Republicans Aim To Punish States That Insure Unauthorized Immigrants

President Donald Trump’s signature budget legislation would punish 14 states that offer health coverage to people in the U.S. without authorization.

The states, most of them Democratic-led, provide insurance to some low-income immigrants — often children — regardless of their legal status. Advocates argue the policy is both humane and ultimately cost-saving.

President Donald Trump’s signature budget legislation would punish 14 states that offer health coverage to people in the U.S. without authorization.

The states, most of them Democratic-led, provide insurance to some low-income immigrants — often children — regardless of their legal status. Advocates argue the policy is both humane and ultimately cost-saving.

But the federal legislation, which Republicans have titled the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” would slash federal Medicaid reimbursements to those states by billions of dollars a year in total unless they roll back the benefits.

The bill narrowly passed the House on Thursday and next moves to the Senate. While enacting much of Trump’s domestic agenda, including big tax cuts largely benefiting wealthier Americans, the legislation also makes substantial spending cuts to Medicaid that congressional budget scorekeepers say will leave millions of low-income people without health insurance.

The cuts, if approved by the Senate, would pose a tricky political and economic hurdle for the states and Washington, D.C., which use their own funds to provide health insurance to some people in the U.S. without authorization.

Those states would see their federal reimbursement for people covered under the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion cut by 10 percentage points. The cuts would cost California, the state with the most to lose, as much as $3 billion a year, according to an analysis by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Together, the 15 affected places cover about 1.9 million immigrants without legal status, according to KFF. The penalty might also apply to other states that cover lawfully residing immigrants, KFF says.

Two of the states — Utah and Illinois — have “trigger” laws that call for their Medicaid expansions to terminate if the feds reduce their funding match. That means unless those states either repeal their trigger laws or stop covering people without legal immigration status, many more low-income Americans could be left uninsured.

The remaining states and Washington, D.C., would have to come up with millions or billions more dollars every year, starting in the 2027 fiscal year, to make up for reductions in their federal Medicaid reimbursements, if they keep covering people in the U.S. without authorization.

Behind California, New York stands to lose the most federal funding — about $1.6 billion annually, according to KFF.

California state Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat who chairs the Senate budget committee, said Trump’s legislation has sown chaos as state legislators work to pass their own budget by June 15.

“We need to stand our ground,” he said. “California has made a decision that we want universal health care and that we are going to ensure that everyone has access to health care, and that we’re not going to have millions of undocumented people getting their primary care in emergency rooms.”

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, said in a statement that Trump’s bill would devastate health care in his state.

“Millions will lose coverage, hospitals will close, and safety nets could collapse under the weight,” Newsom said.

In his May 14 budget proposal, Newsom called on lawmakers to cut some benefits for immigrants without legal status, citing ballooning costs in the state’s Medicaid program. If Congress cuts Medicaid expansion funding, the state would be in no position to backfill, the governor said.

Newsom questioned whether Congress has the authority to penalize states for how they spend their own money and said his state would consider challenging the move in court.

Utah state Rep. Jim Dunnigan, a Republican who helped spearhead a bill to cover children in his state regardless of their immigration status, said Utah needs to maintain its Medicaid expansion that began in 2020.

“We cannot afford, monetary-wise or policy-wise, to see our federal expansion funding cut,” he said. Dunnigan wouldn’t say whether he thinks the state should end its immigrant coverage if the Republican penalty provision becomes law.

Utah’s program covers about 2,000 children, the maximum allowed under its law. Adult immigrants without legal status are not eligible. Utah’s Medicaid expansion covers about 75,000 adults, who must be citizens or lawfully present immigrants.

Matt Slonaker, executive director of the Utah Health Policy Project, a consumer advocacy organization, said the federal House bill leaves the state in a difficult position.

“There are no great alternatives, politically,” he said. “It’s a prisoner’s dilemma — a move in either direction does not make much sense.”

Slonaker said one likely scenario is that state lawmakers eliminate their trigger law then find a way to make up the loss of federal expansion funding.

Utah has funded its share of the cost of Medicaid expansion with sales and hospital taxes.

“This is a very hard political decision that Congress would put the state of Utah in,” Slonaker said.

In Illinois, the GOP penalty would have even larger consequences. That’s because it could lead to 770,000 adults’ losing the health coverage they gained under the state’s Medicaid expansion.

Stephanie Altman, director of health care justice at the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, a Chicago-based advocacy group, said it’s possible her Democratic-led state would end its trigger law before allowing its Medicaid expansion to terminate. She said the state might also sidestep the penalty by asking counties to fund coverage for immigrants. “It would be a hard situation, obviously,” she said.

Altman said the House bill appeared written to penalize Democratic-controlled states because they more commonly provide immigrants coverage without regard for their legal status.

She said the provision shows Republicans’ “hostility against immigrants” and that “they do not want them coming here and receiving public coverage.”

U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson said this month that state programs that provide public coverage to people regardless of immigration status serve as “an open doormat,” inviting more people to cross the border without authorization. He said efforts to end such programs have support in public polling.

A Reuters-Ipsos poll conducted May 16-18 found that 47% of Americans approve of Trump’s immigration policies and 45% disapprove. The poll found that Trump’s overall approval rating has sunk 5 percentage points since he returned to office in January, to 42%, with 52% of Americans disapproving of his performance.

The Affordable Care Act, widely known as Obamacare, enabled states to expand Medicaid to adults with incomes of up to 138% of the federal poverty level, or $21,597 for an individual this year. Forty states and Washington, D.C., expanded, helping reduce the national uninsured rate to a historic low.

The federal government now pays 90% of the costs for people added to Medicaid under the Obamacare expansion.

In states that cover health care for immigrants in the U.S. without authorization, the Republican bill would reduce the federal government’s contribution from 90% to 80% of the cost of coverage for anyone added to Medicaid under the ACA expansion.

By law, federal Medicaid funds cannot be used to cover people who are in the country without authorization, except for pregnancy and emergency services.

The other states that use their own money to cover people regardless of immigration status are Colorado, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington, according to KFF.

Ryan Long, director of congressional relations at Paragon Health Institute, an influential conservative policy group, said that even if they use their own money for immigrant coverage, states still depend on federal funds to “support systems that facilitate enrollment of illegal aliens.”

Long said the concern that states with trigger laws could see their Medicaid expansion end is a “red herring” because states have the option to remove their triggers, as Michigan did in 2023.

The penalty for covering people in the country without authorization is one of several ways the House bill cuts federal Medicaid spending.

The legislation would shift more Medicaid costs to states by requiring them to verify whether adults covered by the program are working. States would also have to recertify Medicaid expansion enrollees’ eligibility every six months, rather than once a year or less, as most states currently do.

The bill would also freeze states’ practice of taxing hospitals, nursing homes, managed-care plans, and other health care companies to fund their share of Medicaid costs.

The Congressional Budget Office said in a May 11 preliminary estimate that, under the House-passed bill, about 8.6 million more people would be without health insurance in 2034. That number will rise to nearly 14 million, the CBO estimates, after the Trump administration finishes new ACA regulations and if the Republican-led Congress, as expected, declines to extend enhanced premium subsidies for commercial insurance plans sold through Obamacare marketplaces.

The enhanced subsidies, a priority of former President Joe Biden, eliminated monthly premiums altogether for some people buying Obamacare plans. They are set to expire at the end of the year.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

5 months 6 days ago

california, Health Care Costs, Insurance, Medicaid, States, Colorado, Connecticut, District Of Columbia, Illinois, Immigrants, Legislation, Maine, Massachusetts, Medicaid Watch, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, U.S. Congress, Utah, Vermont, Washington

Los hospitales que atienden partos en zonas rurales están cada vez más lejos de las embarazadas

WINNER, Dakota del Sur — Sophie Hofeldt tenía previsto hacerse los controles de embarazo y dar a luz en el hospital local, a 10 minutos de su casa. En cambio, ahora, para ir a la consulta médica, tiene que conducir más de tres horas entre ida y vuelta.

Es que el hospital donde se atendía, Winner Regional Health, se ha sumado recientemente al cada vez mayor número de centros de salud rurales que cierran sus unidades de maternidad.

