KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Alabama’s IVF Ruling Still Making Waves

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

Reverberations from the Alabama Supreme Court’s first-in-the-nation ruling that embryos are legally children continued this week, both in the states and in Washington. As Alabama lawmakers scrambled to find a way to protect in vitro fertilization services without directly denying the “personhood” of embryos, lawmakers in Florida postponed a vote on the state’s own “personhood” law. And in Washington, Republicans worked to find a way to satisfy two factions of their base: those who support IVF and those who believe embryos deserve full legal rights.

Meanwhile, Congress may finally be nearing a funding deal for the fiscal year that began Oct. 1. And while a few bipartisan health bills may catch a ride on the overall spending bill, several other priorities, including an overhaul of the pharmacy benefit manager industry, failed to make the cut.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Rachel Cohrs of Stat, Riley Griffin of Bloomberg News, and Joanne Kenen of Johns Hopkins University’s schools of nursing and public health and Politico Magazine.

Panelists

Rachel Cohrs

Stat News

Riley Griffin

Bloomberg

Joanne Kenen

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- Lawmakers are readying short-term deals to keep the government funded and running for at least a few more weeks, though some health priorities like preparing for a future pandemic and keeping down prescription drug prices may not make the cut.

- After the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision that frozen embryos are people, Republicans find themselves divided over the future of IVF. The emotionally charged debate over the procedure — which many conservatives, including former Vice President Mike Pence, believe should remain available — is causing turmoil for the party. And Democrats will no doubt keep reminding voters about it, highlighting the repercussions of the conservative push into reproductive health care.

- A significant number of physicians in Idaho are leaving the state or the field of reproductive care entirely because of its strict abortion ban. With many hospitals struggling with the cost of labor and delivery services, the ban is only making it harder for women in some areas to get care before, during, and after childbirth — whether they need abortion care or not.

- A major cyberattack targeting the personal information of patients enrolled in a health plan owned by UnitedHealth Group is drawing attention to the heightened risks of consolidation in health care. Meanwhile, the Justice Department is separately investigating UnitedHealth for possible antitrust violations.

- “This Week in Health misinformation”: Panelist Joanne Kenen explains how efforts to prevent wrong information about a new vaccine for RSV have been less than successful.

Also this week, Rovner interviews Greer Donley, an associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, about how a 150-year-old anti-vice law that’s still on the books could be used to ban abortion nationwide.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: ProPublica’s “Their States Banned Abortion. Doctors Now Say They Can’t Give Women Potential Lifesaving Care,” by Kavitha Surana.

Rachel Cohrs: The New York Times’ “$1 Billion Donation Will Provide Free Tuition at a Bronx Medical School,” by Joseph Goldstein.

Joanne Kenen: Axios’ “An Unexpected Finding Suggests Full Moons May Actually Be Tough on Hospitals,” by Tina Reed.

Riley Griffin: Bloomberg News’ “US Seeks to Limit China’s Access to Americans’ Personal Data,” by Riley Griffin and Mackenzie Hawkins.

Also mentioned on this week’s podcast:

- The Washington Post’s “Florida Lawmakers Postpone ‘Fetal Personhood’ Bill After Alabama IVF Ruling,” by Lori Rozsa.

- Stat’s “Congress Punts on PBM Reform Efforts,” by Rachel Cohrs and John Wilkerson.

- Politico Magazine’s “There’s a New Life-Saving Vaccine. Why Won’t People Take It?” by Joanne Kenen.

- Stat’s “Experts Say Scale of Change Cyberattack Shows Risks of Centralized Claims Processing,” by Brittany Trang, Tara Bannow, and Bob Herman.

- The Wall Street Journal’s “U.S. Opens UnitedHealth Antitrust Probe,” by Anna Wilde Mathews and Dave Michaels.

- CNN’s “Opinion: It’s Too Dangerous to Allow This Antiquated Law to Exist Any Longer,” by David S. Cohen, Greer Donley, and Rachel Rebouché.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Alabama’s IVF Ruling Still Making Waves

KFF Health News’ ‘What the Health?’Episode Title: Alabama’s IVF Ruling Still Making WavesEpisode Number: 336Published: Feb. 29, 2024

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, Feb. 29, at 10 a.m. Happy leap day, everyone. As always, news happens fast and things might’ve changed by the time you hear this, so here we go.

We are joined today via video conference by Rachel Cohrs of Stat News.

Rachel Cohrs: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Riley Ray Griffin of Bloomberg News.

Riley Griffin: Hello, hello.

Rovner: And Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins University schools of nursing and public health and Politico Magazine.

Joanne Kenen: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have my interview with University of Pittsburgh law professor Greer Donley about that 150-year-old Comstock Act we’ve talked about so much lately. But first, this week’s news.

So as we tape this morning, the latest in a series of short-term spending bills for the fiscal year that began almost five months ago, is a day and a half away from expiring, and the short-term bill for the rest of the government is 15 days from expiring. And apparently the House and Senate are in the process of preparing yet another pair of short-term bills to keep the government open for another week each, making the new deadlines March 8 and March 22. I should point out that the Food and Drug Administration is included in the first set of spending bills that would expire, and the rest of HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] is in the second batch.

So what are the chances that this time Congress can finish up the spending bills for fiscal 2024? Rachel, I call this Groundhog Day, except February’s about to be over.

Cohrs: Yeah, it’s definitely looking better. I think this is the CR [continuing resolution] where, as I’m thinking about it, the adults are in the room and the negotiations are actually happening. Because we had a couple of fake-outs there, where nobody was really taking it seriously, but I think we are finally at a place where they do have some agreement on some spending bills. The House hopefully will be passing some of them, and I’m optimistic that they’ll get it at least close within that March 8-March 22 time frame to extend us out a few more months until we get to do this all over again in September.

At least right now, which it could change, they do have a couple of weeks, but it’s looking like the main kind of health care provisions that we were looking at are going to be more of an end-of-year conversation than happening this spring.

Rovner: Which is anticipating my next question, which is a bunch of smaller bipartisan bills that were expected to catch a ride on the spending bill train seemed to have been jettisoned because lawmakers couldn’t reach agreement. Although it does look like a handful will make it to the president’s desk in this next round, and its last round, of fiscal spending bills for fiscal 2024.

Let’s start with the bills that are expected to be included when we finally get to these spending bills, presumably in March.

Cohrs: So, from my reporting, it sounds like that there’s going to be an extension of funding for the really truly urgent programs that are expiring. We’re talking community health center funding, funding for some public health programs. It’s funding for safety-net hospitals through Medicaid. Those policies might be extended. There’s a chance that there could be some bump in Medicare payments for doctors. I haven’t seen a final number on that yet, but that’s at least in the conversation for this round.

Again, there’s going to be more cuts at the end of this year. So, I think we’ll be continuing to have this conversation, but those look like they’re in for now. Again, we don’t have final numbers, but that’s kind of what we’re expecting the package to look like.

Kenen: And the opioids is under what you described as public health, right, or is that still up in the air?

Cohrs: I think we’re talking SUPPORT Act; I think that is up in the air, from my understanding. With public health programs talking, like, special diabetes reauthorization — there are a couple more small-ball things, but I think SUPPORT Act, PAHPA [Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act], to my understanding, are still up in the air. We’ll just have to wait for text. That hopefully comes soon.

Rovner: Riley, I see you nodding too. Is that what you’re hearing?

Griffin: Yeah. Questions about PAHPA, the authorizations for pandemic and emergency response activities, have been front of mind for folks for months and months, particularly given the timing, right? We are seeing this expire at a time when we’ve left the biggest health crisis of our generation, and seeing that punted further down the road I think will come as a big disappointment to the world of pandemic preparedness and biodefense, but perhaps not altogether unexpected.

