliation bill are at an impasse over how and how deeply to cut the Medicaid program. Originally, the House Energy and Commerce Committee was supposed to mark up its portion of the bill this week, but that turned out to be too optimistic. Now they’re shooting for next week, apparently Tuesday or so, they’re saying, and apparently that Memorial Day goal to finish the bill is shifting to maybe the Fourth of July? But given what’s leaking out of the closed Republican meetings on this, even that might be too soon. Where are we with these Medicaid negotiations?

Raman: I would say a lot has been happening, but also a lot has not been happening. I think that anytime we’ve gotten any little progress on knowing what exactly is at the top of the list, it gets walked back. So earlier this week we had a meeting with a lot of the moderates in Speaker [Mike] Johnson’s office and trying to get them on board with some of the things that they were hesitant about, and following the meeting, Speaker Johnson had said that two of the things that have been a little bit more contentious — changing the federal match for the expansion population and instituting per capita caps for states — were off the table. But the way that he phrased it is kind of interesting in that he said stay tuned and that it possibly could change.

And so then yesterday when we were hearing from the Energy and Commerce Committee, it seemed like these things are still on the table. And then Speaker Johnson has kind of gone back on that and said, I said it was likely. So every time we kind of have any sort of change, it’s really unclear if these things are in the mix, outside the mix. When we pulled them off the table, we had a lot of the hard-line conservatives get really upset about this because it’s not enough savings. So I think any way that you push it with such narrow margins, it’s been difficult to make any progress, even though they’ve been having a lot of meetings this week.

Rovner: One of the things that surprised me was apparently the Senate Republicans are weighing in. The Senate Republicans who aren’t even set to make Medicaid cuts under their version of the budget resolution are saying that the House needs to go further. Where did that come from?

Raman: It’s just been a difficult process to get anything across. I mean, in the House side, a lot of it has been, I think, election-driven. You see the people that are not willing to make as many concessions are in competitive districts. The people that want to go a little bit more extreme on what they’re thinking are in much more safe districts. And then in the Senate, I think there’s a lot more at play just because they have longer terms, they have more to work with. So some of the pushback has been from people that it would directly affect their states or if the governors have weighed in. But I think that there are so many things that they do want to get done, since there is much stronger agreement on some of the immigration stuff and the taxes that they want to find the savings somewhere. If they don’t find it, then the whole thing is moot.

Rovner: So meanwhile, the Congressional Budget Office at the request of Democrats is out with estimates of what some of these Medicaid options would mean for coverage, and it gives lie to some of these Republican claims that they can cut nearly a trillion dollars from Medicaid without touching benefits, right? I mean all of these — and Maya, your nodding.

Goldman: Yeah.

Rovner: All of these things would come with coverage losses.

Goldman: Yeah, I think it’s important to think about things like work requirements, which has gotten a lot of support from moderate Republicans. The only way that that produces savings is if people come off Medicaid as a result. Work requirements in and of themselves are not saving any money. So I know advocates are very concerned about any level of cuts. I talked to somebody from a nursing home association who said: We can’t pick and choose. We’re not in a position to pick and choose which are better or worse, because at this point, everything on the table is bad for us. So I think people are definitely waiting with bated breath there.

Rovner: Yeah, I’ve heard a lot of Republicans over the last week or so with the talking points. If we’re just going after fraud and abuse then we’re not going to cut anybody’s benefits. And it’s like — um, good luck with that.

Goldman: And President Trump has said that as well.

Rovner: That’s right. Well, one place Congress could recoup a lot of money from Medicaid is by cracking down on provider taxes, which 49 of the 50 states use to plump up their federal Medicaid match, if you will. Basically the state levies a tax on hospitals or nursing homes or some other group of providers, claims that money as their state share to draw down additional federal matching Medicaid funds, then returns it to the providers in the form of increased reimbursement while pocketing the difference. You can call it money laundering as some do, or creative financing as others do, or just another way to provide health care to low-income people.

But one thing it definitely is, at least right now, is legal. Congress has occasionally tried to crack down on it since the late 1980s. I have spent way more time covering this fight than I wish I had, but the combination of state and health provider pushback has always prevented it from being eliminated entirely. If you want a really good backgrounder, I point you to the excellent piece in The New York Times this week by our podcast pals Margot Sanger-Katz and Sarah Kliff. What are you guys hearing about provider taxes and other forms of state contributions and their future in all of this? Is this where they’re finally going to look to get a pot of money?

Raman: It’s still in the mix. The tricky thing is how narrow the margins are, and when you have certain moderates having a hard line saying, I don’t want to cut more than $500 billion or $600 billion, or something like that. And then you have others that don’t want to dip below the $880 billion set for the Energy and Commerce Committee. And then there are others that have said it’s not about a specific number, it’s what is being cut. So I think once we have some more numbers for some of the other things, it’ll provide a better idea of what else can fit in. Because right now for work requirements, we’re going based on some older CBO [Congressional Budget Office] numbers. We have the CBO numbers that the Democrats asked for, but it doesn’t include everything. And piecing that together is the puzzle, will illuminate some of that, if there are things that people are a little bit more on board with. But it’s still kind of soon to figure out if we’re not going to see draft text until early next week.

Goldman: I think the tricky thing with provider taxes is that it’s so baked into the way that Medicaid functions in each state. And I think I totally co-sign on the New York Times article. It was a really helpful explanation of all of this, and I would bet that you’ll see a lot of pushback from state governments, including Republicans, on a proposal that makes severe changes to that.

Rovner: Someday, but not today, I will tell the story of the 1991 fight over this in which there was basically a bizarre dealmaking with individual senators to keep this legal. That was a year when the Democrats were trying to get rid of it. So it’s a bipartisan thing. All right, well, moving on.

It wouldn’t be a Thursday morning if we didn’t have breaking federal health personnel news. Today was supposed to be the confirmation hearing for surgeon general nominee and Fox News contributor Janette Nesheiwat. But now her nomination has been pulled over some questions about whether she was misrepresenting her medical education credentials, and she’s already been replaced with the nomination of Casey Means, the sister of top [Health and Human Services] Secretary [Robert F.] Kennedy [Jr.] aide Calley Means, who are both leaders in the MAHA [“Make America Healthy Again”] movement. This feels like a lot of science deniers moving in at one time. Or is it just me?