“Ahora va a ser mucho más estresante y complicado para las mujeres recibir la atención médica que necesitan, porque tienen que ir mucho más lejos”, dijo Hofeldt, que tiene fecha de parto de su primer hijo el 10 de junio.

Hofeldt agregó que los viajes más largos suponen más gasto en gasolina y un mayor riesgo de no llegar a tiempo al hospital. “Mi principal preocupación es tener que parir en un auto”, afirma.

Más de un centenar de hospitales rurales han dejado de atender partos desde 2021, según el Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, una organización sin fines de lucro. El cierre de los servicios de obstetricia se suele achacar a la falta de personal y la falta de presupuesto.

En la actualidad, alrededor del 58% de los condados de Dakota del Sur no cuentan con salas de parto. Es la segunda tasa más alta del país, después de Dakota del Norte, según March of Dimes, una organización que asiste a las madres y sus bebés.

Además, el Departamento de Salud de Dakota del Sur informó que las mujeres embarazadas y los bebés del estado — especialmente las afroamericanas y las nativas americanas— presentan tasas más altas de complicaciones y mortalidad.

Winner Regional Health atiende a comunidades rurales en Dakota del Sur y Nebraska, incluyendo parte de la reserva indígena Rosebud Sioux. El año pasado nacieron allí 107 bebés, una baja considerable respecto de los 158 que nacieron en 2021, contó su director ejecutivo, Brian Williams.

Los hospitales más cercanos con servicios de maternidad se encuentran en pueblos rurales a una hora de distancia, o más, de Winner.

Sin embargo, varias mujeres afirmaron que el trayecto en coche hasta esos centros las llevaría por zonas donde no hay señal de celular confiable, lo que podría suponer un problema si tuvieran una emergencia en el camino.

KFF Health News habló con cinco pacientes de la zona de Winner que tenían previsto que su parto fuera en el Avera St. Mary’s Hospital de Pierre, a unas 90 millas de Winner, o en uno de los grandes centros médicos de Sioux Falls, a 170 millas de distancia.

Hofeldt y su novio conducen cada tres semanas para ir a las citas prenatales en el hospital de Pierre, que brinda servicios a la pequeña capital y a la vasta zona rural circundante.

A medida que se acerque la fecha del parto, las citas de control y, por lo tanto los viajes, tendrán que ser semanales. Ninguno de los dos tiene un empleo que le brinde permiso con goce de sueldo para ese tipo de consulta médica.

“Cuando necesitamos ir a Pierre, tenemos que tomarnos casi todo el día libre”, explicó Hofeldt, que nació en el hospital de Winner.

Eso significa perder una parte del salario y gastar dinero extra en el viaje. Además, no todo el mundo tiene auto ni dinero para la gasolina, y los servicios de autobús son escasos en las zonas rurales del país.

Algunas mujeres también tienen que pagar el cuidado de sus otros hijos para poder ir al médico cuando el hospital está lejos. Y, cuando nace el bebé, tal vez tengan que asumir el costo de un hotel para los familiares.

Amy Lueking, la médica que atiende a Hofeldt en Pierre, dijo que cuando las pacientes no pueden superar estas barreras, los obstetras tienen la opción de darles dispositivos para monitorear el embarazo en el hogar y ofrecerles consulta por teléfono o videoconferencia.

Las pacientes también pueden hacerse los controles prenatales en un hospital o una clínica local y, más tarde, ponerse en contacto con un profesional de un hospital donde se practiquen partos, dijo Lueking.

Sin embargo, algunas zonas rurales no tienen acceso a la telesalud. Y algunas pacientes, como Hofeldt, no quieren dividir su atención, establecer relaciones con dos médicos y ocuparse de cuestiones logísticas como transferir historias clínicas.

Durante una cita reciente, Lueking deslizó un dispositivo de ultrasonido sobre el útero de Hofeldt. El ritmo de los latidos del corazón del feto resonó en el monitor.

“Creo que es el mejor sonido del mundo”, expresó Lueking.

Hofeldt le comentó que quería un parto lo más natural posible.

Pero lograr que el parto se desarrolle según lo planeado suele ser complicado para quienes viven en zonas rurales, lejos del hospital. Para estar seguras de que llegarán a tiempo, algunas mujeres optan por programar una inducción, un procedimiento en el que los médicos utilizan medicamentos u otras técnicas para provocar el trabajo de parto.

Katie Larson vive en un rancho cerca de Winner, en la localidad de Hamill, que tiene 14 habitantes. Esperaba evitar que le indujeran el parto.

Larson quería esperar a que las contracciones comenzaran de forma natural y luego conducir hasta el Avera St. Mary’s, en Pierre.

Pero terminó programando una inducción para el 13 de abril, su fecha probable de parto. Más tarde, la adelantó al 8 de abril para no perderse una venta de ganado muy importante, que ella y su esposo estaban preparando.

“La gente se verá obligada a elegir una fecha de inducción aunque no sea lo que en un principio hubiera elegido. Si no, correrá el riesgo de tener al bebé en la carretera”, afirmó.

Lueking aseguró que no es frecuente que las embarazadas den a luz mientras se dirigen al hospital en automóvil o en ambulancia. Pero también recordó que el año anterior cinco mujeres que tenían previsto tener a sus hijos en Pierre acabaron haciéndolo en las salas de emergencias de otros hospitales, porque el parto avanzó muy rápido o porque las condiciones del clima hicieron demasiado peligroso conducir largas distancias.

Nanette Eagle Star tenía previsto que su bebé naciera en el hospital de Winner, a cinco minutos de su casa, hasta que el hospital anunció que cerraría su unidad de maternidad. Entonces decidió dar a luz en Sioux Falls, porque su familia podía quedarse con unos familiares que vivían allí y así ahorrar dinero.

El plan de Eagle Star volvió a cambiar cuando comenzó el trabajo de parto prematuramente y el clima se puso demasiado peligroso para manejar o para tomar un helicóptero médico a Sioux Falls.

“Todo ocurrió muy rápido, en medio de una tormenta de nieve”, contó.

Finalmente, Eagle Star tuvo a su bebé en el hospital de Winner, pero en la sala de emergencias, sin epidural, ya que en ese momento no había ningún anestesista disponible. Esto ocurrió solo tres días después del cierre de la unidad de maternidad.

El fin de los servicios de parto y maternidad en el Winner Regional Health no es solo un problema de salud, según las mujeres de la localidad. También tiene repercusiones emocionales y económicas en la comunidad.

Eagle Star recuerda con cariño cuando era niña e iba con sus hermanas a las citas médicas. Apenas llegaban, iban a un pasillo que tenía fotos de bebés pegadas en la pared y comenzaban una “búsqueda del tesoro” para encontrar polaroids de ellas mismas y de sus familiares.

“A ambos lados del pasillo estaba lleno de fotos de bebés”, contó Eagle Star. Recuerda pensar: “Mira todos estos bebés tan lindos que han nacido aquí, en Winner”.

Hofeldt contó que muchos lugareños están tristes porque sus bebés no nacerán en el mismo hospital que ellos.

Anora Henderson, médica de familia, señaló que la falta de una correcta atención a las mujeres embarazadas puede tener consecuencias negativas para sus hijos. Esos bebés pueden desarrollar problemas de salud que requerirán cuidados de por vida, a menudo costosos, y otras ayudas públicas.

“Hay un efecto negativo en la comunidad”, dijo. “Simplemente no es tan visible y se notará bastante más adelante”.

Henderson renunció en mayo a su puesto en el Winner Regional Health, donde asistía partos vaginales y ayudaba en las cesáreas. El último bebé al que recibió fue el de Eagle Star.

Para que un centro de salud sea designado como hospital con servicio de maternidad, debe contar con instalaciones donde se pueden efectuar cesáreas y proporcionar anestesia las 24 horas del día, los 7 días de la semana, explicó Henderson.

Williams, el director ejecutivo del hospital, dijo que el Winner Regional Health no ha podido contratar suficientes profesionales médicos con formación en esas especializaciones.