Rovner: So Rachel, I know there were some sort of bigger things that clearly got left on the cutting room floor, like legislation to do something about pharmacy benefit managers and site-neutral payments in Medicare. Those are, at least for the moment, shelved, right?

Cohrs: Yes. That’s from my understanding. Again, I will say now they bought themselves a couple more weeks, so who knows? Sometimes a near-death experience is what it takes to get people moving in this town. But the most recent information I have is that site-neutral payments for administering drugs in physicians’ offices, that has been shelved until the end of the year and then also reforms to how PBMs [pharmacy benefit managers] operate. There’s just a lot of different policies floating around and a lot of different committees and they just didn’t come to the table and hash it out in time. And I think leadership just lost patience with them.

They do see that there’s another bite at the apple at the end of the year. We do have a lot of members retiring, Cathy McMorris Rodgers on the House side, maybe [Sen.] Bernie Sanders. He has not announced he’s running for reelection yet. So I think that’s something to keep in mind for the end of the year. And there also is a big telehealth reauthorization coming up, so I think they view that as a wildly popular policy that’s going to be really expensive and it’s going to be another … give them some more time to just hash out these differences.

Kenen: I would also point out that this annual fight about Medicare doctor payments was something that was supposedly permanently fixed. Julie and I spent, and many other reporters, spent countless hours staking out hallways in Congress about this obscure thing that was called SGR, the sustainable growth rate, but everyone called it the “doc fix.” It was this fight every year that went on and on and on about Medicare rates and then they replaced it and it was supposed to be, “We will never have to deal with this again.”

I decided I would never write another story about it after the best headline I ever wrote, which was, “What’s up, doc fix?” But here we are again. Every single year, there’s a fight about …

Rovner: Although this isn’t the SGR, it’s just …

Kenen: They got rid of SGR, that era was over. But what we’ve learned is that era will probably never be over. Every single year, there will be a lobbying blitz and a fight about Medicare Advantage and about Medicare physician pay. It’s like leap year, but it happens every year instead of every four.

Rovner: Because lobbyists need to get paid too.

All right, well, I want to turn to abortion where the fallout continues from that Alabama Supreme Court ruling earlier this month that found frozen embryos are legally children. Republicans, in particular, are caught in an almost impossible position between portions of their base who genuinely believe that a fertilized egg is a unique new person deserving of full legal rights and protections, and those who oppose abortion but believe that discarding unused embryos as part of the in vitro fertilization process is a morally acceptable way for couples to have babies.

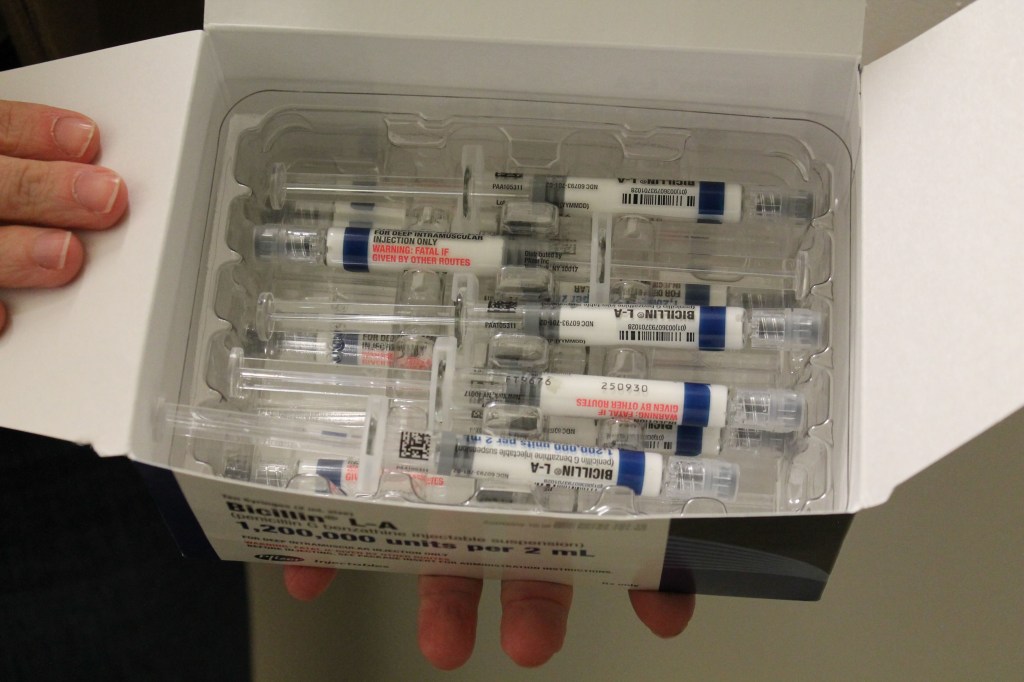

In Alabama, where the ruling has not just stopped IVF clinics from operating in the state, but has also made it impossible for those in the midst of an IVF cycle to take their embryos elsewhere because the companies that would transport them are also worried about liability, the Republican-dominated legislature is scrambling to find a way to allow IVF to resume in the state without directly contradicting the court’s ruling that “personhood” starts at fertilization.

This seems to be quite a tightrope. I mean, Riley, I see you nodding. Can they actually do this? Is there a solution on the table yet?

Griffin: No, I don’t think there’s a solution on the table yet, and there are eight clinics in Alabama that do this work, according to the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]. Three of them have paused IVF treatment across the board. We’ve been in touch with these clinics as days go by as we see some of these developments, and they’re not changing their policies yet. Some of these efforts by Republicans to assure that there won’t be criminal penalties, they’re not reassuring them enough.

So, it certainly is a tightrope for providers and patients. It’s also a tightrope, as you mentioned, Julie, for the Republican Party, which is divided on this matter, and for Republican voters, who are also divided on this matter. But ultimately, this whole conversation comes back to what constitutes a human being? What constitutes a person? And the strategy of giving rights to an embryo allows abortion laws to be even more restrictive across this country.

Rovner: Yeah, I can’t tell you how many stories I’ve written about “When does life begin?” over the last 30 years, because that’s really what this comes down to. Does life begin at fertilization? Does it begin … I mean, doctors, I have learned this over the years, that conception is actually not fertilization. Conception is when basically a fertilized egg implants in a woman’s uterus. That’s when pregnancy begins. So there’s this continuing religious and scientific and ethical and kind of a quagmire that now is front and center again.

Joanne, you wanted to add something?

Kenen: No. I mean, I thought [Sen.] Lindsey Graham had one of the best quotes I’ve seen, which is, “Nobody’s ever been born in a freezer.” So this is a theological question that is turning into a political question. And even the proposed legislation in Alabama, which would give the clinics immunity or a pardon, I mean, pardon means you committed a crime. In this case, a murder, but you were pardoned for it. I mean, I don’t think that’s necessarily … and it’s only good for this was a stopgap that would, if it passes, I believe it would be just till early 2025.

So it might get these clinics open for a while. They may come up with some way of getting families that are in the middle of fertility treatments to be able to complete it, but other states could actually go the way Alabama went. We have no guarantee. There are people pushing for that in some of the more conservative states, so this may spread. The attempt in Congress, in the Senate, to bring up a bill that would address it …

Rovner: We’ll get to that in a second.

Kenen: I mean, Alabama’s a conservative state, but the governor, who was a conservative anti-abortion governor, has said she wants to reopen the clinics and protect them, but they haven’t come up with the formula to do that yet.

Rovner: So speaking of other states, when this decision came down in Alabama, Florida was preparing to pass its own personhood bill, but now that vote has been delayed at the request of the bill’s sponsor. The, I think, initial reaction to the Alabama decision was that it would spur similar action in other states, as you were just saying, Joanne, but is it possible that the opposite will happen, that it will stop action in other states because those who are pushing it are going to see that there’s a huge divide here?