Edney: Yeah, I think that the Meanses have been in this circle, names floated for various things at various times, and this was a place where Casey Means fit in. And certainly she espouses a lot of the views on, like, functional medicine and things that this administration, at least RFK Jr., seems to also subscribe to. But the one thing I’m not as clear on her is where she stands with vaccines, because obviously Nesheiwat had fudged on her school a little bit, and—

Rovner: Yeah, I think she did her residency at the University of Arkansas—

Edney: That’s where.

Rovner: —and she implied that she’d graduated from the University of Arkansas medical school when in fact she graduated from an accredited Caribbean medical school, which lots of doctors go to. It’s not a sin—

Edney: Right.

Rovner: —and it’s a perfectly, as I say, accredited medical school. That was basically — but she did fudge it on her resume.

Edney: Yeah.

Rovner: So apparently that was one of the things that got her pulled.

Edney: Right. And the other, kind of, that we’ve seen in recent days, again, is Laura Loomer coming out against her because she thinks she’s not anti-vaccine enough. So what the question I think to maybe be looking into today and after is: Is Casey Means anti-vaccine enough for them? I don’t know exactly the answer to that and whether she’ll make it through as well.

Rovner: Well, we also learned this week that Vinay Prasad, a controversial figure in the covid movement and even before that, has been named to head the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] Center for Biologics and Evaluation Research, making him the nation’s lead vaccine regulator, among other things. Now he does have research bona fides but is a known skeptic of things like accelerated approval of new drugs, and apparently the biotech industry, less than thrilled with this pick, Anna?

Edney: Yeah, they are quite afraid of this pick. You could see it in the stocks for a lot of vaccine companies, for some other companies particularly. He was quite vocal and quite against the covid vaccines during covid and even compared them to the Nazi regime. So we know that there could be a lot of trouble where, already, you know, FDA has said that they’re going to require placebo-controlled trials for new vaccines and imply that any update to a covid vaccine makes it a new vaccine. So this just spells more trouble for getting vaccines to market and quickly to people. He also—you mentioned accelerated approval. This is a way that the FDA uses to try to get promising medicines to people faster. There are issues with it, and people have written about the fact that they rely on what are called surrogate endpoints. So not Did you live longer? but Did your tumor shrink?

And you would think that that would make you live longer, but it actually turns out a lot of times it doesn’t. So you maybe went through a very strong medication and felt more terrible than you might have and didn’t extend your life. So there’s a lot of that discussion, and so that. There are other drugs. Like this Sarepta drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a big one that Vinay Prasad has come out against, saying that should have never been approved, because it was using these kind of surrogate endpoints. So I think biotech’s pretty — thinking they’re going to have a lot tougher road ahead to bring stuff to market.

Rovner: And I should point out that over the very long term, this has been the continuing struggle at FDA. It’s like, do you protect the public but make people wait longer for drugs or do you get the drugs out and make sure that people who have no other treatments available have something available? And it’s been a constant push and pull. It’s not really been partisan. Sometimes you get one side pushing and the other side pushing back. It’s really nothing new. It’s just the sort of latest iteration of this.

Edney: Right. Yeah. This is the pendulum swing, back to the Maybe we need to be slowing it down side. It’s also interesting because there are other discussions from RFK Jr. that, like, We need to be speeding up approvals and Trump wants to speed up approvals. So I don’t know where any of this will actually come down when the rubber meets the road, I guess.

Rovner: Sandhya and Maya, I see you both nodding. Do you want to add something?

Raman: I think this was kind of a theme that I also heard this week in the — we had the Senate Finance hearing for some of the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] nominees, and Jim O’Neill, who’s one of the nominees, that was something that was brought up by Finance ranking member Ron Wyden, that some of his past remarks when he was originally considered to be on the short list for FDA commissioner last Trump administration is that he basically said as long as it’s safe, it should go ahead regardless of efficacy. So those comments were kind of brought back again, and he’s in another hearing now, so that might come up as an issue in HELP [the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions] today.

Rovner: And he’s the nominee for deputy secretary, right? Have to make sure I keep all these things straight. Maya, you wanting to add something?

Goldman: Yeah, I was just going to say, I think there is a divide between these two philosophies on pharmaceuticals, and my sense is that the selection of Prasad is kind of showing that the anti-accelerated-approval side is winning out. But I think Anna is correct that we still don’t know where it’s going to land.

Rovner: Yes, and I will point out that accelerated approval first started during AIDS when there was no treatments and basically people were storming the — literally physically storming — the FDA, demanding access to AIDS drugs, which they did finally get. But that’s where accelerated approval came from. This is not a new fight, and it will continue.

Turning to abortion, the Trump administration surprised a lot of people this week when it continued the Biden administration’s position asking for that case in Texas challenging the abortion pill to be dropped. For those who’ve forgotten, this was a case originally filed by a bunch of Texas medical providers demanding the judge overrule the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone in the year 2000. The Supreme Court ruled the original plaintiff lacked standing to sue, but in the meantime, three states —Missouri, Idaho, and Kansas — have taken their place as plaintiffs. But now the Trump administration points out that those states have no business suing in the Northern District of Texas, which kind of seems true on its face. But we should not mistake this to think that the Trump administration now supports the current approval status of the abortion bill. Right, Sandhya?

Raman: Yeah, I think you’re exactly right. It doesn’t surprise me. If they had allowed these three states, none of which are Texas — they shouldn’t have standing. And if they did allow them to, that would open a whole new can of worms for so many other cases where the other side on so many issues could cherry-pick in the same way. And so I think, I assume, that this will come up in future cases for them and they will continue with the positions they’ve had before. But this was probably in their best interest not to in this specific one.

Rovner: Yeah. There are also those who point out that this could be a way of the administration protecting itself. If it wants to roll back or reimpose restrictions on the abortion pill, it would help prevent blue states from suing to stop that. So it serves a double purpose here, right?