En los últimos años, el hospital solo había podido ofrecer servicios de maternidad cubriendo aproximadamente $1,2 millones anuales en salarios de médicos contratados de forma temporal, señaló. Pero el hospital ya no podía seguir asumiendo ese gasto.

Otro reto financiero está dado porque muchos partos en los hospitales rurales están cubiertos por Medicaid, el programa federal y estatal que ofrece atención a personas con bajos ingresos o discapacidades.

El programa suele pagar aproximadamente la mitad de lo que pagan las aseguradoras privadas por los servicios de parto, según un informe de 2022 de la U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Williams contó que alrededor del 80% de los partos en Winner Regional Health estaban cubiertos por Medicaid.

Las unidades obstétricas suelen constituir el mayor gasto financiero de los hospitales rurales y, por lo tanto, son las primeras que se cierran cuando un centro de salud atraviesa dificultades económicas, explica el informe de la GAO.

Williams dijo que el hospital sigue prestando atención prenatal y que le encantaría reanudar los partos si pudiera contratar suficiente personal.

Henderson, la médica que dimitió del hospital de Winner, ha sido testigo del declive de la atención materna en las zonas rurales durante décadas.

Recuerda que, antes de que naciera su hermana, acompañaba a su madre a las citas médicas. En cada viaje, su madre recorría unas 100 millas después de que el hospital de la ciudad de Kadoka cerrara en 1979.

Henderson trabajó durante casi 22 años en el Winner Regional Health, lo que permitió que muchas mujeres no tuvieran que desplazarse para dar a luz, como le ocurrió a su madre.

A lo largo de los años, atendió a nuevas pacientes cuando cerraron las unidades de maternidad de un hospital rural cercano y luego las de un centro del Servicio de Salud Indígena. Finalmente, el propio hospital de Henderson dejó de atender partos.

“Lo que ahora realmente me frustra es que pensaba que iba a dedicarme a la medicina familiar y trabajar en una zona rural, y que así íbamos a solucionar estos problemas, para que las personas no tuvieran que conducir 100 millas para tener un bebé”, se lamentó.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

5 months 1 week ago

Health Care Costs, Health Industry, Medicaid, Noticias En Español, Rural Health, States, Hospitals, North Dakota, Pregnancy, South Dakota, Women's Health

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

After narrowly passing a budget resolution this spring foreshadowing major Medicaid cuts, Republicans in Congress are having trouble agreeing on specific ways to save billions of dollars from a pool of funding that pays for the program without cutting benefits on which millions of Americans rely. Moderates resist changes they say would harm their constituents, while fiscal conservatives say they won’t vote for smaller cuts than those called for in the budget resolution. The fate of President Donald Trump’s “one big, beautiful bill” containing renewed tax cuts and boosted immigration enforcement could hang on a Medicaid deal.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration surprised those on both sides of the abortion debate by agreeing with the Biden administration that a Texas case challenging the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone should be dropped. It’s clear the administration’s request is purely technical, though, and has no bearing on whether officials plan to protect the abortion pill’s availability.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Anna Edney of Bloomberg News, Maya Goldman of Axios, and Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Anna Edney

Bloomberg News

Maya Goldman

Axios

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- Congressional Republicans are making halting progress on negotiations over government spending cuts. As hard-line House conservatives push for deeper cuts to the Medicaid program, their GOP colleagues representing districts that heavily depend on Medicaid coverage are pushing back. House Republican leaders are eying a Memorial Day deadline, and key committees are scheduled to review the legislation next week — but first, Republicans need to agree on what that legislation says.

- Trump withdrew his nomination of Janette Nesheiwat for U.S. surgeon general amid accusations she misrepresented her academic credentials and criticism from the far right. In her place, he nominated Casey Means, a physician who is an ally of HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s and a prominent advocate of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

- The pharmaceutical industry is on alert as Trump prepares to sign an executive order directing agencies to look into “most-favored-nation” pricing, a policy that would set U.S. drug prices to the lowest level paid by similar countries. The president explored that policy during his first administration, and the drug industry sued to stop it. Drugmakers are already on edge over Trump’s plan to impose tariffs on drugs and their ingredients.

- And Kennedy is scheduled to appear before the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee next week. The hearing would be the first time the secretary of Health and Human Services has appeared before the HELP Committee since his confirmation hearings — and all eyes are on the committee’s GOP chairman, Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a physician who expressed deep concerns at the time, including about Kennedy’s stances on vaccines.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and co-wrote the latest KFF Health News’ “Bill of the Month” installment, about an unexpected bill for what seemed like preventive care. If you have an outrageous, baffling, or infuriating medical bill you’d like to share with us, you can do that here.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: NPR’s “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured,” by Andrea Hsu.

Maya Goldman: Stat’s “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph.

Anna Edney: Bloomberg News’ “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare,” by Zachary R. Mider and Zeke Faux.

Sandhya Raman: The Louisiana Illuminator’s “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” by Anna Claire Vollers.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- ProPublica’s series “Life of the Mother: How Abortion Bans Lead to Preventable Deaths,” by Kavitha Surana, Lizzie Presser, Cassandra Jaramillo, and Stacy Kranitz, and the winner of the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for public service journalism.

- The New York Times’ “G.O.P. Targets a Medicaid Loophole Used by 49 States To Grab Federal Money,” by Margot Sanger-Katz and Sarah Kliff.

- KFF Health News’ “Seeking Spending Cuts, GOP Lawmakers Target a Tax Hospitals Love to Pay,” by Phil Galewitz.

- Axios’ “Out-of-Pocket Drug Spending Hit $98B in 2024: Report,” by Maya Goldman.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, May 8, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via a videoconference by Anna Edney of Bloomberg News.

Anna Edney: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Maya Goldman of Axios News.

Maya Goldman: Great to be here.

Rovner: And Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning, everyone.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have my “Bill of the Month” interview with my KFF Health News colleague Lauren Sausser. This month’s patient got preventive care they assumed would be covered by their Affordable Care Act health plan, except it wasn’t. But first, this week’s news.

We’re going to start on Capitol Hill, where Sandhya is coming directly from, where regular listeners to this podcast will be not one bit surprised that Republicans working on President [Donald] Trump’s one “big, beautiful” budget reconciliation bill are at an impasse over how and how deeply to cut the Medicaid program. Originally, the House Energy and Commerce Committee was supposed to mark up its portion of the bill this week, but that turned out to be too optimistic. Now they’re shooting for next week, apparently Tuesday or so, they’re saying, and apparently that Memorial Day goal to finish the bill is shifting to maybe the Fourth of July? But given what’s leaking out of the closed Republican meetings on this, even that might be too soon. Where are we with these Medicaid negotiations?

Raman: I would say a lot has been happening, but also a lot has not been happening. I think that anytime we’ve gotten any little progress on knowing what exactly is at the top of the list, it gets walked back. So earlier this week we had a meeting with a lot of the moderates in Speaker [Mike] Johnson’s office and trying to get them on board with some of the things that they were hesitant about, and following the meeting, Speaker Johnson had said that two of the things that have been a little bit more contentious — changing the federal match for the expansion population and instituting per capita caps for states — were off the table. But the way that he phrased it is kind of interesting in that he said stay tuned and that it possibly could change.

And so then yesterday when we were hearing from the Energy and Commerce Committee, it seemed like these things are still on the table. And then Speaker Johnson has kind of gone back on that and said, I said it was likely. So every time we kind of have any sort of change, it’s really unclear if these things are in the mix, outside the mix. When we pulled them off the table, we had a lot of the hard-line conservatives get really upset about this because it’s not enough savings. So I think any way that you push it with such narrow margins, it’s been difficult to make any progress, even though they’ve been having a lot of meetings this week.

Rovner: One of the things that surprised me was apparently the Senate Republicans are weighing in. The Senate Republicans who aren’t even set to make Medicaid cuts under their version of the budget resolution are saying that the House needs to go further. Where did that come from?