Griffin: That hesitation certainly signals that that’s a possibility. The pause in pushing forward that path in Florida is a real signal that there is going to be more debate within the Republican Party.

One thing I do want to mention is a lot of focus has been on whether clinics in Alabama or otherwise would stop IVF treatment altogether. But I think equally important is how the clinics that are continuing to offer IVF treatment, what changes they’re making. The ones that we’re seeing, are speaking with in Alabama that are continuing to offer IVF, are changing their consent forms. They are fertilizing fewer eggs, they’re freezing eggs, but they’re not fertilizing them because they don’t want to have excess wastage, in their perspective, that could lead them to a place of liability.

So all these things ultimately have ramifications for patients. That is more costly. It means a longer timeline. It also means fewer shots on goal. It means that it is potentially harder for you to get pregnant, at the end of the day. So I want to center the fact that clinics that are continuing to offer IVF are facing real changes here too.

Rovner: We know from Texas that when states try to indemnify, saying, “Well, we won’t prosecute you,” that that’s really not good enough because doctors don’t want to run the chance of ending up in court, having to hire lawyers. I mean, even if they’re unlikely to be convicted and have their licenses taken away, just being charged is hard enough. And I think that’s what’s happening with doctors with some of these abortion exceptions, and that’s what’s happening with these IVF clinics in places where there’s personhood.

Sorry, Joanne. Go ahead.

Kenen: Egg-freezing technology has gotten better than it was just a few years ago, but egg-freezing technology, to the best of my knowledge, egg-freezing technology, though improved, is nowhere near as good as freezing an embryo. Particularly now they can bring embryos out to what they call the blastocyst stage. It’s about five days. They have a better chance of successful implantation.

In addition to the expense of IVF, and it’s expensive and most people don’t have insurance cover[age] for it, it means you’re going through drugs and treatment and all of us have had friends, I think, who’ve gone through it or relatives. It is just an incredibly stressful, emotionally painful process.

Rovner: Well, you’re pumping yourself full of hormones to create more eggs, so yeah.

Kenen: And you’re also trying to get pregnant. If you’re spending $20,000 a cycle or whatever it is, and pumping yourself full of hormones, doing all this, it means that having a child is of utmost importance to you.

And the emotional trauma of this, if you listen to the … we’ve heard interviews in the last few days of women who were about to have a transfer and things like that, the heartbreak is intense, and fertility is not like catching a cold. It’s really stressful and sad, and this is just causing anguish to families trying to have a child, trying to have a first child, trying to have a second child, whatever, or trying to have a child because there’s a health issue and they want to do the pre-implantation genetic testing so that they don’t have another child die. I mean, it’s really complicated and terrible costs on all kinds of costs, physical, emotional, and financial.

Rovner: Yeah, there are lots of layers to this.

Well, meanwhile, this decision has begun to have repercussions here on Capitol Hill. In the Senate, the Democrats are, again, while it’s in the news, trying to force Republicans into taking a stand on this issue by bringing up a bill that would guarantee nationwide access to IVF. This is a bill that they tried to bring up before and was blocked by Republicans. On Wednesday, a half a dozen senators led by Illinois’ Tammy Duckworth, a veteran who used IVF to have her two children, chided Republicans on the floor who failed again to let them bring up the IVF bill. This time, as last time, it was blocked by Republican Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith of Mississippi.

I imagine the Democrats aren’t going to let this go anytime soon though. They certainly indicated that this is not their last attempt at this.

Kenen: No. Why should they? If anyone thought that the politics of abortion were going to subside by November, this has just given it … I don’t even have a word for how much it’s been reinvigorated. This is going to stick in people’s minds, and Republicans are divided on IVF, but there’s no path forward. Democrats are going to be trying again and again, if they can, and they’re going to remind voters of it again and again.

Rovner: And in the Republican House, they’re scrambling to figure out again, as in Alabama, how to demonstrate support for IVF without running afoul of their voters who are fetal personhood supporters.

Just to underline how delicate this all is, the personhood supporting anti-abortion group, Susan B. Anthony [Pro-Life America], put out a statement this week, not just thrashing the Democrats’ bill, which one would expect, but also the work going on by Republicans in Alabama and in the U.S. House for not going far enough. They point out that Louisiana has a law that allows for IVF, but not for the destruction of leftover embryos. Although that means, as Riley was saying before, those embryos have to be stored out of state, which adds to the already high cost of IVF.

It is really hard to imagine how Republicans at both the state and federal level are going to find their way out of this thicket.

Kenen: It’s a reproductive pretzel.

Griffin: It’s a reproductive pretzel where two-thirds of Americans say frozen embryos shouldn’t be considered people. So I mean, there is data to suggest that this isn’t a winning selling point for the Republican Party, and we saw that play out with presidential candidate Donald Trump immediately distancing himself from the Alabama Supreme Court decision. So, what a pretzel it is.

It’s going to be interesting to see how this pans out as the logistical hurdles continue to arise. And some are basic. I mean, I spoke last week with one clinic in Alabama that said that they had had dozens, I think they said 30 to 40, embryos that had been abandoned over decades going back as 2008, and they had tried to reach people by phone, by mail, by email. They had just been left behind. What do you do in that situation? They had been prepared to dispose of those embryos and now they’re sitting on shelves. Is that the answer? Is the only answer to have shelves and shelves of frozen embryos?

Rovner: Yeah, I mean, it is. It is definitely a pretzel.

Kenen: There was a move at one point to allow them to be adopted. I think …

Rovner: It’s still there. It’s still there.

Kenen: Right, but I don’t know what kind of consent you need. I mean, if the situations where someone left the frozen embryo and doesn’t respond or their email, they’ve changed their email or whatever, there may be some kind of way out for this mess that involves the possibility of adopting them at some point down the road, and they may not be biologically viable by that point. But when I was thinking of what are the political outs, what is the exit ramp, I haven’t heard any politicians talk about this yet, but that occurred to me as something that might end up figuring into this.

And the other thing, just to the point as to how deeply divided, I think many listeners know this, but for the handful who don’t, the illustration of how deeply divided even very anti-abortion Republicans are, is [former Vice President] Mike Pence, his family was created through IVF, and he’s clearly, he’s come out this week. I mean, there’s no question that Mike Pence is anti-abortion, there’s not a lot of doubt about that, but he has come forth and endorsed IVF as a life-affirming rather, as a good thing.

Rovner: And I actually went and checked when this all broke because Joanne probably remembers in the mid-2000s when they were talking about stem cell research that President George W. Bush had a big event with what were called “snowflake children,” which were children who were born because they were adopted leftover embryos that someone else basically gestated, and that …

Kenen: But I don’t think they’ll call them “snowflake” anymore.

Rovner: Yeah. Well, that adoption agency is still around and still working and still accepting leftover embryos to be adopted out. That does still exist. I imagine that’s probably of use in Louisiana too, where you’re not allowed to destroy leftover embryos.

Well, meanwhile, we have some new numbers on something else we’ve been talking about since Dobbs [v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization]. Doctors who deliver babies in states with abortion bans are choosing to leave rather than to risk arrest or fines for providing what they consider evidence-based care. In Idaho, according to a new report, 22% of practicing obstetricians stopped practicing or left the state from August 2022 to November 2023. And, at the same time, two hospitals’ obstetric programs in the state closed, while two others report having trouble recruiting enough doctors to keep their doors open.

I would think this is going to particularly impact more sparsely populated states like Idaho, which also, coincidentally or not, are the states that tend to have the strictest abortion bans. I mean, it’s going to be … this seems to be another case where it’s going to be harder, where abortion bans are going to make it harder to have babies.