Raman: Yeah. I couldn’t see them doing it another way. And even if you go through the ruling, the language they use, it’s very careful. It’s not dipping into talking fully about abortion. It’s going purely on standing. Yeah.

Rovner: There’s nothing that says, We think the abortion pill is fine the way it is. It clearly does not say that, although they did get the headlines — and I’m sure the president wanted — that makes it look like they’re towing this middle ground on abortion, which they may be but not necessarily in this case.

Well, before we move off of reproductive health, a shoutout here to the incredible work of ProPublica, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for public service this week for its stories on women who died due to abortion bans that prevented them from getting care for their pregnancy complications. Regular listeners of the podcast will remember that we talked about these stories as they came out last year, but I will post another link to them in the show notes today.

OK, moving on. There’s even more drug price news this week, starting with the return of, quote, “most favored nation” drug pricing. Anna, remind us what this is and why it’s controversial.

Edney: Yeah. So the idea of most favored nation, this is something President Trump has brought up before in his first administration, but it creates a basket, essentially, of different prices that nations pay. And we’re going to base ours on the lowest price that is paid for—

Rovner: We’re importing other countries’—

Edney: —prices.

Rovner: —price limits.

Edney: Yeah. Essentially, yes. We can’t import their drugs, but we can import their prices. And so the goal is to just basically piggyback off of whoever is paying the lowest price and to base ours off of that. And clearly the drug industry does not like this and, I think, has faced a number of kind of hits this week where things are looming that could really come after them. So Politico broke that news that Trump is going to sign or expected to sign an executive order that will direct his agencies to look into this most-favored-nation effort. And it feels very much like 2.0, like we were here before. And it didn’t exactly work out, obviously.

Rovner: They sued, didn’t they? The drug industry sued, as I recall.

Edney: Yeah, I think you’re right. Yes.

Goldman: If I’m remembering—

Rovner: But I think they won.

Goldman: If I’m remembering correctly, it was an Administrative Procedure Act lawsuit though, right? So—

Rovner: It was. Yes. It was about a regulation. Yes.

Goldman: —who knows what would happen if they go through a different procedure this time.

Rovner: So the other thing, obviously, that the drug industry is freaked out about right now are tariffs, which have been on again, off again, on again, off again. Where are we with tariffs on — and it’s not just tariffs on drugs being imported. It’s tariffs on drug ingredients being imported, right?

Edney: Yeah. And that’s a particularly rough one because many ingredients are imported, and then some of the drugs are then finished here, just like a car. All the pieces are brought in and then put together in one place. And so this is something the Trump administration has began the process of investigating. And PhRMA [Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America], the trade group for the drug industry, has come out officially, as you would expect, against the tariffs, saying that: This will reduce our ability to do R&D. It will raise the price of drugs that Americans pay, because we’re just going to pass this on to everyone. And so we’re still in this waiting zone of seeing when or exactly how much and all of that for the tariffs for pharma.

Rovner: And yet Americans are paying — already paying — more than they ever have. Maya, you have a story just about that. Tell us.

Goldman: Yeah, there was a really interesting report from an analytics data firm that showed the price that Americans are paying for prescriptions is continuing to climb. Also, the number of prescriptions that Americans are taking is continuing to climb. It certainly will be interesting to see if this administration can be any more successful. That report, I don’t think this made it into the article that I ended up writing, but it did show that the cost of insulin is down. And that’s something that has been a federal policy intervention. We haven’t seen a lot of the effects yet of the Medicare drug price negotiations, but I think there are signs that that could lower the prices that people are paying. So I think it’s interesting to just see the evolution of all of this. It’s very much in flux.

Rovner: A continuing effort. Well, we are now well into the second hundred days of Trump 2.0, and we’re still learning about the cuts to health and health-related programs the administration is making. Just in this week’s rundown are stories about hundreds more people being laid off at the National Cancer Institute, a stop-work order at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases research lab at Fort Detrick, Maryland, that studies Ebola and other deadly infectious diseases, and the layoff of most of the remaining staff at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

A reminder that this is all separate from the discretionary-spending budget request that the administration sent up to lawmakers last week. That document calls for a 26% cut in non-mandatory funding at HHS, meaning just about everything other than Medicare and Medicaid. And it includes a proposed $18 billion cut to the NIH [National Institutes of Health] and elimination of the $4 billion Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps millions of low-income Americans pay their heating and air conditioning bills. Now, this is normally the part of the federal budget that’s deemed dead on arrival. The president sends up his budget request, and Congress says, Yeah, we’re not doing that. But this at least does give us an idea of what direction the administration wants to take at HHS, right? What’s the likelihood of Congress endorsing any of these really huge, deep cuts?

Raman: From both sides—

Rovner: Go ahead, Sandhya.

Raman: It’s not going to happen, and they need 60 votes in the Senate to pass the appropriations bills. I think that when we’re looking in the House in particular, there are a lot of things in what we know from this so-called skinny budget document that they could take up and put in their bill for Labor, HHS, and Education. But I think the Senate’s going to be a different story, just because the Senate Appropriations chair is Susan Collins and she, as soon as this came out, had some pretty sharp words about the big cuts to NIH. They’ve had one in a series of two hearings on biomedical research. Concerned about some of these kinds of things. So I cannot necessarily see that sharp of a cut coming to fruition for NIH, but they might need to make some concessions on some other things.

This is also just a not full document. It has some things and others. I didn’t see any to FDA in there at all. So that was a question mark, even though they had some more information in some of the documents that had leaked kind of earlier on a larger version of this budget request. So I think we’ll see more about how people are feeling next week when we start having Secretary Kennedy testify on some of these. But I would not expect most of this to make it into whatever appropriations law we get.

Goldman: I was just going to say that. You take it seriously but not literally, is what I’ve been hearing from people.

Edney: We don’t have a full picture of what has already been cut. So to go in and then endorse cutting some more, maybe a little bit too early for that, because even at this point they’re still bringing people back that they cut. They’re finding out, Oh, this is actually something that is really important and that we need, so to do even more doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense right now.

Rovner: Yeah, that state of disarray is purposeful, I would guess, and doing a really good job at sort of clouding things up.