Raman: It’s just been a difficult process to get anything across. I mean, in the House side, a lot of it has been, I think, election-driven. You see the people that are not willing to make as many concessions are in competitive districts. The people that want to go a little bit more extreme on what they’re thinking are in much more safe districts. And then in the Senate, I think there’s a lot more at play just because they have longer terms, they have more to work with. So some of the pushback has been from people that it would directly affect their states or if the governors have weighed in. But I think that there are so many things that they do want to get done, since there is much stronger agreement on some of the immigration stuff and the taxes that they want to find the savings somewhere. If they don’t find it, then the whole thing is moot.

Rovner: So meanwhile, the Congressional Budget Office at the request of Democrats is out with estimates of what some of these Medicaid options would mean for coverage, and it gives lie to some of these Republican claims that they can cut nearly a trillion dollars from Medicaid without touching benefits, right? I mean all of these — and Maya, your nodding.

Goldman: Yeah.

Rovner: All of these things would come with coverage losses.

Goldman: Yeah, I think it’s important to think about things like work requirements, which has gotten a lot of support from moderate Republicans. The only way that that produces savings is if people come off Medicaid as a result. Work requirements in and of themselves are not saving any money. So I know advocates are very concerned about any level of cuts. I talked to somebody from a nursing home association who said: We can’t pick and choose. We’re not in a position to pick and choose which are better or worse, because at this point, everything on the table is bad for us. So I think people are definitely waiting with bated breath there.

Rovner: Yeah, I’ve heard a lot of Republicans over the last week or so with the talking points. If we’re just going after fraud and abuse then we’re not going to cut anybody’s benefits. And it’s like — um, good luck with that.

Goldman: And President Trump has said that as well.

Rovner: That’s right. Well, one place Congress could recoup a lot of money from Medicaid is by cracking down on provider taxes, which 49 of the 50 states use to plump up their federal Medicaid match, if you will. Basically the state levies a tax on hospitals or nursing homes or some other group of providers, claims that money as their state share to draw down additional federal matching Medicaid funds, then returns it to the providers in the form of increased reimbursement while pocketing the difference. You can call it money laundering as some do, or creative financing as others do, or just another way to provide health care to low-income people.

But one thing it definitely is, at least right now, is legal. Congress has occasionally tried to crack down on it since the late 1980s. I have spent way more time covering this fight than I wish I had, but the combination of state and health provider pushback has always prevented it from being eliminated entirely. If you want a really good backgrounder, I point you to the excellent piece in The New York Times this week by our podcast pals Margot Sanger-Katz and Sarah Kliff. What are you guys hearing about provider taxes and other forms of state contributions and their future in all of this? Is this where they’re finally going to look to get a pot of money?

Raman: It’s still in the mix. The tricky thing is how narrow the margins are, and when you have certain moderates having a hard line saying, I don’t want to cut more than $500 billion or $600 billion, or something like that. And then you have others that don’t want to dip below the $880 billion set for the Energy and Commerce Committee. And then there are others that have said it’s not about a specific number, it’s what is being cut. So I think once we have some more numbers for some of the other things, it’ll provide a better idea of what else can fit in. Because right now for work requirements, we’re going based on some older CBO [Congressional Budget Office] numbers. We have the CBO numbers that the Democrats asked for, but it doesn’t include everything. And piecing that together is the puzzle, will illuminate some of that, if there are things that people are a little bit more on board with. But it’s still kind of soon to figure out if we’re not going to see draft text until early next week.

Goldman: I think the tricky thing with provider taxes is that it’s so baked into the way that Medicaid functions in each state. And I think I totally co-sign on the New York Times article. It was a really helpful explanation of all of this, and I would bet that you’ll see a lot of pushback from state governments, including Republicans, on a proposal that makes severe changes to that.

Rovner: Someday, but not today, I will tell the story of the 1991 fight over this in which there was basically a bizarre dealmaking with individual senators to keep this legal. That was a year when the Democrats were trying to get rid of it. So it’s a bipartisan thing. All right, well, moving on.

It wouldn’t be a Thursday morning if we didn’t have breaking federal health personnel news. Today was supposed to be the confirmation hearing for surgeon general nominee and Fox News contributor Janette Nesheiwat. But now her nomination has been pulled over some questions about whether she was misrepresenting her medical education credentials, and she’s already been replaced with the nomination of Casey Means, the sister of top [Health and Human Services] Secretary [Robert F.] Kennedy [Jr.] aide Calley Means, who are both leaders in the MAHA [“Make America Healthy Again”] movement. This feels like a lot of science deniers moving in at one time. Or is it just me?

Edney: Yeah, I think that the Meanses have been in this circle, names floated for various things at various times, and this was a place where Casey Means fit in. And certainly she espouses a lot of the views on, like, functional medicine and things that this administration, at least RFK Jr., seems to also subscribe to. But the one thing I’m not as clear on her is where she stands with vaccines, because obviously Nesheiwat had fudged on her school a little bit, and—

Rovner: Yeah, I think she did her residency at the University of Arkansas—

Edney: That’s where.

Rovner: —and she implied that she’d graduated from the University of Arkansas medical school when in fact she graduated from an accredited Caribbean medical school, which lots of doctors go to. It’s not a sin—

Edney: Right.

Rovner: —and it’s a perfectly, as I say, accredited medical school. That was basically — but she did fudge it on her resume.

Edney: Yeah.

Rovner: So apparently that was one of the things that got her pulled.

Edney: Right. And the other, kind of, that we’ve seen in recent days, again, is Laura Loomer coming out against her because she thinks she’s not anti-vaccine enough. So what the question I think to maybe be looking into today and after is: Is Casey Means anti-vaccine enough for them? I don’t know exactly the answer to that and whether she’ll make it through as well.

Rovner: Well, we also learned this week that Vinay Prasad, a controversial figure in the covid movement and even before that, has been named to head the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] Center for Biologics and Evaluation Research, making him the nation’s lead vaccine regulator, among other things. Now he does have research bona fides but is a known skeptic of things like accelerated approval of new drugs, and apparently the biotech industry, less than thrilled with this pick, Anna?

Edney: Yeah, they are quite afraid of this pick. You could see it in the stocks for a lot of vaccine companies, for some other companies particularly. He was quite vocal and quite against the covid vaccines during covid and even compared them to the Nazi regime. So we know that there could be a lot of trouble where, already, you know, FDA has said that they’re going to require placebo-controlled trials for new vaccines and imply that any update to a covid vaccine makes it a new vaccine. So this just spells more trouble for getting vaccines to market and quickly to people. He also—you mentioned accelerated approval. This is a way that the FDA uses to try to get promising medicines to people faster. There are issues with it, and people have written about the fact that they rely on what are called surrogate endpoints. So not Did you live longer? but Did your tumor shrink?

And you would think that that would make you live longer, but it actually turns out a lot of times it doesn’t. So you maybe went through a very strong medication and felt more terrible than you might have and didn’t extend your life. So there’s a lot of that discussion, and so that. There are other drugs. Like this Sarepta drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a big one that Vinay Prasad has come out against, saying that should have never been approved, because it was using these kind of surrogate endpoints. So I think biotech’s pretty — thinking they’re going to have a lot tougher road ahead to bring stuff to market.

Rovner: And I should point out that over the very long term, this has been the continuing struggle at FDA. It’s like, do you protect the public but make people wait longer for drugs or do you get the drugs out and make sure that people who have no other treatments available have something available? And it’s been a constant push and pull. It’s not really been partisan. Sometimes you get one side pushing and the other side pushing back. It’s really nothing new. It’s just the sort of latest iteration of this.

Edney: Right. Yeah. This is the pendulum swing, back to the Maybe we need to be slowing it down side. It’s also interesting because there are other discussions from RFK Jr. that, like, We need to be speeding up approvals and Trump wants to speed up approvals. So I don’t know where any of this will actually come down when the rubber meets the road, I guess.

Rovner: Sandhya and Maya, I see you both nodding. Do you want to add something?

Raman: I think this was kind of a theme that I also heard this week in the — we had the Senate Finance hearing for some of the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] nominees, and Jim O’Neill, who’s one of the nominees, that was something that was brought up by Finance ranking member Ron Wyden, that some of his past remarks when he was originally considered to be on the short list for FDA commissioner last Trump administration is that he basically said as long as it’s safe, it should go ahead regardless of efficacy. So those comments were kind of brought back again, and he’s in another hearing now, so that might come up as an issue in HELP [the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions] today.