Cohrs: Yeah. I mean, we’re already seeing a trend of hospital systems being reluctant to keep OB-GYN delivery units open anyway. We’ve seen care deserts. It’s really not a profitable endeavor unless you have a NICU [neonatal intensive care unit] attached. So I think this just really compounds the problems that we’ve been hearing about staffing, about rural health in general, recruiting, and just makes it one step harder for those departments that are really important for women to get the care they need as they’re giving birth, and just making sure that they’re safe and well-staffed for those appointments leading up to and following the birth as well.

Kenen: Right. And at a time we’re supposedly making maternal mortality a national health priority, right? So you can’t really protect women at risk, and, as Rachel said, it’s during childbirth, but it’s for months after. And without proper care, we are not going to be able to either bring down the overall maternal mortality rates nor close the racial disparities.

Griffin: I was just going to say, I highly recommend a story the New Yorker did this past January, “Did an Abortion Ban Cost a Young Texas Woman Her Life?” It’s a view into many of these different themes and will show you a real human story, a tragic one at that, about what these deserts, how they have consequential impact on people’s lives for both mother and baby.

Rovner: Yeah, and we talked about that when it came out. So if you go back, if you scroll back, you’ll find a link to it in the show notes.

I was going to say March is when we get “Match Day,” which is when graduating medical students find out where they’re going to be completing their training. And we saw just sort of the beginnings last year of kind of a dip in graduating medical students who want to become OB-GYNs who are applying to programs in states with abortion bans. I’ll be really curious this year to see whether that was a statistical anomaly or whether really people who want to train to be OB-GYNs don’t want to train in states where they’re really worried about changing laws.

We have to move on. I want to talk about something I’m calling the most under-covered health story of the month, a huge cyberattack on a company called Change Healthcare, which is owned by health industry giant UnitedHealth [Group]. Change processes insurance claims and pharmacy requests for more than 300,000 physicians and 60,000 pharmacies. And as of Wednesday, its systems were still down a week after the attack.

Rachel, I feel like this is a giant flashing red light of what’s at risk with gigantic consolidation in the health care industry. Am I wrong?

Cohrs: You’re right, which is why a couple of my colleagues did cover it as just this important red flag. And there are new SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission] reporting rules as well that require more disclosure around these kind of events. So I think that will …

Rovner: Around the cyberattacks?

Cohrs: Yes, around the cyberattacks, yes. But I think just the idea that, we’ll talk about this later too, but that Change is owned by UnitedHealth and just so much is consolidated that it really does create risks when there are vulnerabilities in these very essential processes. And I think a lot of people just don’t understand how many health care companies, they don’t provide any actual care. They’re just helping with the backroom kind of operations. And when you get these huge conglomerates or services that are bundled together under one umbrella, then it really does show you how a very small company maybe not everyone had heard of before this week could take down operations when you go to your pharmacy, when you go to your doctor’s office.

Rovner: Yeah, and there are doctors who aren’t getting paid. I mean, there’s bills that aren’t getting processed. Everything was done through the mail and it was slow and everybody said, “When we digitize it, it’s all going to be better and it’s all going to happen instantly.” And mostly what it’s done is it’s created all these other companies who are now making money off the health care system, and it’s why health care is a fifth of the U.S. economy.

But anticipating what you were about to say, Rachel, speaking of the giant consolidation in the health industry by UnitedHealth, I am not the only one, we are not the only ones who have noticed. The Wall Street Journal reported this week that the Justice Department has begun an antitrust investigation of said UnitedHealthcare, which provides not only health insurance and claims processing services like those from Change Healthcare, but also through its subsidiary Optum, owns a network of physician groups, one of the largest pharmacy benefit managers, and provides a variety of other health services. Apparently one question investigators are pursuing is whether United favors Optum-owned groups to the detriment of competing doctors and providers.

I think my question here is what took so long? I know that the Justice Department looked at it when United was buying Change Healthcare, but then they said that was OK.

Cohrs: Yeah. I will say I think this is a great piece of reporting here, and these are excellent questions about what happens when the vertical integration gets to this level, which we just really haven’t seen with UnitedHealthcare, where they’re aggressively acquiring provider clinics. I think it was a home health care company that they were trying to buy as well.

So I think it is interesting because now that the acquisitions have happened on some of these, there will be evidence and more material for investigators to look at. It won’t be a theoretical anymore. So I will be interested to see just how this plays out, but it does seem like the questions they’re asking are pretty wide-ranging, certainly related to providers, but also related to an MLR [medical loss ratio]. What if you own a provider that’s charging your insurance company? How does that even work and what are the competitive effects of that for other practices? So I think …

Rovner: And MLRs, for those who are not jargonists, it’s minimum loss ratios [also known as medical loss ratio], and it’s the Affordable Care Act requirement that insurers spend a certain amount of each dollar on actual care rather than overhead and profit and whatnot. So yeah, when you’re both the provider and the insurer, it’s kind of hard to figure out how that’s going.

I am sort of amazed that it’s taken this long because United has been sort of expanding geometrically for the last decade or so.

Kenen: It’s sort of like the term vertical integration, which is the correct term that Rachel used, but as she said that, I sort of had this image of a really tall, skinny, vertical octopus. There’s more and more and more things getting lumped into these big, consolidating, enormous companies that have so much control over so much of health care and concentrated in so few hands now. It’s not just United. I mean, they’re big, but the other big insurers are big too.

Cohrs: Right. I did want to also mention just that we’re kind of seeing this play out in other places too, like Eli Lilly creating telehealth clinics to prescribe their obesity medications. Again, there’s no evidence that they’re connected to this in any way, but I think it is going to be a cautionary tale for other health care companies who are looking into this model and asking themselves, “If UnitedHealthcare can do it, why can’t we do it?” It will be interesting to see how this plays out for the rest of the industry as well.

Rovner: Yeah, when I started covering health policy, I never thought I was going to become a business reporter, but here we are.

Moving on to “This Week in Health Misinformation,” we have Joanne, or rather an interesting, and as it turns out, extremely timely story about vaccines that Joanne wrote for Politico Magazine. Joanne, tell us your thesis here with this story.

Kenen: I wanted to look at how much the public health and clinician community had learned about combating misinformation, sort of a real-life, real-time unfolding before our eyes, which was the rollout of the RSV vaccine.

And I think the two big takeaways, I mean, it’s a fairly … I guess there were sort of three takeaways from that article. One, is they’ve learned stuff but not enough.

Two, is that it’s not that there was this huge campaign against the RSV vaccine, there is misinformation about the RSV vaccine, but basically it just got subsumed into this nonstop, ever-growing anti-vaccine movement that you didn’t have to target RSV. Vaccines is a dirty word for a section of the population.

And the third thing I learned is that the learning about fighting disinformation, the tools we have, you can learn about those tools and deploy those tools, but they don’t work great. There’ve been some studies that have found that what they call debunking or fact-checking, teaching people that what they believe is untrue, that they say, “Ah, that’s not right,” and then a week later they’re back to their original, as little as one week in some studies. One week, you’re back to what you originally thought. So we just don’t know how to do this yet. There are more and more tools, but we are not there.

Rovner: Well, and I say this story is timely because we’re looking at a pretty scary measles outbreak in Florida and a Florida surgeon general who has rejected all established public health advice by telling parents it’s up to them whether to send their exposed-but-unvaccinated children to school rather than keep them home for the full 21 days that measles can take to incubate.

The surgeon general has been publicly taken to task by, among others, Florida’s former surgeon general. I can remember several measles outbreaks over the years, often in less-than-fully-vaccinated communities, but I can’t remember any public health officials so obviously flouting standard public health advice.

Joanne, have you ever seen anything like this?