Goldman: One note on the cuts. I talked to someone at HHS this week who said as they’re bringing back some of these specialized people, in order to maintain the legality of, what they see as the legality of, the RIF [reduction in force], they need to lay off additional people to keep that number consistent. So I think that is very much in flux still and interesting to watch.

Rovner: Yeah, and I think that’s part of what we were seeing this week is that the groups that got spared are now getting cut because they’ve had to bring back other people. And as I point out, I guess, every week, pretty much all of this is illegal. And as it goes to courts, judges say, You can’t do this. So everything is in flux and will continue.

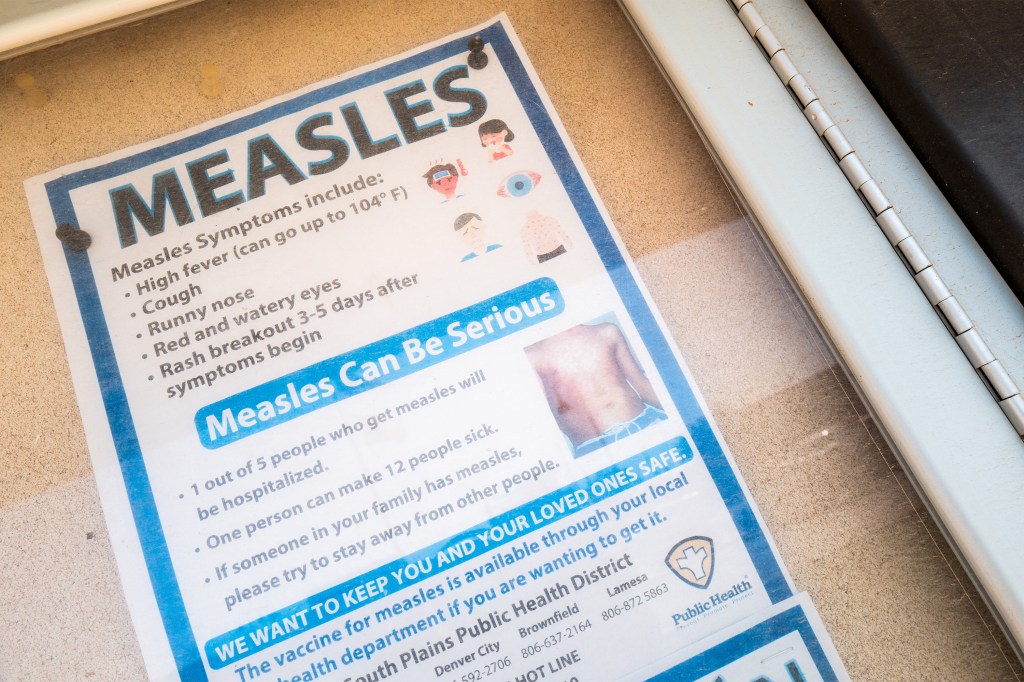

All right, finally this week, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who as of now is scheduled to appear before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee next week to talk about the department’s proposed budget, is asking CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] to develop new guidance for treating measles with drugs and vitamins. This comes a week after he ordered a change in vaccine policy you already mentioned, Anna, so that new vaccines would have to be tested against placebos rather than older versions of the vaccine. These are all exactly the kinds of things that Kennedy promised health committee chairman Bill Cassidy he wouldn’t do. And yet we’ve heard almost nothing from Cassidy about anything the secretary has said or done since he’s been in office. So what do we expect to happen when they come face-to-face with each other in front of the cameras next week, assuming that it happens?

Edney: I’m very curious. I don’t know. Do I expect a senator to take a stand? I don’t necessarily, but this—

Rovner: He hasn’t yet.

Edney: Yeah, he hasn’t yet. But this is maybe about face-saving too for him. So I don’t know.

Rovner: Face-saving for Kennedy or for Cassidy?

Edney: For Cassidy, given he said: I’m going to keep an eye on him. We’re going to talk all the time, and he is not going to do this thing without my input. I’m not sure how Cassidy will approach that. I think it’ll be a really interesting hearing that we’ll all be watching.

Rovner: Yes. And just little announcement, if it does happen, that we are going to do sort of a special Wednesday afternoon after the hearing with some of our KFF Health News colleagues. So we are looking forward to that hearing. All right, that is this week’s news. Now we will play my “Bill of the Month” interview with Lauren Sausser, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am pleased to welcome back to the podcast KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and wrote the latest KFF Health News “Bill of the Month.” Lauren, welcome back.

Lauren Sausser: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Rovner: So this month’s patient got preventive care, which the Affordable Care Act was supposed to incentivize by making it cost-free at the point of service — except it wasn’t. Tell us who the patient is and what kind of care they got.

Sausser: Carmen Aiken is from Chicago. Carmen uses they/them pronouns. And Carmen made an appointment in the summer of 2023 for an annual checkup. This is just like a wellness check that you are very familiar with. You get your vaccines updated. You get your weight checked. You talk to your doctor about your physical activity and your family history. You might get some blood work done. Standard stuff.

Rovner: And how big was the bill?

Sausser: The bill ended up being more than $1,400 when it should, in Carmen’s mind, have been free.

Rovner: Which is a lot.

Sausser: A lot.

Rovner: I assume that there was a complaint to the health plan and the health plan said, Nope, not covered. Why did they say that?

Sausser: It turns out that alongside with some blood work that was preventive, Carmen also had some blood work done to monitor an ongoing prescription. Because that blood test is not considered a standard preventive service, the entire appointment was categorized as diagnostic and not preventive. So all of these services that would’ve been free to them, available at no cost, all of a sudden Carmen became responsible for.

Rovner: So even if the care was diagnostic rather than strictly preventive — obviously debatable — that sounds like a lot of money for a vaccine and some blood test. Why was the bill so high?

Sausser: Part of the reason the bill was so high was because Carmen’s blood work was sent to a hospital for processing, and hospitals, as you know, can charge a lot more for the same services. So under Carmen’s health plan, they were responsible for, I believe it was, 50% of the cost of services performed in an outpatient hospital setting. And that’s what that blood work fell under. So the charges were high.