Rovner: And he’s the nominee for deputy secretary, right? Have to make sure I keep all these things straight. Maya, you wanting to add something?

Goldman: Yeah, I was just going to say, I think there is a divide between these two philosophies on pharmaceuticals, and my sense is that the selection of Prasad is kind of showing that the anti-accelerated-approval side is winning out. But I think Anna is correct that we still don’t know where it’s going to land.

Rovner: Yes, and I will point out that accelerated approval first started during AIDS when there was no treatments and basically people were storming the — literally physically storming — the FDA, demanding access to AIDS drugs, which they did finally get. But that’s where accelerated approval came from. This is not a new fight, and it will continue.

Turning to abortion, the Trump administration surprised a lot of people this week when it continued the Biden administration’s position asking for that case in Texas challenging the abortion pill to be dropped. For those who’ve forgotten, this was a case originally filed by a bunch of Texas medical providers demanding the judge overrule the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone in the year 2000. The Supreme Court ruled the original plaintiff lacked standing to sue, but in the meantime, three states —Missouri, Idaho, and Kansas — have taken their place as plaintiffs. But now the Trump administration points out that those states have no business suing in the Northern District of Texas, which kind of seems true on its face. But we should not mistake this to think that the Trump administration now supports the current approval status of the abortion bill. Right, Sandhya?

Raman: Yeah, I think you’re exactly right. It doesn’t surprise me. If they had allowed these three states, none of which are Texas — they shouldn’t have standing. And if they did allow them to, that would open a whole new can of worms for so many other cases where the other side on so many issues could cherry-pick in the same way. And so I think, I assume, that this will come up in future cases for them and they will continue with the positions they’ve had before. But this was probably in their best interest not to in this specific one.

Rovner: Yeah. There are also those who point out that this could be a way of the administration protecting itself. If it wants to roll back or reimpose restrictions on the abortion pill, it would help prevent blue states from suing to stop that. So it serves a double purpose here, right?

Raman: Yeah. I couldn’t see them doing it another way. And even if you go through the ruling, the language they use, it’s very careful. It’s not dipping into talking fully about abortion. It’s going purely on standing. Yeah.

Rovner: There’s nothing that says, We think the abortion pill is fine the way it is. It clearly does not say that, although they did get the headlines — and I’m sure the president wanted — that makes it look like they’re towing this middle ground on abortion, which they may be but not necessarily in this case.

Well, before we move off of reproductive health, a shoutout here to the incredible work of ProPublica, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for public service this week for its stories on women who died due to abortion bans that prevented them from getting care for their pregnancy complications. Regular listeners of the podcast will remember that we talked about these stories as they came out last year, but I will post another link to them in the show notes today.

OK, moving on. There’s even more drug price news this week, starting with the return of, quote, “most favored nation” drug pricing. Anna, remind us what this is and why it’s controversial.

Edney: Yeah. So the idea of most favored nation, this is something President Trump has brought up before in his first administration, but it creates a basket, essentially, of different prices that nations pay. And we’re going to base ours on the lowest price that is paid for—

Rovner: We’re importing other countries’—

Edney: —prices.

Rovner: —price limits.

Edney: Yeah. Essentially, yes. We can’t import their drugs, but we can import their prices. And so the goal is to just basically piggyback off of whoever is paying the lowest price and to base ours off of that. And clearly the drug industry does not like this and, I think, has faced a number of kind of hits this week where things are looming that could really come after them. So Politico broke that news that Trump is going to sign or expected to sign an executive order that will direct his agencies to look into this most-favored-nation effort. And it feels very much like 2.0, like we were here before. And it didn’t exactly work out, obviously.

Rovner: They sued, didn’t they? The drug industry sued, as I recall.

Edney: Yeah, I think you’re right. Yes.

Goldman: If I’m remembering—

Rovner: But I think they won.

Goldman: If I’m remembering correctly, it was an Administrative Procedure Act lawsuit though, right? So—

Rovner: It was. Yes. It was about a regulation. Yes.

Goldman: —who knows what would happen if they go through a different procedure this time.

Rovner: So the other thing, obviously, that the drug industry is freaked out about right now are tariffs, which have been on again, off again, on again, off again. Where are we with tariffs on — and it’s not just tariffs on drugs being imported. It’s tariffs on drug ingredients being imported, right?

Edney: Yeah. And that’s a particularly rough one because many ingredients are imported, and then some of the drugs are then finished here, just like a car. All the pieces are brought in and then put together in one place. And so this is something the Trump administration has began the process of investigating. And PhRMA [Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America], the trade group for the drug industry, has come out officially, as you would expect, against the tariffs, saying that: This will reduce our ability to do R&D. It will raise the price of drugs that Americans pay, because we’re just going to pass this on to everyone. And so we’re still in this waiting zone of seeing when or exactly how much and all of that for the tariffs for pharma.

Rovner: And yet Americans are paying — already paying — more than they ever have. Maya, you have a story just about that. Tell us.

Goldman: Yeah, there was a really interesting report from an analytics data firm that showed the price that Americans are paying for prescriptions is continuing to climb. Also, the number of prescriptions that Americans are taking is continuing to climb. It certainly will be interesting to see if this administration can be any more successful. That report, I don’t think this made it into the article that I ended up writing, but it did show that the cost of insulin is down. And that’s something that has been a federal policy intervention. We haven’t seen a lot of the effects yet of the Medicare drug price negotiations, but I think there are signs that that could lower the prices that people are paying. So I think it’s interesting to just see the evolution of all of this. It’s very much in flux.

Rovner: A continuing effort. Well, we are now well into the second hundred days of Trump 2.0, and we’re still learning about the cuts to health and health-related programs the administration is making. Just in this week’s rundown are stories about hundreds more people being laid off at the National Cancer Institute, a stop-work order at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases research lab at Fort Detrick, Maryland, that studies Ebola and other deadly infectious diseases, and the layoff of most of the remaining staff at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

A reminder that this is all separate from the discretionary-spending budget request that the administration sent up to lawmakers last week. That document calls for a 26% cut in non-mandatory funding at HHS, meaning just about everything other than Medicare and Medicaid. And it includes a proposed $18 billion cut to the NIH [National Institutes of Health] and elimination of the $4 billion Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps millions of low-income Americans pay their heating and air conditioning bills. Now, this is normally the part of the federal budget that’s deemed dead on arrival. The president sends up his budget request, and Congress says, Yeah, we’re not doing that. But this at least does give us an idea of what direction the administration wants to take at HHS, right? What’s the likelihood of Congress endorsing any of these really huge, deep cuts?

Raman: From both sides—

Rovner: Go ahead, Sandhya.

Raman: It’s not going to happen, and they need 60 votes in the Senate to pass the appropriations bills. I think that when we’re looking in the House in particular, there are a lot of things in what we know from this so-called skinny budget document that they could take up and put in their bill for Labor, HHS, and Education. But I think the Senate’s going to be a different story, just because the Senate Appropriations chair is Susan Collins and she, as soon as this came out, had some pretty sharp words about the big cuts to NIH. They’ve had one in a series of two hearings on biomedical research. Concerned about some of these kinds of things. So I cannot necessarily see that sharp of a cut coming to fruition for NIH, but they might need to make some concessions on some other things.

This is also just a not full document. It has some things and others. I didn’t see any to FDA in there at all. So that was a question mark, even though they had some more information in some of the documents that had leaked kind of earlier on a larger version of this budget request. So I think we’ll see more about how people are feeling next week when we start having Secretary Kennedy testify on some of these. But I would not expect most of this to make it into whatever appropriations law we get.

Goldman: I was just going to say that. You take it seriously but not literally, is what I’ve been hearing from people.

Edney: We don’t have a full picture of what has already been cut. So to go in and then endorse cutting some more, maybe a little bit too early for that, because even at this point they’re still bringing people back that they cut. They’re finding out, Oh, this is actually something that is really important and that we need, so to do even more doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense right now.

Rovner: Yeah, that state of disarray is purposeful, I would guess, and doing a really good job at sort of clouding things up.