Kenen: No. It’s like his public stance is like, “Measles, schmeasles.” It’s like a parent has the right to decide whether they’re potentially contagious, goes to school and infects other children, some of whom may be vulnerable and have health problems. It is this complete elevation of medical liberty or medical freedom completely disconnected to the fact that we are connected to one another. We live in communities. We supposedly care about one another. We don’t do a very good job of that, and this is sort of the apotheosis of that.

Rovner: And one of the main reasons that public schools require vaccines is not just for the kids themselves, but for kids who may have younger siblings at home who are not yet fully vaccinated. That’s the whole idea behind herd immunity, is that if enough people are vaccinated then those who are still not fully vaccinated will be protected because it won’t be floating around. And obviously in Florida, measles, which is, according to many doctors, one of the most contagious diseases on the planet, is making a bit of a comeback. So it is sort of, as you point out, kind of the end result of this demonization of all vaccines.

Kenen: And our overall vaccination rate for childhood immunization has dropped and it’s dropped, I’d have to fact-check myself, I think what you need for herd immunity is 95% and it’s …

Rovner: I think it’s over 95.

Kenen: And that we’re down to maybe 93[%]. I mean, this number was in that article that I wrote, but I wrote it a few weeks ago and I may be off by a percentage point, so I want to sort of clarify that nobody should quote me without double-checking that. But basically, we’re not where we need to be and we’re not where we were just a few years ago.

Rovner: Another space we will continue to watch.

Well, that is this week’s news. Now we will play my interview with law professor Greer Donley, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am thrilled to welcome to the podcast, Greer Donley, associate dean for research and faculty development and associate professor of law at the University of Pittsburgh Law School. She’s an expert in legal issues surrounding reproductive health in general and abortion in particular, and someone whose work I have regularly relied on over the past several years, so thank you so much for joining us.

Greer Donley: I’m so happy to be here. Thanks for having me.

Rovner: So I’ve asked you here to talk about how an anti-abortion president could use an 1873 law called the Comstock Act to basically ban abortion nationwide. But first, because it is still so in the news, I have to ask you about the controversy surrounding the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling that frozen embryos for in vitro fertilization are legally children. Do you think this is a one-off, or is this the beginning of states really, fully embracing the idea of personhood from the moment of fertilization?

Donley: Man, I have a lot to say about that. So I’ll start by saying that first of all, this is the logical extension of what people have been saying for a long time about, “If life starts at conception, this is what that means.” So in some sense, this is one of those things where people say, “Believe people when they tell you something.” Folks have been saying forever, “Life starts at conception.” This is a logical outgrowth of that. So in some sense, it’s not particularly surprising.

It’s also worth noting that states have been moving towards personhood for decades, often through these kind of state laws, like wrongful death, which is exactly what happened here. So this is the first case that found that an embryo outside of a uterus was a children for this purpose of wrongful death, but many states had been moving in the direction of finding a fetus or even an embryo that’s within a pregnant person to be a child for the purpose of wrongful death for a while now. And that has always been viewed as the anti-abortion movement towards personhood. In some sense, this is just kind of the logical outgrowth, the logical extension, of the personhood movement and the permission that Dobbs essentially gave to states to go as far as they wanted to on this question.

So whether or not this is going to be the beginning of a new trend is, I think, in my mind, going to be really shaped by public backlash to the Alabama decision, particularly. I think that many folks within the anti-abortion movement, again, they mean what they say. They do believe that this is a life and it should be treated as any other life, but whether or not they are going to perceive this as the ideal political climate in which to push that agenda is another question.

And my personal view is that, given the backlash to the Alabama Supreme Court, you might see folks retreating a little bit from this. I think we’re starting to see a little bit of that, where more moderate people within the Republican Party are going to say, “This is not the moment to go this far,” or maybe even, “I’m not sure I actually support this logical outgrowth of my own opinion,” and so we’re going to have to kind of …

Rovner: “I co-sponsored this bill, but I didn’t realize that’s what it would do.”

Donley: Exactly. Right? So we’re going to, I think, really have to see how people’s views change in response to the backlash.

Rovner: Let us go back to Comstock. Who was this person, Anthony Comstock? What does this law do and why is it still on the books 151 years after it was passed?

Donley: Ugh, yes, OK. So Anthony Comstock, he is what people often call, “The anti-vice crusader.” This law passed in 1873. It’s actually a series of laws, but we often compile them and call them the Comstock Act.

The late 1800s were a moment of change, where many people in this country were for the first time being exposed to the idea that abortion is immoral for religious reasons. Before that for a long time, in the early 1800s, people regularly purchased products to try to what they call, “Bring on the menses,” or menstrual regulation. So it was not uncommon. It was a fairly commonly held view up until late 1800s that the pregnancy was nothing until it was a quickening, there was a quickening where the pregnant person felt movement.

So Comstock was one of the people who was really kind of a part of changing that culture in the late 1800s, and he had the power as the post office inspector of investigating the mail throughout our country. So he was influential not only in helping to pass a law that made it illegal to ship through interstate commerce all sorts of things that he considered immoral, which explicitly included abortion and contraception, but also used vague terms like “anything immoral.” And he was the person that was then in charge of enforcing those laws by actually investigating the mail. His investigations led to pretty horrible outcomes, including many people killing themselves after he started investigating them for a variety of Comstock-related crimes at the time.

So obviously, this law was passed before women had the right to vote, in a completely different time period than we exist today, and it really remained on the books by an accident of history, in my mind.

So in the early 1900s, there was a series of cases. This was the moment where we particularly saw a huge movement towards birth control. So as that movement was going on, you saw a lot of litigation in the courts that were interpreting the Comstock laws related to contraception, finding that it had to be narrowly limited to only unlawful contraception or unlawful abortion. Because the Comstock laws, by its terms, which this should shock everybody who’s hearing me, has literally no exceptions, not even for the life of the pregnant person. And it is so broad that it would ban abortion nationwide from the beginning of a pregnancy without exception. Procedural abortion, pills, everything.

Rovner: And people think of this as the U.S. mail, but it’s not just the U.S. mail. It’s basically any way you move things across state lines, right?

Donley: Right. Because we live in a national economy now, so there’s nothing in medicine that exists in a purely intrastate environment. So every abortion provider in the country is dependent on them and their state mail to get things that they need for procedural abortion and pills.

In the early to mid-1900s, right around the 1930s, there was a series of cases that said this law only applied for unlawful contraception and abortion because they had to read that term into the law. Eventually in the late 1930s, you saw the federal government stop enforcing it completely. And then you had the constitutional cases came out that found a right to contraception and abortion, and so the law was presumed unconstitutional for half a century. No one was repealing it because everyone assumed that it was never going to come back to life. In comes Dobbs, in come the modern anti-abortion movement, and now we are here.

Rovner: Yeah. So how could a President Trump, if he returns to the White House, use this to ban abortion nationwide?

Donley: Yes, because this law was never repealed, and because the case that presumptively made it unconstitutional, Roe v. Wade, and the cases that came after that, are now no longer good law, presumptively the law, like a zombie, comes back to life.

And so the anti-abortion movement is now trying to reinterpret the law, right? We’re talking about such a long period of time and all those 1930s cases, since that time period, you have the rise of what we call textualism, which is a theory of statutory interpretation that really likes to stick to the text. That was something that’s been around for a while, but in modern jurisprudence, that has become increasingly important, and the anti-abortion movement sees, “Well, all these judges are now textualists, and we can say this law is still good. By its clear terms, it bans shipping through interstate commerce anything that could be used for an abortion. Voila. We have our national abortion ban without having to get a single vote in Congress. All we need is a Republican president that will enforce the law as it’s written and on the books today,” and that is their theory.