Rovner: So we’ve talked a lot on the podcast about this fight in Congress to create site-neutral payments. This is a case where that probably would’ve made a big difference.

Sausser: Yeah, it would. And there’s discussion, there’s bipartisan support for it. The idea is that you should not have to pay more for the same services that are delivered at different places. But right now there’s no legislation to protect patients like Carmen from incurring higher charges.

Rovner: So what eventually happened with this bill?

Sausser: Carmen ended up paying it. They put it on a credit card. This was of course after they tried appealing it to their insurance company. Their insurance company decided that they agreed with the provider that these services were diagnostic, not preventive. And so, yeah, Carmen was losing sleep over this and decided ultimately that they were just going to pay it.

Rovner: And at least it was a four-figure bill and not a five-figure bill.

Sausser: Right.

Rovner: What’s the takeaway here? I imagine it is not that you should skip needed preventive/diagnostic care. Some drugs, when you’re on them, they say that you should have blood work done periodically to make sure you’re not having side effects.

Sausser: Right. You should not skip preventive services. And that’s the whole intent behind this in the ACA. It catches stuff early so that it becomes more treatable. I think you have to be really, really careful and specific when you’re making appointments, and about your intention for the appointment, so that you don’t incur charges like this. I think that you can also be really careful about where you get your blood work conducted. A lot of times you’ll see these signs in the doctor’s office like: We use this lab. If this isn’t in-network with you, you need to let us know. Because the charges that you can face really vary depending on where those labs are processed. So you can be really careful about that, too.

Rovner: And adding to all of this, there’s the pending Supreme Court case that could change it, right?

Sausser: Right. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments. It was in April. I think it was on the 21st. And it is a case that originated out in Texas. There is a group of Christian businesses that are challenging the mandate in the ACA that requires health insurers to cover a lot of these preventive services. So obviously we don’t have a decision in the case yet, but we’ll see.

Rovner: We will, and we will cover it on the podcast. Lauren Sausser, thank you so much.

Sausser: Thank you.

Rovner: OK, we’re back. Now it’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s where we each recognize the story we read this week we think you should read, too. Don’t worry if you miss it. We will put the links in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Maya, you were the first to choose this week, so why don’t you go first?

Goldman: My extra credit is from Stat. It’s called “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph. And I just think it’s a really interesting evidence point to the United States’ losses, other countries’ gain. The U.S. has long been the pinnacle of research science, and people flock to this country to do research. And I think we’re already seeing a reversal of that as cuts to NIH funding and other scientific enterprises is reduced.

Rovner: Yep. A lot of stories about this, too. Anna.

Edney: So mine is from a couple of my colleagues that they did earlier this week. “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare.” And I thought it was really interesting because it had brought me back to these cheap, bare-bones plans that people were allowed to start selling that don’t meet any of the Obamacare requirements. And so this guy who used to, in the ’80s and ’90s, wrote for sitcoms — “Coach” or “Night Court,” if anyone goes to watch those on reruns. But he did a series of random things after that and has sort of now landed on selling these junk plans, but doing it in a really weird way that signs people up for a job that they don’t know they’re being signed up for. And I think it’s just, it’s an interesting read because we knew when these things were coming online that this was shady and people weren’t going to get the coverage they needed. And this takes it to an extra level. They’re still around, and they’re still ripping people off.

Rovner: Or as I’d like to subhead this story: Creative people think of creative things.

Edney: “Creative” is a nice word.

Rovner: Sandhya.

Raman: So my pick is “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” and it’s from Anna Claire Vollers at the Louisiana Illuminator. And her story looks at some of the ties between civil rights and health. So 2025 is the 70th anniversary of the bus boycott, the 60th anniversary of Selma-to-Montgomery marches, the Voting Rights Act. And it’s also the 60th anniversary of Medicaid. And she goes into, Medicaid isn’t something you usually consider a civil rights win, but health as a human right was part of the civil rights movement. And I think it’s an interesting piece.

Rovner: It is an interesting piece, and we should point out Medicare was also a huge civil rights, important piece of law because it desegregated all the hospitals in the South. All right, my extra credit this week is a truly infuriating story from NPR by Andrea Hsu. It’s called “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured.” And it’s a situation that if a private employer did it, Congress would be all over them and it would be making huge headlines. These are federal workers who are trying to do the right thing for themselves and their families but who are being jerked around in impossible ways and have no idea not just whether they have jobs but whether they have health insurance, and whether the medical care that they’re getting while this all gets sorted out will be covered. It’s one thing to shrink the federal workforce, but there is some basic human decency for people who haven’t done anything wrong, and a lot of now-former federal workers are not getting it at the moment.

OK, that is this week’s show. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate if you left us a review. That helps other people find us, too. Thanks as always to our editor, Emmarie Huetteman, and our producer, Francis Ying. Also, as always, you can email us your comments or questions, We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org, or you can still find me on X, @jrovner, or on Bluesky, @julierovner. Where are you folks hanging these days? Sandhya?

Raman: I’m on X, @SandhyaWrites, and also on Bluesky, @SandhyaWrites at Bluesky.

Rovner: Anna.

Edney: X and Bluesky, @annaedney.

Rovner: Maya.

Goldman: I am on X, @mayagoldman_. Same on Bluesky and also increasingly on LinkedIn.

Rovner: All right, we’ll be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

5 months 3 weeks ago

Courts, COVID-19, Health Care Costs, Insurance, Medicaid, Multimedia, Pharmaceuticals, Public Health, States, The Health Law, Abortion, Bill Of The Month, Drug Costs, FDA, HHS, Hospitals, KFF Health News' 'What The Health?', NIH, Podcasts, Prescription Drugs, Preventive Services, reproductive health, Surprise Bills, Trump Administration, U.S. Congress, vaccines, Women's Health

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': 100 Days of Health Policy Upheaval

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

Members of Congress are back in Washington this week, and Republicans are facing hard decisions on how to reduce Medicaid spending, even as new polling shows that would be unpopular among their voters.

Meanwhile, with President Donald Trump marking 100 days in office, the Department of Health and Human Services remains in a state of confusion, as programs that were hastily cut are just as hastily reinstated — or not. Even those leading the programs seem unsure about the status of many key health activities.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico Magazine, Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico, and Margot Sanger-Katz of The New York Times.