Goldman: One note on the cuts. I talked to someone at HHS this week who said as they’re bringing back some of these specialized people, in order to maintain the legality of, what they see as the legality of, the RIF [reduction in force], they need to lay off additional people to keep that number consistent. So I think that is very much in flux still and interesting to watch.

Rovner: Yeah, and I think that’s part of what we were seeing this week is that the groups that got spared are now getting cut because they’ve had to bring back other people. And as I point out, I guess, every week, pretty much all of this is illegal. And as it goes to courts, judges say, You can’t do this. So everything is in flux and will continue.

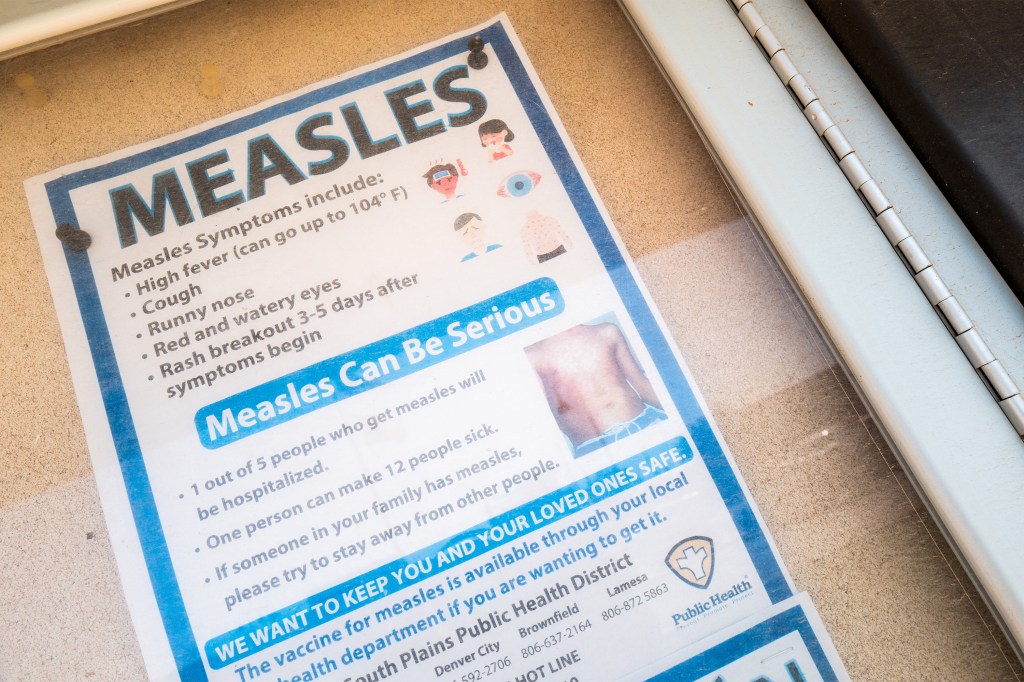

All right, finally this week, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who as of now is scheduled to appear before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee next week to talk about the department’s proposed budget, is asking CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] to develop new guidance for treating measles with drugs and vitamins. This comes a week after he ordered a change in vaccine policy you already mentioned, Anna, so that new vaccines would have to be tested against placebos rather than older versions of the vaccine. These are all exactly the kinds of things that Kennedy promised health committee chairman Bill Cassidy he wouldn’t do. And yet we’ve heard almost nothing from Cassidy about anything the secretary has said or done since he’s been in office. So what do we expect to happen when they come face-to-face with each other in front of the cameras next week, assuming that it happens?

Edney: I’m very curious. I don’t know. Do I expect a senator to take a stand? I don’t necessarily, but this—

Rovner: He hasn’t yet.

Edney: Yeah, he hasn’t yet. But this is maybe about face-saving too for him. So I don’t know.

Rovner: Face-saving for Kennedy or for Cassidy?

Edney: For Cassidy, given he said: I’m going to keep an eye on him. We’re going to talk all the time, and he is not going to do this thing without my input. I’m not sure how Cassidy will approach that. I think it’ll be a really interesting hearing that we’ll all be watching.

Rovner: Yes. And just little announcement, if it does happen, that we are going to do sort of a special Wednesday afternoon after the hearing with some of our KFF Health News colleagues. So we are looking forward to that hearing. All right, that is this week’s news. Now we will play my “Bill of the Month” interview with Lauren Sausser, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am pleased to welcome back to the podcast KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and wrote the latest KFF Health News “Bill of the Month.” Lauren, welcome back.

Lauren Sausser: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Rovner: So this month’s patient got preventive care, which the Affordable Care Act was supposed to incentivize by making it cost-free at the point of service — except it wasn’t. Tell us who the patient is and what kind of care they got.

Sausser: Carmen Aiken is from Chicago. Carmen uses they/them pronouns. And Carmen made an appointment in the summer of 2023 for an annual checkup. This is just like a wellness check that you are very familiar with. You get your vaccines updated. You get your weight checked. You talk to your doctor about your physical activity and your family history. You might get some blood work done. Standard stuff.

Rovner: And how big was the bill?

Sausser: The bill ended up being more than $1,400 when it should, in Carmen’s mind, have been free.

Rovner: Which is a lot.

Sausser: A lot.

Rovner: I assume that there was a complaint to the health plan and the health plan said, Nope, not covered. Why did they say that?

Sausser: It turns out that alongside with some blood work that was preventive, Carmen also had some blood work done to monitor an ongoing prescription. Because that blood test is not considered a standard preventive service, the entire appointment was categorized as diagnostic and not preventive. So all of these services that would’ve been free to them, available at no cost, all of a sudden Carmen became responsible for.

Rovner: So even if the care was diagnostic rather than strictly preventive — obviously debatable — that sounds like a lot of money for a vaccine and some blood test. Why was the bill so high?

Sausser: Part of the reason the bill was so high was because Carmen’s blood work was sent to a hospital for processing, and hospitals, as you know, can charge a lot more for the same services. So under Carmen’s health plan, they were responsible for, I believe it was, 50% of the cost of services performed in an outpatient hospital setting. And that’s what that blood work fell under. So the charges were high.

Rovner: So we’ve talked a lot on the podcast about this fight in Congress to create site-neutral payments. This is a case where that probably would’ve made a big difference.

Sausser: Yeah, it would. And there’s discussion, there’s bipartisan support for it. The idea is that you should not have to pay more for the same services that are delivered at different places. But right now there’s no legislation to protect patients like Carmen from incurring higher charges.

Rovner: So what eventually happened with this bill?

Sausser: Carmen ended up paying it. They put it on a credit card. This was of course after they tried appealing it to their insurance company. Their insurance company decided that they agreed with the provider that these services were diagnostic, not preventive. And so, yeah, Carmen was losing sleep over this and decided ultimately that they were just going to pay it.

Rovner: And at least it was a four-figure bill and not a five-figure bill.

Sausser: Right.

Rovner: What’s the takeaway here? I imagine it is not that you should skip needed preventive/diagnostic care. Some drugs, when you’re on them, they say that you should have blood work done periodically to make sure you’re not having side effects.

Sausser: Right. You should not skip preventive services. And that’s the whole intent behind this in the ACA. It catches stuff early so that it becomes more treatable. I think you have to be really, really careful and specific when you’re making appointments, and about your intention for the appointment, so that you don’t incur charges like this. I think that you can also be really careful about where you get your blood work conducted. A lot of times you’ll see these signs in the doctor’s office like: We use this lab. If this isn’t in-network with you, you need to let us know. Because the charges that you can face really vary depending on where those labs are processed. So you can be really careful about that, too.

Rovner: And adding to all of this, there’s the pending Supreme Court case that could change it, right?

Sausser: Right. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments. It was in April. I think it was on the 21st. And it is a case that originated out in Texas. There is a group of Christian businesses that are challenging the mandate in the ACA that requires health insurers to cover a lot of these preventive services. So obviously we don’t have a decision in the case yet, but we’ll see.

Rovner: We will, and we will cover it on the podcast. Lauren Sausser, thank you so much.

Sausser: Thank you.