Rovner: And that’s included, I think, in one of the briefs that was filed today in the abortion pill case, right?

Donley: Absolutely. In that case, that’s a case concerning the regulation of mifepristone, one of the abortion pills, that’s before the Supreme Court this summer. You had parties saying, “The law is clear and it is as broad as it’s written,” essentially.

Rovner: Well, this doesn’t apply to contraception anymore, right?

Donley: Right. So right after the Supreme Court case Griswold [v. Connecticut], which found a constitutional right to contraception, but before Roe, you had the Congress actually repealed the portion of Comstock related to contraception. But again, it was before Roe, so they didn’t repeal the part related to abortion, and then Roe came in and made that part presumptively unconstitutional.

Of course, going back in time, we would say, “You got to repeal that law. You have no idea what the future may be,” but I don’t think people really saw this moment coming. They should have. We should have all been preparing for this more. But, yeah.

Rovner: One of the things that I don’t think I had appreciated until I read the op-ed that you co-wrote, thank you very much, is that there could be a reach-back here. It’s not even just abortions going forward, right?

Donley: Right. So the idea here is that, generally, laws have a statute of limitations, right? So you could potentially have a President Trump come in, say that he’s going to start enforcing this law immediately, and even if the second Jan. 1 comes, people stop shipping anything through interstate commerce, he could still go back and say, “Well, the statute of limitations is five years.” So you go back in time for five years and potentially bring charges against someone.

So one of the important pieces of advocacy that we might have in this moment is to really encourage President Biden, if he were to not win the election, to preemptively essentially pardon anybody for any Comstock-related crimes to make sure that that can’t be used against them. That’s a power he actually has and will be a very important power for him to use in that instance. But it’s quite alarming how Comstock could be used in this period, but also retrospectively.

Rovner: Last question, and I know the answer to this, but I think I need to remind listeners, if Congress doesn’t have to pass anything to implement a nationwide ban, why haven’t previous anti-abortion Republican presidents tried to do this?

Donley: While Roe and [Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v.] Casey were good law, there was no way that they could possibly do that. It would’ve been unconstitutional for them to try to criminalize people for exercising their constitutional right to reproductive health care for abortion. So we’re really in a new moment where essentially the Supreme Court overturned those cases while President Biden was in office, and so the real question is whether a Republican administration could come in and change everything.

Rovner: We shall see. Greer Donley, thank you so much for coming to explain this.

Donley: Thank you for having me.

Rovner: OK, we are back. It’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s when we each recommend a story we read this week we think you should read, too. As always, don’t worry if you miss it. We will post the links on the podcast page at kffhealthnews.org and in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device.

Rachel, you were the first to choose this week. Why don’t you go first?

Cohrs: The article I chose is in The New York Times. The headline is “$1 Billion Donation Will Provide Free Tuition at a Bronx Medical School” by Joseph Goldstein. And it’s about how this 93-year-old widow of an early investor in Berkshire Hathaway has given $1 billion to a medical school in the Bronx to pay for students’ tuition. And I think her idea behind it is that it will open up the pool of students who might be able to go to medical school. I imagine applications might increase to this school as well. And she was a professor at the school during her career as well.

To me, it’s not a scalable solution necessarily for the cost of medical education, but I think it does highlight how broke everything is. When we’re talking about Medicare payment to doctors, I think one of the arguments they always use is doctors have debt and there’s inflation and costs have gone up so much, and I think the cost of education in this country certainly is one factor in that, that it’s really hard to address from a simply health care policy standpoint.

So I think not necessarily a scalable solution, but will definitely make a difference in a lot of students’ lives and just give them more freedom to practice in the specialty that they might want to, which we all know we need more primary care doctors and doctors in a variety of different settings. So I think it’s a rare piece of good news.

Rovner: Yeah, it might not be scalable, but it’s not the first, which is kind of … I remember, in fact, NYU is now having a no-tuition medical school. UCLA, although I think UCLA is only for students who can demonstrate financial need. But in doing those earlier stories, and I have not updated this, at the time, which is a couple of years ago, the average medical student debt graduating is over $250,000. So you can see why they feel like they need to be in more lucrative specialties because they’re going to be paying their student loans back until they’re in their 40s, most of them. This is clearly a step in that direction.

Riley, why don’t you go next?

Griffin: Yeah. I wanted to share a story that I’ve been fairly obsessed with over the last month. It’s one of my own. It’s “US Seeks to Limit China’s Access to Americans’ Personal Data.” This week, the Biden administration announced that it is issuing, or has at this point issued, an executive order to secure Americans’ sensitive personal data, and we broke this story about a month ago.

Why it is so interesting to the health world is, one of the key parts that was a motivating factor in putting together this executive order, is DNA, genomic data. The U.S., the National Security Council, our national security apparatus is really concerned about what China and other foreign adversaries are doing with our genetic information. And we can get more into that in the story itself, but it is fascinating, and now we’re seeing real action to regulate and protect and ensure that that bulk data doesn’t get into the hands of people who want to use it for blackmail and espionage.

Rovner: Yeah, it was super scary, I will say. Joanne?

Kenen: I couldn’t resist this one. It’s in Axios. It’s by Tina Reed, and the headline is “An Unexpected Finding Suggests Full Moons May Actually Be Tough on Hospitals.” Caveat, before I go on, there is research out there that proves what I’m about to say is wrong.

But anyway, a company that makes panic buttons, so a hospital security company that one of the things they do is provide panic buttons, they did a study of how and when these panic buttons are used, and they found they go up during full moons. And they also found that other things rise during full moons. GI [gastro-intestinal] disorders go up, ambulance rides connected to motor vehicle accidents go up, and psychiatric admissions go up. So maybe that research that I cited at the beginning saying this is hogwash needs to be reevaluated in some subcategories.

Rovner: There’s always new things to find out in science.

My extra credit this week is from ProPublica. It’s called “Their States Banned Abortion. Doctors Now Say They Can’t Give Women Potential Lifesaving Care,” by Kavitha Surana. It’s another in a series of stories we’ve seen about women with serious pregnancy complications that are not immediately life-threatening, but who nevertheless can’t get care that their doctors think they need.

This story, however, is written from the point of view of the doctors, specifically members of an abortion committee at Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville who are dealing with the Tennessee ban that’s one of the strictest in the nation. It’s really putting doctors in an almost impossible position in some cases, feeling that they can’t even tell patients what the risks are of continuing their pregnancies for fear of violating that Tennessee law. It’s a whole new window into this story that we keep hearing about and a really good read.

OK. That is our show. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate it if you left us a review. That helps other people find us too. Special thanks as always to our very patient technical guru, Francis Ying, and our editor, Emmarie Huetteman.

As always, you can email us your comments or questions. We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org, or you can still find me hanging around at Twitter, @jrovner, or @julierovner at Bluesky and @julie.rovner at Threads.

Joanne, where are you hanging these days?

Kenen: Mostly at Threads, @joannekenen1. I still occasionally use X, and that’s @JoanneKenen.

Rovner: Riley, where can we find you on social media?

Griffin: You can find me at X @rileyraygriffin.

Rovner: And Rachel?

Cohrs: I’m at X @rachelcohrs and on LinkedIn more these days, so feel free to follow me there.

Rovner: There you go. We’ll be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 8 months ago

Courts, Multimedia, States, Abortion, Alabama, Florida, Health IT, Idaho, KFF Health News' 'What The Health?', Misinformation, Podcasts, U.S. Congress, Women's Health

Opinion: A new Louisiana capital-punishment bill would fundamentally alter physician licensing

After the recent nitrogen gas execution in Alabama of Kenneth Smith, state Attorney General Steve Marshall said that nitrogen gas “was intended to be — and has now proved to be — an effective and humane method of execution.”