Panelists

Joanne Kenen

Johns Hopkins University and Politico

Alice Miranda Ollstein

Politico

Margot Sanger-Katz

The New York Times

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- How and what congressional Republicans will propose cutting from federal government spending is still up in the air — one big reason being that the House and Senate have two separate sets of instructions to follow during the budget reconciliation process. The two chambers will need to resolve their differences eventually, and many of the ideas on the table could be politically risky for Republicans.

- GOP lawmakers are reportedly considering imposing sweeping work requirements on nondisabled adults to remain eligible for Medicaid. Only Georgia and Arkansas have tried mandating that some enrollees work, volunteer, go to school, or enroll in job training to qualify for Medicaid. Those states’ experiences showed that work requirements don’t increase employment but are effective at reducing Medicaid enrollment — because many people have trouble proving they qualify and get kicked off their coverage.

- New reporting this week sheds light on the Trump administration’s efforts to go after the accreditation of some medical student and residency programs, part of the White House’s efforts to crack down on diversity and inclusion initiatives. Yet evidence shows that increasing the diversity of medical professionals helps improve health outcomes — and that undermining medical training could further exacerbate provider shortages and worsen the quality of care.

- Trump’s upcoming budget proposal to Congress could shed light on his administration’s budget cuts and workforce reductions within — and spreading out from — federal health agencies. The proposal will be the first written documentation of the Trump White House’s intentions for the federal government.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: KFF Health News’ “As a Diversity Grant Dies, Young Scientists Fear It Will Haunt Their Careers,” by Brett Kelman.

Joanne Kenen: NJ.com’s “Many Nursing Homes Feed Residents on Less Than $10 a Day: ‘That’s Appallingly Low’” and “Inside the ‘Multibillion-Dollar Game’ To Funnel Cash From Nursing Homes to Sister Companies,” by Ted Sherman, Susan K. Livio, and Matthew Miller.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: ProPublica’s “Utah Farmers Signed Up for Federally Funded Therapy. Then the Money Stopped,” by Jessica Schreifels, The Salt Lake Tribune.

Margot Sanger-Katz: CNBC’s “GLP-1s Can Help Employers Lower Medical Costs in 2 Years, New Study Finds,” by Bertha Coombs.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- MedPage Today’s “Trump Order Targets Med School, Residency Accreditors Over ‘Unlawful’ DEI Standards,” by Cheryl Clark.

- Stat’s “Despite Kennedy’s Stated Support, Funding for Women’s Health Initiative Remains in Limbo,” by Elizabeth Cooney.

- CBS News’ “FDA Head Falsely Claims No Scientists Laid Off, as Agency Shutters Food Safety Labs,” by Alexander Tin.

- The New York Times’ “F.D.A. Scientists Are Reinstated at Agency Food Safety Labs,” by Christina Jewett.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: 100 Days of Health Policy Upheaval

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, May 1, at 10:30 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might change by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via videoconference by Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Hello.

Rovner: Margot Sanger-Katz of The New York Times.

Margot Sanger-Katz: Good morning, everybody.

Rovner: And Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico Magazine.

Joanne Kenen: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have a special report on the first 100 days of the second Trump administration and what’s happened in health policy. But first, as usual, this week’s news.

So Congress is back from its spring break and studying for midterms. Oops. I mean it’s getting down to work on President [Donald] Trump’s, quote, “big, beautiful” budget reconciliation bill. For those who may have forgotten, the House Energy and Commerce Committee is tasked with cutting $880 billion over the next decade from programs it oversees. Although the only programs that could really get to that total are Medicare and Medicaid, and Medicare has been declared politically off-limits by President Trump. So what are the options you guys are hearing for how to basically cut Medicaid by 10%, which is effectively what they’re trying to do?

Sanger-Katz: I think it’s a bit of a scramble to decide. My sense is, there’s been for some time a menu of changes that would pull money out of the Medicaid program. There’s also kind of a small menu of other things that the committee has jurisdiction over. And as far as I can tell, all of the various options on that menu are kind of just in a constant rotation of discussion with different members endorsing this one or that one. The president weighs in occasionally or voices from the White House, but I think the committee is waiting on scores from the Congressional Budget Office, so they have to hit this $880 billion number. And so it’s kind of a complicated puzzle to put together the pieces to get to that number and they don’t know what they need. But I also think that they are facing some really difficult politics inside their own caucus in trying to decide what to do and how they can message it in a way that kind of checks everyone’s boxes.

There are some people who have made promises to their constituents that they’re not going to cut Medicaid. There are some people who have said that they only want to do things that would target fraud and abuse. There are some people who have said that they want to make major structural changes to the program. And all of those people are sort of disagreeing about the exact mechanisms.

Rovner: The phrase I keep hearing is that the math doesn’t math.

Sanger-Katz: Yeah. I also think some of them are going to be surprised when the Congressional Budget Office gives them the scores. I think that the leadership has been reassuring a lot of these members, when they voted on these earlier budget bills that were more vague, more theoretical. I think that there were promises that were made to them that, Don’t worry about this. We’re going to solve your problems. This isn’t going to be a huge political headache for you. And I think the reality is is a) The cuts are going to have to be big. That’s what $880 billion means. And b) I think that they are going to be estimated to have pretty big effects on health insurance coverage, because if you’re going to cut $880 billion from Medicaid, that probably means that fewer people are going to be covered. I think some members are going to be surprised by that.

And the other thing is, I think they’re going to start to see in the analyses and hear from local people that some states are going to get hit harder than others. I think there are some states that these members come from where the cuts are going to disproportionately fall. Now we could talk more about the options on the menu. I think some of them will hurt some states more and others will hurt other states more. And I think that is part of the politicking and debate that’s happening as well, where each of these legislators is trying to figure out how they can hit this target, keep their promises, and also protect their own districts to the best of their ability.