Rovner: OK, we’re back. Now it’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s where we each recognize the story we read this week we think you should read, too. Don’t worry if you miss it. We will put the links in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Maya, you were the first to choose this week, so why don’t you go first?

Goldman: My extra credit is from Stat. It’s called “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph. And I just think it’s a really interesting evidence point to the United States’ losses, other countries’ gain. The U.S. has long been the pinnacle of research science, and people flock to this country to do research. And I think we’re already seeing a reversal of that as cuts to NIH funding and other scientific enterprises is reduced.

Rovner: Yep. A lot of stories about this, too. Anna.

Edney: So mine is from a couple of my colleagues that they did earlier this week. “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare.” And I thought it was really interesting because it had brought me back to these cheap, bare-bones plans that people were allowed to start selling that don’t meet any of the Obamacare requirements. And so this guy who used to, in the ’80s and ’90s, wrote for sitcoms — “Coach” or “Night Court,” if anyone goes to watch those on reruns. But he did a series of random things after that and has sort of now landed on selling these junk plans, but doing it in a really weird way that signs people up for a job that they don’t know they’re being signed up for. And I think it’s just, it’s an interesting read because we knew when these things were coming online that this was shady and people weren’t going to get the coverage they needed. And this takes it to an extra level. They’re still around, and they’re still ripping people off.

Rovner: Or as I’d like to subhead this story: Creative people think of creative things.

Edney: “Creative” is a nice word.

Rovner: Sandhya.

Raman: So my pick is “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” and it’s from Anna Claire Vollers at the Louisiana Illuminator. And her story looks at some of the ties between civil rights and health. So 2025 is the 70th anniversary of the bus boycott, the 60th anniversary of Selma-to-Montgomery marches, the Voting Rights Act. And it’s also the 60th anniversary of Medicaid. And she goes into, Medicaid isn’t something you usually consider a civil rights win, but health as a human right was part of the civil rights movement. And I think it’s an interesting piece.

Rovner: It is an interesting piece, and we should point out Medicare was also a huge civil rights, important piece of law because it desegregated all the hospitals in the South. All right, my extra credit this week is a truly infuriating story from NPR by Andrea Hsu. It’s called “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured.” And it’s a situation that if a private employer did it, Congress would be all over them and it would be making huge headlines. These are federal workers who are trying to do the right thing for themselves and their families but who are being jerked around in impossible ways and have no idea not just whether they have jobs but whether they have health insurance, and whether the medical care that they’re getting while this all gets sorted out will be covered. It’s one thing to shrink the federal workforce, but there is some basic human decency for people who haven’t done anything wrong, and a lot of now-former federal workers are not getting it at the moment.

OK, that is this week’s show. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate if you left us a review. That helps other people find us, too. Thanks as always to our editor, Emmarie Huetteman, and our producer, Francis Ying. Also, as always, you can email us your comments or questions, We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org, or you can still find me on X, @jrovner, or on Bluesky, @julierovner. Where are you folks hanging these days? Sandhya?

Raman: I’m on X, @SandhyaWrites, and also on Bluesky, @SandhyaWrites at Bluesky.

Rovner: Anna.

Edney: X and Bluesky, @annaedney.

Rovner: Maya.

Goldman: I am on X, @mayagoldman_. Same on Bluesky and also increasingly on LinkedIn.

Rovner: All right, we’ll be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

5 months 3 weeks ago

Courts, COVID-19, Health Care Costs, Insurance, Medicaid, Multimedia, Pharmaceuticals, Public Health, States, The Health Law, Abortion, Bill Of The Month, Drug Costs, FDA, HHS, Hospitals, KFF Health News' 'What The Health?', NIH, Podcasts, Prescription Drugs, Preventive Services, reproductive health, Surprise Bills, Trump Administration, U.S. Congress, vaccines, Women's Health

Aumenta la desinformación sobre el sarampión, y las personas le prestan atención, dice una encuesta

Mientras la epidemia de sarampión más grave en una década ha causado la muerte de dos niños y se ha extendido a 27 estados sin dar señales de desacelerar, las creencias sobre la seguridad de la vacuna contra esta infección y la amenaza de la enfermedad se polarizan rápido, alimentadas por las opiniones antivacunas del funcionario de salud de mayor rango del país.

Aproximadamente dos tercios de los padres con inclinaciones republicanas desconocen el aumento en los casos de sarampión este año, mientras que cerca de dos tercios de los demócratas sabían sobre el tema, según una encuesta de KFF publicada el miércoles 23 de abril.

Los republicanos son mucho más escépticos con respecto a las vacunas y tienen el doble de probabilidades (1 de cada 5) que los demócratas (1 de cada 10) de creer que la vacuna contra el sarampión es peor que la enfermedad, según la encuesta realizada a 1.380 adultos estadounidenses.

Alrededor del 35% de los republicanos que respondieron a la encuesta, realizada del 8 al 15 de abril por internet y por teléfono, aseguraron que la teoría desacreditada que vincula la vacuna contra el sarampión, las paperas y la rubéola con el autismo era definitiva o probablemente cierta, en comparación con solo el 10% de los demócratas.

Las tendencias son prácticamente las mismas que las reportadas por KFF en una encuesta de junio de 2023.

Sin embargo, en la nueva encuesta, 3 de cada 10 padres creían erróneamente que la vitamina A puede prevenir las infecciones por el virus del sarampión, una teoría que Robert F. Kennedy Jr., el secretario de Salud y Servicios Humanos, ha diseminado desde que asumió el cargo, en medio del brote de sarampión.

Se han reportado alrededor de 900 casos en 27 estados, la mayoría en un brote centrado en el oeste de Texas.

“Lo más alarmante de la encuesta es que estamos observando un aumento en la proporción de personas que han escuchado estas afirmaciones”, afirmó la coautora Ashley Kirzinger, directora asociada del Programa de Investigación de Encuestas y Opinión Pública de KFF. (KFF es una organización sin fines de lucro dedicada a la información sobre salud que incluye a KFF Health News).

“No es que más gente crea en la teoría del autismo, sino que cada vez más gente escucha sobre ella”, afirmó Kirzinger. Debido a que las dudas sobre la seguridad de las vacunas es factor directo de la decision de los padres reducer la vacunación de sus hijos, “esto demuestra la importancia de que la información veraz forme parte del panorama mediático”, añadió.

“Esto es lo que cabría esperar cuando la gente está confundida por mensajes contradictorios provenientes de personas en posiciones de autoridad”, afirmó Kelly Moore, presidenta y directora ejecutiva de Immunize.org, un grupo de defensa de la vacunación.

Numerosos estudios científicos no han establecido ningún vínculo entre cualquier vacuna y el autismo. Sin embargo, Kennedy ha ordenado al Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos (HHS) que realice una investigación sobre los posibles factores ambientales que contribuyen al autismo, prometiendo tener “algunas de las respuestas” sobre el aumento en la incidencia de la afección para septiembre.

La profundización del escepticismo republicano hacia las vacunas dificulta la difusión de información precisa en muchas partes del país, afirmó Rekha Lakshmanan, directora de estrategia de The Immunization Partnership, en Houston.

El 23 de abril, Lakshmanan iba a presentar un documento sobre cómo contrarrestar el activismo antivacunas ante el Congreso Mundial de Vacunas en Washington. El documento se basaba en una encuesta que reveló que, en las asambleas estatales de Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas y Oklahoma, los legisladores con profesiones médicas se encontraban entre los menos propensos a apoyar las medidas de salud pública.

“Hay un componente político que influye en estos legisladores”, afirmó. Por ejemplo, cuando los legisladores invitan a quienes se oponen a las vacunas a testificar en las audiencias legislativas, se alimenta una avalancha de desinformación difícil de refutar, agregó.

Eric Ball, pediatra de Ladera Ranch, California, área afectada por un brote de sarampión en 2014-2015 que comenzó en Disneyland, afirmó que el miedo al sarampión y las restricciones más estrictas del estado de California sobre las exenciones de vacunas evitaron nuevas infecciones en su comunidad del condado de Orange.