After the recent nitrogen gas execution in Alabama of Kenneth Smith, state Attorney General Steve Marshall said that nitrogen gas “was intended to be — and has now proved to be — an effective and humane method of execution.”

It is hard to imagine a statement so obviously disconnected from facts. Eyewitness accounts described Smith’s death as a harrowing experience of dry heaving, thrashing, straining against leather straps, seizures, and terror. It took about a half-hour for Smith to die, although the state had previously predicted it would be over in minutes.

1 year 8 months ago

First Opinion, ethics, physicians, States

Pregnancy Care Was Always Lacking in Jails. It Could Get Worse.

It was about midnight in June 2022 when police officers showed up at Angela Collier’s door and told her that someone anonymously requested a welfare check because they thought she might have had a miscarriage.

Standing in front of the concrete steps of her home in Midway, Texas, Collier, initially barefoot and wearing a baggy gray T-shirt, told officers she planned to see a doctor in the morning because she had been bleeding.

Police body camera footage obtained by KFF Health News through an open records request shows that the officers then told Collier — who was 29 at the time and enrolled in online classes to study psychology — to turn around.

Instead of taking her to get medical care, they handcuffed and arrested her because she had outstanding warrants in a neighboring county for failing to appear in court to face misdemeanor drug charges three weeks earlier. She had missed that court date, medical records show, because she was at a hospital receiving treatment for pregnancy complications.

Despite her symptoms and being about 13 weeks pregnant, Collier spent the next day and a half in the Walker County Jail, about 80 miles north of Houston. She said her bleeding worsened there and she begged repeatedly for medical attention that she didn’t receive, according to a formal complaint she filed with the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.

“There wasn’t anything I could do,” she said, but “just lay there and be scared and not know what was going to happen.”

Collier’s experience highlights the limited oversight and absence of federal standards for reproductive care for pregnant women in the criminal justice system. Incarcerated people have a constitutional right to health care, yet only a half-dozen states have passed laws guaranteeing access to prenatal or postpartum medical care for people in custody, according to a review of reproductive health care legislation for incarcerated people by a research group at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. And now abortion restrictions might be putting care further out of reach.

Collier’s arrest was “shocking and disturbing” because officers “blithely” took her to jail despite her miscarriage concerns, said Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson for the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit organization that studies incarceration. Bertram reviewed the body cam footage and Collier’s complaint.

“Police arrest people who are in medical emergencies all the time,” she said. “And they do that regardless of the fact that the jail is often not equipped to care for those people in the way an emergency room might be.”

After a decline during the first year of the pandemic, the number of women in U.S. jails is once again rising, hitting nearly 93,000 in June 2022, a 33% increase over 2020, according to the Department of Justice. Tens of thousands of pregnant women enter U.S. jails each year, according to estimates by Carolyn Sufrin, an associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, who researches pregnancy care in jails and prisons.

The health care needs of incarcerated women have “always been an afterthought,” said Dana Sussman, deputy executive director at Pregnancy Justice, an organization that defends women who have been charged with crimes related to their pregnancy, such as substance use. For example, about half of states don’t provide free menstrual products in jails and prisons. “And then the needs of pregnant women are an afterthought beyond that,” Sussman said.

Researchers and advocates worry that confusion over recent abortion restrictions may further complicate the situation. A nurse cited Texas’ abortion laws as one reason Collier didn’t need care, according to her statement to the standards commission.

Texas law allows treatment of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancies, a life-threatening condition in which a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus. However, different interpretations of the law can create confusion.

A nurse told Collier that “hospitals no longer did dilation and curettage,” Collier told the commission. “Since I wasn’t hemorrhaging to the point of completely soaking my pants, there wasn’t anything that could be done for me,” she said.

Collier testified that she saw a nurse only once during her stay in jail, even after she repeatedly asked jail staffers for help. The nurse checked her temperature and blood pressure and told her to put in a formal request for Tylenol. Collier said she completed her miscarriage shortly after being released.

Collier’s case is a “canary in a coal mine” for what is happening in jails; abortion restrictions are “going to have a huge ripple effect on a system already unequipped to handle obstetric emergencies,” Sufrin said.

‘There Are No Consequences’

Jail and prison health policies vary widely around the country and often fall far short of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for reproductive health care for incarcerated people. ACOG and other groups recommend that incarcerated women have access to unscheduled or emergency obstetric visits on a 24-hour basis and that on-site health care providers should be better trained to recognize pregnancy problems.

In Alabama, where women have been jailed for substance use during pregnancy, the state offers pregnancy tests in jail. But it doesn’t guarantee a minimum standard of prenatal care, such as access to extra food and medical visits, according to Johns Hopkins’ review.

Policies for pregnant women at federal facilities also don’t align with national standards for nutrition, safe housing, and access to medical care, according to a 2021 report from the Government Accountability Office.

Even when laws exist to ensure that incarcerated pregnant women have access to care, the language is often vague, leaving discretion to jail personnel.

Since 2020, Tennessee law has required that jails and prisons provide pregnant women “regular prenatal and postpartum care, as necessary.” But last August a woman gave birth in a jail cell after seeking medical attention for more than an hour, according to the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office.

Pregnancy complications can quickly escalate into life-threatening situations, requiring more timely and specialized care than jails can often provide, said Sufrin. And when jails fail to comply with laws on the books, little oversight or enforcement may exist.

In Louisiana, many jails didn’t consistently follow laws that aimed to improve access to reproductive health care, such as providing free menstrual items, according to a May 2023 report commissioned by state lawmakers. The report also said jails weren’t transparent about whether they followed other laws, such as prohibiting the use of solitary confinement for pregnant women.

Krishnaveni Gundu, as co-founder of the Texas Jail Project, which advocates for people held in county jails, has lobbied for more than a decade to strengthen state protections for pregnant incarcerated people.

In 2019, Texas became one of the few states to require that jails’ health policies include obstetrical and gynecological care. The law requires jails to promptly transport a pregnant person in labor to a hospital, and additional regulations mandate access to medical and mental health care for miscarriages and other pregnancy complications.

But Gundu said lack of oversight and meaningful enforcement mechanisms, along with “apathy” among jail employees, have undermined regulatory protections.

“All those reforms feel futile,” said Gundu, who helped Collier prepare for her testimony. “There are no consequences.”

Before her arrest, Collier had been to the hospital twice that month experiencing pregnancy complications, including a bladder infection, her medical records show. Yet the commission found that Walker County Jail didn’t violate minimum standards. The commission did not consider the police body cam footage or Collier’s personal medical records, which support her assertions of pregnancy complications, according to investigation documents obtained by KFF Health News via an open records request.

In making its determination, the commission relied mainly on the jail’s medical records, which note that Collier asked for medical attention for a miscarriage once, in the morning on the day she was released, and refused Tylenol.

“Your complaint of no medical care is unfounded,” the commission concluded, “and no further action will be taken.”

Collier’s miscarriage had ended before she entered the jail, argued Lt. Keith DeHart, jail lieutenant for the Walker County Sheriff’s Office. “I believe there was some misunderstanding,” he said.

Brandon Wood, executive director of the commission, wouldn’t comment on Collier’s case but defends the group’s investigation as thorough. Jails “have a duty to ensure that those records are accurate and truthful,” he said. And most Texas jails are complying with heightened standards, he said.

Bertram disagrees, saying the fact that care was denied to someone who was begging for it speaks volumes. “That should tell you something about what these standards are worth,” she said.

Last year, Chiree Harley spent six weeks in a Comal County, Texas, jail shortly after discovering she was pregnant and before she could get prenatal care, she said.

I was “thinking that I was going to be well taken care of,” said Harley, 37, who also struggled with substance use.