Rovner: It seems like one of the things at the top of every Republican’s list that would be quote-unquote “acceptable” would be work requirements. And I heard numbers this week that the CBO is estimating something like more than $200 billion over 10 years in work requirements, which would be pretty strong work requirements. But Alice, you’re our work requirements queen here. We know that the stronger those work requirements are, the more people end up falling off who are still eligible, because most people on Medicaid already work, right?

Ollstein: Yes. The only places in the country that have implemented work requirements for Medicaid have found that it does not increase employment, but it does kick people off the program who should qualify, either because they are working or they have a legitimate reason, they’re a full-time caretaker, they’re a student, they have a disability to not be able to work, and they lose their coverage anyway because they can’t navigate the bureaucracy. And I think what Margot is really getting to is, the fundamental dilemma that Republicans are facing right now as they try to put this together is that the proposals that are most politically palatable to them, like work requirements, won’t get them anywhere near the amount of money they need to cut, that they’ve promised to cut, that they’ve passed a bill pledging to cut in this space. And so that will mean that other things will have to be considered.

And again, I feel like I say this every time, but we really have to be paying very close attention to semantics here. What one person considers a cut when they say the word “cut” is not necessarily what all of us would consider a cut. What some people in power are labeling waste, fraud, and abuse is people getting health care under the law legitimately. They think they shouldn’t, but they do. And so I think we really need to scrutinize the exact language people are using here.

Rovner: There does seem to be kind of a zeroing in on what we call the expansion population, the population that was added to Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which were people who were not the traditional welfare moms and kids and people with disabilities and seniors in nursing homes. These were people who were otherwise low-income but didn’t have health insurance, which is kind of the point. That’s why we say most of these people are already working. You’re not going to live on your Medicaid benefits. There’s no cash involved. The cash goes to the people who provide the actual health care or in some cases the insurers. But that seems to be when — you were talking about semantics — you see Republicans talking about protecting the most vulnerable. That sounds like they really do want to go after this expansion population. But Margot, as you said, a lot of this expansion population is in red states, right?

Sanger-Katz: Yeah. I think there’s another dynamic that’s going on right now that is important to keep track of, which is we’re at the sort of beginning of this process. So both the House and Senate have passed budgets. Those lay out these numbers, and they’ve laid out this very high number. It’s a high threshold for the Energy and Commerce Committee in the House. They have to find this $880 billion. After they do that, the entire House has to vote on the entire reconciliation package, which includes not just these changes to Medicaid but also a series of tax changes, changes to defense and homeland security spending, probably reductions in SNAP [the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] and education funding. Then the whole thing goes to the Senate and the Senate has to do its own version.

And the budget itself is a very weird document. Usually what you see with these budgets is that what the instructions are for the House and the Senate match. In this case, they do not. So the House still has to find these very large Medicaid cuts that I think will be politically problematic for certain House members. But the Senate actually doesn’t. It’s very unclear what the Senate’s plan is and whether they are going to try to go as far. And so I think it creates a difficult dynamic where I think some of these House members may not want to take a hard vote on major budget cuts, that could be politically costly to them, if it’s not even going to become law. And so I think that there’s a lot of kind of meeting of reality that is happening right now, which I think doesn’t mean that they won’t come up with a plan. It doesn’t mean that they won’t pass a plan, and it doesn’t mean that they won’t pass a plan that will affect those budgets of their home states.

But I do think that they are in a little bit of a politically uncomfortable position right now, where they’re being asked to vote for something that is going to be unpopular in some quarters and where they don’t even really know if the Senate is going to hold their hand and go along with it.

Ollstein: Just one point. We talk a lot about red states and blue states, but it’s important to remember that blue states have a lot of districts represented by Republicans, and that’s arguably the reason they even have a House majority. And so if they pass something that really sticks it to New York and California, there’s a lot of Republican House members who might be at risk.

Rovner: Yes. And they’re already making noise. And that’s what I was going to say. The last time Republicans went hard after Medicaid after the expansion was during the effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017, obviously, and we have a brand-new poll out today from KFF, shows that, if anything, Medicaid is even more relevant to Republicans than it was eight years ago. Today’s poll found that more than three-quarters of those polled say they oppose major cuts to Medicaid, including 55% of Republicans and 79% of independents. Those are pretty big numbers. I guess it helps explain why we’re seeing so many Republicans who are looking — there’s so much hand-wringing right now when they’re trying to figure out how to get to these numbers. Go ahead, Joanne.

Kenen: The other thing, it’s not just people who have increasingly, across party lines, grown in their affection for Medicaid, which is paying for all sorts of things. It’s paying for long-term care. It’s paying for almost half the births in this country. It’s paying for postpartum care. It’s paying for kids. It’s paying for the disabled. It is paying for a lot of drug and opioid treatment and substance abuse. It is paying for a lot of things. But in addition to the politics of individuals and families relying on — they call it an entitlement for a reason. People feel entitled to it. But once you give it to them, they don’t want to give it away. And it’s hard for politicians. They don’t want to give it up, and it’s hard for politicians to take it away. But the other thing is it’s also incredibly important to health care providers, specifically hospitals, because nursing homes are not going to get cut the way hospitals are vulnerable.

Rural hospitals, urban hospitals — this is just a, particularly in areas where hospitals are already closing and rural states, it would be devastating to hospitals. You’re beginning to hear them talk more and more and more. Ultimately, I think this is going to come down to three syllables: Donald Trump. We are hearing all sorts of things, right?. He is really good at getting what he wants in the House, even if it’s politically difficult. Someone says, I can’t vote for it, they go back, Speaker [Mike] Johnson goes back in wherever he goes back with them and they come out and vote for it, right? It can take a day, it can take a few hours, but Trump hasn’t lost anything on the floor on the budget so far. We’ve gotten to this point. If Trump decides that he’s going to bite this bullet and go for the $800 [billion], he can probably get it through the House if he really decides that that’s what he wants. Unless they really convince him that it’ll cost the Republicans in the House, and then he has to believe them. He has to think that he really is vulnerable and that the Republicans can lose. And there’s all sorts of questions about what elections are going look like in two years.