“La mayor desventaja de las vacunas contra el sarampión es que funcionan muy bien. Todos se vacunan, nadie contrae sarampión, todos se olvidan del sarampión”, concluyó. “Pero cuando regresa la enfermedad, se dan cuenta de que hay niños que se están enfermando de gravedad, y potencialmente muriendo en la propia comunidad, y todos dicen: ‘¡Caramba! ¡Mejor que vacunemos!’”.

En 2015, Ball trató a tres niños muy enfermos de sarampión. Después, su consultorio dejó de atender a pacientes no vacunados. “Tuvimos bebés expuestos en nuestra sala de espera”, dijo. “Tuvimos una propagación de la enfermedad en nuestra oficina, lo cual fue muy desagradable”.

Aunque dos niñas que eran sanas murieron de sarampión durante el brote de Texas, “la gente todavía no le teme a la enfermedad”, dijo Paul Offit, director del Centro de Educación sobre Vacunas del Hospital Infantil de Philadelphia, que ha atendido algunos casos.

Pero las muertes “han generado más angustia, según la cantidad de llamadas que recibo de padres que intentan vacunar a sus bebés de 4 y 6 meses”, contó Offit. Los niños generalmente reciben su primera vacuna contra el sarampión al año de edad, porque tiende a no producir inmunidad completa si se administra antes.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

6 months 6 days ago

Noticias En Español, Public Health, States, Trump Administration, vaccines

El temor a la deportación agrava los problemas de salud mental que enfrentan los trabajadores de los centros turísticos de Colorado

SILVERTHORNE, Colorado. — Cuando Adolfo Román García-Ramírez camina a casa por la noche después de su turno en un mercado en este pueblo montañoso del centro de Colorado, a veces se acuerda de su infancia en Nicaragua. Los adultos, recuerda, asustaban a los niños con cuentos de la “Mona Bruja”.

Si te adentras demasiado en la oscuridad, le decían, un gigantesco y monstruoso mono que vive en las sombras podría atraparte.

Ahora, cuando García-Ramírez mira por encima del hombro, no son los monos monstruosos a los que teme. Son los agentes del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas de Estados Unidos (ICE).

“Hay un miedo constante de que vayas caminando por la calle y se te cruce un vehículo”, dijo García-Ramírez, de 57 años. “Te dicen: ‘Somos de ICE; estás arrestado’, o ‘Muéstrame tus papeles’”.

Silverthorne, una pequeña ciudad entre las mecas del esquí de Breckenridge y Vail, ha sido el hogar de García-Ramírez durante los últimos dos años. Trabaja como cajero en un supermercado y comparte un apartamento de dos habitaciones con cuatro compañeros.

La ciudad de casi 5.000 habitantes ha sido un refugio acogedor para el exiliado político, quien fue liberado de prisión en 2023 después que el gobierno autoritario de Nicaragua negociara un acuerdo con el gobierno estadounidense para transferir a más de 200 presos políticos a Estados Unidos.

A los exiliados se les ofreció residencia temporal en Estados Unidos bajo un programa de libertad condicional humanitaria (conocido como parole humanitario) de la administración Biden.

Este permiso humanitario de dos años de García-Ramírez expiró en febrero, apenas unas semanas después que el presidente Donald Trump emitiera una orden ejecutiva para poner fin al programa que había permitido la residencia legal temporal en Estados Unidos a cientos de miles de cubanos, haitianos, nicaragüenses y venezolanos. Esto lo que lo ponía en riesgo de deportación.

A García-Ramírez se le retiró la ciudadanía nicaragüense al llegar a Estados Unidos. Hace poco más de un año, solicitó asilo político. Sigue esperando una entrevista.

“No puedo decir con seguridad que estoy tranquilo o que estoy bien en este momento”, dijo García-Ramírez. “Uno se siente inseguro, pero también incapaz de hacer algo para mejorar la situación”.

Vail y Breckenridge son mundialmente famosos por sus pistas de esquí, que atraen a millones de personas cada año. Pero la vida para la fuerza laboral del sector turístico que atiende a los centros turísticos de montaña de Colorado es menos glamorosa.

Los residentes de los pueblos montañosos de Colorado experimentan altas tasas de suicidio y adicciones, impulsadas en parte por las fluctuaciones estacionales de los ingresos, que pueden causar estrés a muchos trabajadores locales.

Las comunidades latinas, que constituyen una proporción significativa de la población residente permanente en estos pueblos de montaña, son particularmente vulnerables.

Una encuesta reciente reveló que más de 4 de cada 5 latinos encuestados en la región de la Ladera Occidental, donde se encuentran muchas de las comunidades rurales de estaciones de esquí del estado, expresaron una preocupación “extrema o muy grave” por el consumo de sustancias.

Esta cifra es significativamente mayor que en el condado rural de Morgan, en el este de Colorado, que también cuenta con una considerable población latina, y en Denver y Colorado Springs.

A nivel estatal, la preocupación por la salud mental ha resurgido entre los latinos en los últimos años, pasando de menos de la mitad que la consideraba un problema extremada o muy grave en 2020 a más de tres cuartas partes en 2023.

Tanto profesionales de salud como investigadores y miembros de la comunidad afirman que factores como las diferencias lingüísticas, el estigma cultural y las barreras socioeconómicas pueden exacerbar los problemas de salud mental y limitar el acceso a la atención médica.

“No recibes atención médica regular. Trabajas muchas horas, lo que probablemente significa que no puedes cuidar de tu propia salud”, dijo Asad L. Asad, profesor adjunto de sociología de la Universidad de Stanford. “Todos estos factores agravan el estrés que todos podríamos experimentar en la vida diaria”.

Si a esto le sumamos los altísimos costos de vida y la escasez de centros de salud mental en los destinos turísticos rurales de Colorado, el problema se agrava.

Ahora, las amenazas de la administración Trump de redadas migratorias y la inminente deportación de cualquier persona sin residencia legal en el país han disparado los niveles de estrés.

Según estiman defensores, en las comunidades cercanas a Vail, la gran mayoría de los residentes latinos no tienen papeles. Las comunidades cercanas a Vail y Breckenridge no han sufrido redadas migratorias, pero en el vecino condado de Routt, donde se encuentra Steamboat Springs, al menos tres personas con antecedentes penales han sido detenidas por el ICE, según informes de prensa.

Las publicaciones en redes sociales que afirman falsamente haber visto a oficiales del ICE merodeando cerca de sus hogares han alimentado aún más la preocupación.

Yirka Díaz Platt, trabajadora social bilingüe de Silverthorne, originaria de Perú, afirmó que el temor generalizado a la deportación ha llevado a muchos trabajadores y residentes latinos a refugiarse en las sombras.

Según trabajadores de salud y defensores locales, las personas han comenzado a cancelar reuniones presenciales y a evitar solicitar servicios gubernamentales que requieren el envío de datos personales. A principios de febrero, algunos residentes locales no se presentaron a trabajar como parte de una huelga nacional convocada por el “día sin inmigrantes”. Los empleadores se preguntan si perderán empleados valiosos por las deportaciones.

Algunos inmigrantes han dejado de conducir por temor a ser detenidos por la policía. Paige Baker-Braxton, directora de salud conductual ambulatoria del sistema de salud de Vail, comentó que ha observado una disminución en las visitas de pacientes hispanohablantes en los últimos meses.

“Intentan mantenerse en casa. No socializan mucho. Si vas al supermercado, ya no ves a mucha gente de nuestra comunidad”, dijo Platt. “Existe ese miedo de: ‘No, ahora mismo no confío en nadie'”.

Juana Amaya no es ajena a la resistencia para sobrevivir. Amaya emigró a la zona de Vail desde Honduras en 1983 como madre soltera de un niño de 3 años y otro de 6 meses. Lleva más de 40 años trabajando como limpiadora de casas en condominios y residencias de lujo en los alrededores de Vail, a veces trabajando hasta 16 horas al día. Con apenas tiempo para terminar el trabajo y cuidar de una familia en casa, comentó, a menudo les cuesta a los latinos de su comunidad admitir que el estrés ya es demasiado.

“No nos gusta hablar de cómo nos sentimos”, dijo, “así que no nos damos cuenta de que estamos lidiando con un problema de salud mental”.

El clima político actual solo ha empeorado las cosas.