Jail officials put her in the infirmary, Harley said, but she saw only a jail doctor and never visited an OB-GYN, even though she had previous pregnancy complications including losing multiple pregnancies at around 21 weeks. This time she had no idea how far along she was.

She said that she started leaking amniotic fluid and having contractions on Nov. 1, but that jail officials waited nearly two days to take her to a hospital. Harley said officers forced her to sign papers releasing her from jail custody while she was having contractions in the hospital. Harley delivered at 23 weeks; the baby boy died less than a day later in her arms.

The whole experience was “very scary,” Harley said. “Afterwards we were all very, very devastated.”

Comal County declined to send Harley’s medical and other records in response to an open records request. Michael Shaunessy, a partner at McGinnis Lochridge who represents Comal County, said in a statement that, “at all times, the Comal County Jail provided Chiree Harley with all appropriate and necessary medical treatment for her and her unborn child.” He did not respond to questions about whether Harley was provided specialized obstetric care.

‘I Trusted Those People’

In states like Idaho, Mississippi, and Louisiana that installed near-total abortion bans after the Supreme Court eliminated the constitutional right to abortion in 2022, some patients might have to wait until no fetal cardiac activity is detected before they can get care, said Kari White, the executive and scientific director of Resound Research for Reproductive Health.

White co-authored a recent study that documented 50 cases in which pregnancy care deviated from the standard because of abortion restrictions even outside of jails and prisons. Health care providers who worry about running afoul of strict laws might tell patients to go home and wait until their situations worsen.

“Obviously, it’s much trickier for people who are in jail or in prison, because they are not going to necessarily be able to leave again,” she said.

Advocates argue that boosting oversight and standards is a start, but that states need to find other ways to manage pregnant women who get caught in the justice system.

For many pregnant people, even a short stay in jail can cause lasting trauma and interrupt crucial prenatal care.

Collier remembers being in “disbelief” when she was first arrested but said she was not “distraught.”

“I figured I would be taken care of, that nothing bad was gonna happen to me,” she said. As it became clear that she wouldn’t get care, she grew distressed.

After her miscarriage, Collier saw a mental health specialist and started medication to treat depression. She hasn’t returned to her studies, she said.

“I trusted those people,” Collier said about the jail staff. “The whole experience really messed my head up.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

1 year 8 months ago

States, Alabama, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Pregnancy, Prison Health Care, Tennessee, texas, Women's Health

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Alabama Court Rules Embryos Are Children. What Now?

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

The Alabama Supreme Court’s groundbreaking ruling last week that frozen embryos have legal rights as people has touched off a national debate about the potential fallout of the “personhood” movement. Already the University of Alabama-Birmingham has paused its in vitro fertilization program while it determines the ongoing legality of a process that has become increasingly common for those wishing to start a family.

Meanwhile, former President Donald Trump is reportedly leaning toward endorsing a national, 16-week abortion ban. At the same time, former aides are planning a long agenda of reproductive health restrictions should Trump win a second term.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Lauren Weber of The Washington Post, Rachana Pradhan of KFF Health News, and Victoria Knight of Axios.

Panelists

Victoria Knight

Axios

Rachana Pradhan

KFF Health News

Lauren Weber

The Washington Post

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- The Alabama Supreme Court’s decision on embryonic personhood could have wide-ranging implications beyond reproductive health care, with potential implications for tax deductions, child support payments, criminal law, and much more.

- Donald Trump is considering a national abortion ban at 16 weeks of gestation, according to recent reports. It is unclear whether such a ban would go far enough to please his conservative supporters, but it would be far enough to give Democrats ammunition to campaign on it. And some are looking into using a 19th-century anti-smut law, the Comstock Act, to implement a national ban under a new Trump presidency — no action from Congress necessary.

- New reporting from KFF Health News draws on many interviews with clinicians at Catholic hospitals about how the Roman Catholic Church’s directives dictate the care they may offer patients, especially in reproductive health. It also draws attention to the vast number of religiously affiliated hospitals and the fact that, for many women, a Catholic hospital may be their only option.

- Questions about President Joe Biden’s cognitive health are drawing attention to ageism in politics — as well as in American life, with fewer people taking precautions against the covid-19 virus even as it remains a serious threat to vulnerable people, especially the elderly. The mental fitness of the nation’s leaders is a valid, relevant question for many voters, though the questions are also fueled by frustration with a political system in which many offices are held by older people who have been around a long time.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: Stat’s “New CMS Rules Will Throttle Access Researchers Need to Medicare, Medicaid Data,” by Rachel M. Werner.

Lauren Weber: The Washington Post’s “They Take Kratom to Ease Pain or Anxiety. Sometimes, Death Follows,” by David Ovalle.

Rachana Pradhan: Politico’s “Red States Hopeful for a 2nd Trump Term Prepare to Curtail Medicaid,” by Megan Messerly.

Victoria Knight: ProPublica’s “The Year After a Denied Abortion,” by Stacy Kranitz and Kavitha Surana.

Also mentioned on this week’s podcast:

- The New York Times’ “Trump Privately Expresses Support for a 16-Week Abortion Ban,” by Maggie Haberman, Jonathan Swan, and Lisa Lerer.

- The New York Times’ “Trump Allies Plan New Sweeping Abortion Restrictions,” by Lisa Lerer and Elizabeth Dias.

- Politico’s “Trump Allies Prepare to Infuse ‘Christian Nationalism’ in Second Administration,” by Alexander Ward and Heidi Przybyla.

- KFF Health News’ “The Powerful Constraints on Medical Care in Catholic Hospitals Across America,” by Rachana Pradhan and Hannah Recht.

- The Washington Post’s “Tax Records Reveal the Lucrative World of Covid Misinformation,” by Lauren Weber.

- KFF Health News’ “Do We Simply Not Care About Old People?” by Judith Graham.

- Stat’s “A Neuropsychologist Clarifies Science on Aging and Memory in Wake of Biden Special Counsel Report,” by Annalisa Merelli.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Alabama Court Rules Embryos Are Children. What Now?

KFF Health News’ ‘What the Health?’Episode Title: Alabama Court Rules Embryos Are Children. What Now?Episode Number: 335Published: Feb. 22,2024

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello, and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, Feb. 22, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast, and things might have changed by the time you hear this, so here we go. We are joined today via video conference by Lauren Weber of The Washington Post.

Lauren Weber: Hello, hello.

Rovner: Victoria Knight of Axios.

Victoria Knight: Hello, everyone.

Rovner: And my KFF Health News colleague Rachana Pradhan.

Rachana Pradhan: Hi, there. Good to be back.

Rovner: Congress is out this week, but there is still tons of news, so we will get right to it. We’re going to start with abortion because there is lots of news there. The biggest is out of Alabama, where the state Supreme Court ruled last week that frozen embryos created for IVF [in vitro fertilization] are legally children and that those who destroy them can be held liable. In fact, the justices called the embryos “extrauterine children,” which, in covering this issue for 40 years, I never knew was a thing. There are lots of layers to this, but let’s start with the immediate, what it could mean to those seeking to get pregnant using IVF. We’ve already heard that the University of Alabama’s IVF clinic has ceased operations until they can figure out what this means.

Pradhan: I think that that is the immediate fallout right now. We’ve seen Alabama’s arguably flagship university saying that they are going to halt. And I believe some of the coverage that I saw, there was even a woman who was about to start a cycle or was literally about to have embryos implanted and had to encounter that extremely jarring development. Beyond the immediate, and of course, Julie, I’m sure we’ll talk about this, a bit about the personhood movement and fetal rights movement in general, but a lot of the country might say, “Oh, well, it’s Alabama. It’s only Alabama.” But as we know it, it really just takes one state, it seems like these days, to open the floodgates for things that might actually take hold much more broadly across the country. So that’s what I’m …