But I think that the providers, they’re lobbying in ways that we can see and they’re lobbying in ways that we can’t see. So that’s a part of it. And then the other thing is that there’s a really interesting dynamic with the expansion of states. The states that have not expanded Medicaid tend to be mostly, not all, in the South, Republican states. Their people are not covered. The people who fall in the gap are still not covered. So they don’t have such a dog in this fight. But as we’ve already mentioned, places with a lot of working-class Republicans, the irony is to order, to get states to accept Medicaid expansion in the first place under the ACA, the federal government gave a lot of money — 90%, right? There was more originally. They’re still paying 90%. And that cost the federal government a lot, but states don’t want to give that money up. It’s free dollars.

And another layer of weird dynamics is a lot of the conservative states that did expand Medicaid did so with what they call a trigger. If the payment changes, the Medicaid expansion collapses. It’s gone. So there’s this weird dynamic of the states who were most skeptical of Medicaid expansion, ended up making it safe by putting in those triggers because no one wants to pull or press the trigger.

Sanger-Katz: Can I say one more thing—

Rovner: Yes, go ahead.

Sanger-Katz: —about the state-by-state dynamics? Because I’ve actually been thinking about this a lot and doing a lot of reporting on this. Joanne is a 100% right. There are these states that have these triggers. They are predominantly Republican states. So those are states where, again, you’re going to see a lot of people losing coverage, because the state is just going to automatically pull back on all of the coverage for these working-class people who are getting Medicaid because they have a low income. But that’s not universally the case. I did a story a couple of weeks ago. There are three Republican states that actually have constitutional amendments that they have to cover this population. So even more so than the blue states—

Rovner: We talked about your story, Margot.

Sanger-Katz: Yeah? I love it. I love it. But even more so than the blue states, these are states that are really locked in. Those state governments and those state hospitals, to Joanne’s point, are going to face some really, really tough choices if we see the funding go away. And then another option that’s on this menu — and again we don’t know what they’re going to choose — but one possibility that I think a lot of the kind of right-leaning wonks are really pushing is to get rid of something called provider taxes, Medicaid provider taxes. And we don’t need to get into, fully into the weeds of how these work, because they are sort of complicated. But what I will say is that because of the way that Medicaid is financed and because of the history of how these taxes have proliferated and expanded across the country, there are quite a few Republican-led states that would be disproportionately harmed by that policy.

So I just think all of this is a little messy. I think there’s not an easy way — even setting aside the point that Alice made that of course there are Republican lawmakers from blue states. But even if you’re only concerned about the red states, say you’re only concerned about getting the Senate votes and not the House votes, I still think it’s pretty tricky to come up with one of these policies that’s sort of just taking the money out of states where you don’t need votes.

Rovner: Well, they’re supposed to, the committee is supposed to, start marking up its bill next week. I am dubious as to whether that is actually going to happen on time, but we shall see. Obviously much more on this to come. But I want to move on to news from the Trump administration. Last week we talked about threatening letters sent by the interim U.S. attorney in Washington, D.C., to some major medical journals, including the New England Journal of Medicine. This week we have another story from our friends over at MedPage Today about the administration going after medical student and residency accreditation agencies for their DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] efforts, because both organizations have long had robust programs to require medical schools and residency programs to recruit and retain racial and ethnic minorities who are underrepresented in medicine. Now, this isn’t about being woke. Racial and ethnic representation in the health care workforce is an actual health care issue, right?

Kenen: There’s data. There’s a fair amount of data that shows that this kind of representation, patients having providers that they feel can identify with and understand them and come from a similar background. They’re not always a similar background, but there’s this perception of shared understanding. And there’s a ton of data. Not one or two little studies. There’s a ton of data that it actually improves outcomes. I’m actually working on a piece about this right now, so I’ve just read a bunch of it.

Rovner: I had a feeling you would know this.

Kenen: And it’s been pointed out, there was some research in The Milbank Quarterly, too. And I should disclose that Milbank is one of my funders at Hopkins, but they don’t control what I do journalistically. When the courts ruled against DEA in admissions, DEI in admissions, they were looking at sort of the intake, who comes in. And they really weren’t looking at the data of what happens to health care when the workforce is diverse. So there’s a lot of numbers on this, and they looked at one set of numbers and they didn’t look at another pretty solidly researched for many years, like: What is the impact on patients and what is the impact on American health? So if you’re talking about making America healthy again and you want everybody to be healthy, there’s really a good case to be made for a diverse, a competent, well-trained — we’re not talking about letting people in because they’re a token but getting people in who could become qualified doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, whatever, right? And that data was sort of ignored. The outcomes, the down-the-road impact on health was ignored in that court case.

Rovner: Also, the practical implications of this are kind of terrifying. Yanking accrediting responsibilities from these groups could make a big mess out of training the health care workforce. These groups have decades of experience devising and enforcing guidelines for medical education, much more than just DEI — what you have to teach, what they have to learn, what they have to be competent in. If the administration takes away these organizations’ recognition, it could raise real questions about the uniformity of medical education around the U.S., not to mention deprive lots of programs of lots of federal funding, because programs have to be accredited in order to draw federal funding. This could turn into a really big deal.

Kenen: If they go away, what happens?

Rovner: There would be alternate accrediting bodies.

Kenen: But I have — when I read about the threats on the current accreditation bodies, I did not see, in what I read last night, I did not see: Then what? That blank was not filled in as far as I am aware.

Rovner: I don’t think there is a then what. There are some efforts to stand up alternate accrediting bodies, but I don’t think they exist at the moment. And as I said, these are the bodies that have been doing it for now generations of medical students and medical residents. All right, well we also learned this week that the Government Accountability Office, the GAO is investigating 39 different cases of potentially illegal funding freezes, except the agency’s director told a Senate committee, the administration is not cooperating. I think I’ve said this just about every week since February, but there is a law against the administration refusing to spend money appropriated by Congress. And it feels pretty clear in many of these cases that the administration is violating it.

Why aren’t we hearing more about impoundments and rescissions? The administration says they’re going to send up a rescission request, which is what they are supposed to do when they don’t want to spend money. They have to say: Hey, Congress, we don’t think we should spend this money. Will you vote to let us not spend this money? And yet all we do is talk about all of these cases where the administration is not spending money that’s been appropriated.